“I’ll show you what horror means!” – Frederic March as Mr. Hyde

“I’ll show you what horror means!” – Frederic March as Mr. Hyde

Suggested listening: “The Monster Mash” by Bobby Pickett

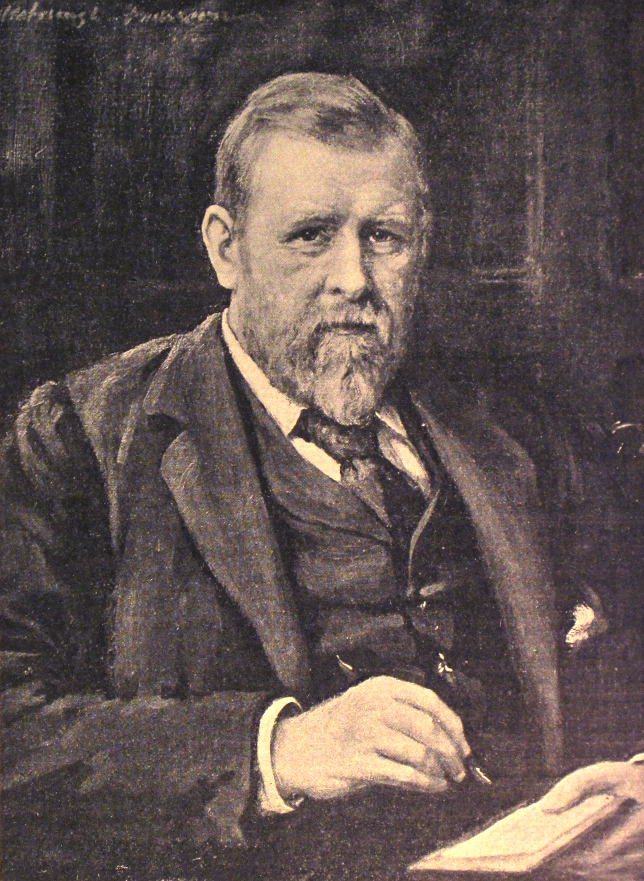

Although I was fortunate enough to meet and get to know David J. Skal many years later at a post-seminar reception at the Stag’s Head in central Dublin, my first introduction to him was through his seminal volume The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror (1993), which at the time was on the New Books shelf in my high school library. I’d told David on the night that I first met him the impact his book had had on me, a young horror fan, and how it repositioned and broadened my understanding of a genre I had always innately loved—he gave horror, from dusty old books to shimmering celluloid to the flickering cathode tube, the sort of validity that I needed at that point in my life. And as all the best horror surveys should do, David’s Monster Show sent me scurrying to the library, to video rental shelves, and to Madison’s once plentiful second-hand bookshops, with full permission to follow that excitement and seek out new horrors. As I write this, I have here my copy of The Monster Show, with its Edward Gorey cover, that David kindly inscribed for me that night in 2008: “That’s Monstertainment!”.

The next time I met David was in 2010, when he was a guest lecturer on the “Popular Literature” course at Trinity College Dublin. He was staying in a massive, newly built apartment complex on Ossory Road off North Strand. It had a spacious central courtyard that his flat faced onto. I recall David telling me during one of my visits there that he fancied himself perhaps the only inmate of the structure; at nightfall, he said, most of the other windows in the complex remained dark and vacant. Maybe. Dracula’s Castle—Recession Gothic.

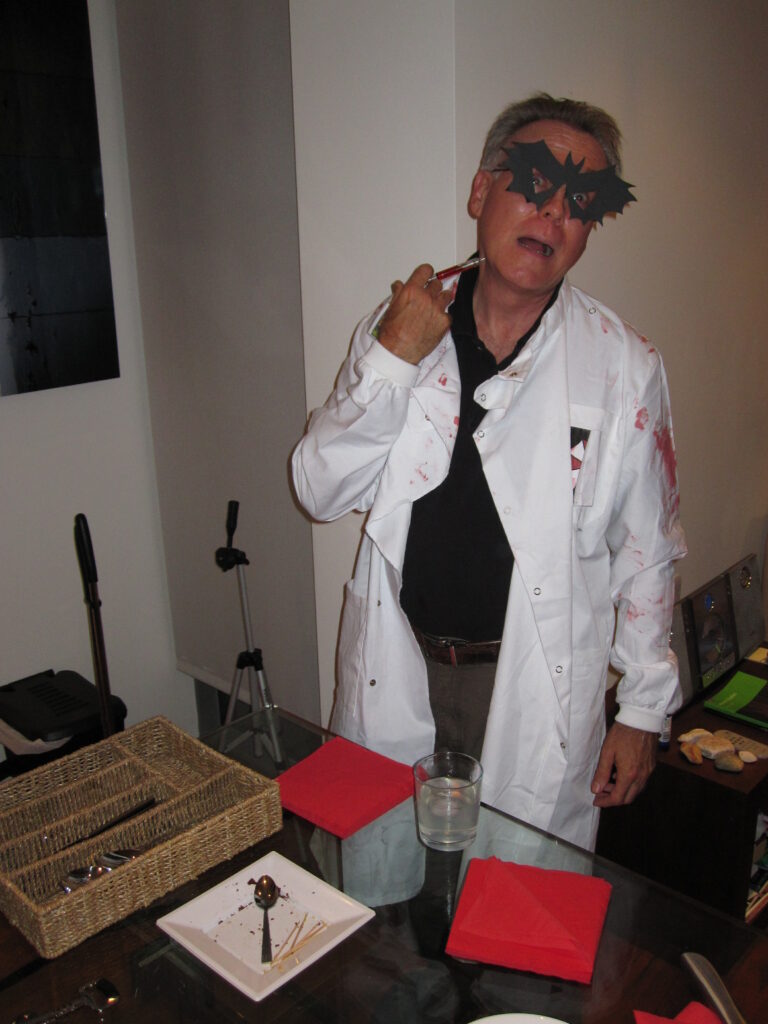

I was also invited to David’s Halloween party that year. David loved Halloween—of course he did! He wrote a book on it!—and the party was yet another manifestation of that lifelong condition since identified by medical experts as “Monster Kid”. It’s that fundamental impulse that drives some of us. You’ll know in your heart if you’re afflicted and will be familiar with the associated symptoms. David was absolutely stricken by it. He threw the party for his students and Trinity colleagues; I wasn’t affiliated with Trinity at all though, but I was glad to be welcomed. However, though not then a student, it is in large part due to David that I thought . . . perhaps I’d like to do a masters at Trinity. I enrolled the very next year.

I was also invited to David’s Halloween party that year. David loved Halloween—of course he did! He wrote a book on it!—and the party was yet another manifestation of that lifelong condition since identified by medical experts as “Monster Kid”. It’s that fundamental impulse that drives some of us. You’ll know in your heart if you’re afflicted and will be familiar with the associated symptoms. David was absolutely stricken by it. He threw the party for his students and Trinity colleagues; I wasn’t affiliated with Trinity at all though, but I was glad to be welcomed. However, though not then a student, it is in large part due to David that I thought . . . perhaps I’d like to do a masters at Trinity. I enrolled the very next year.

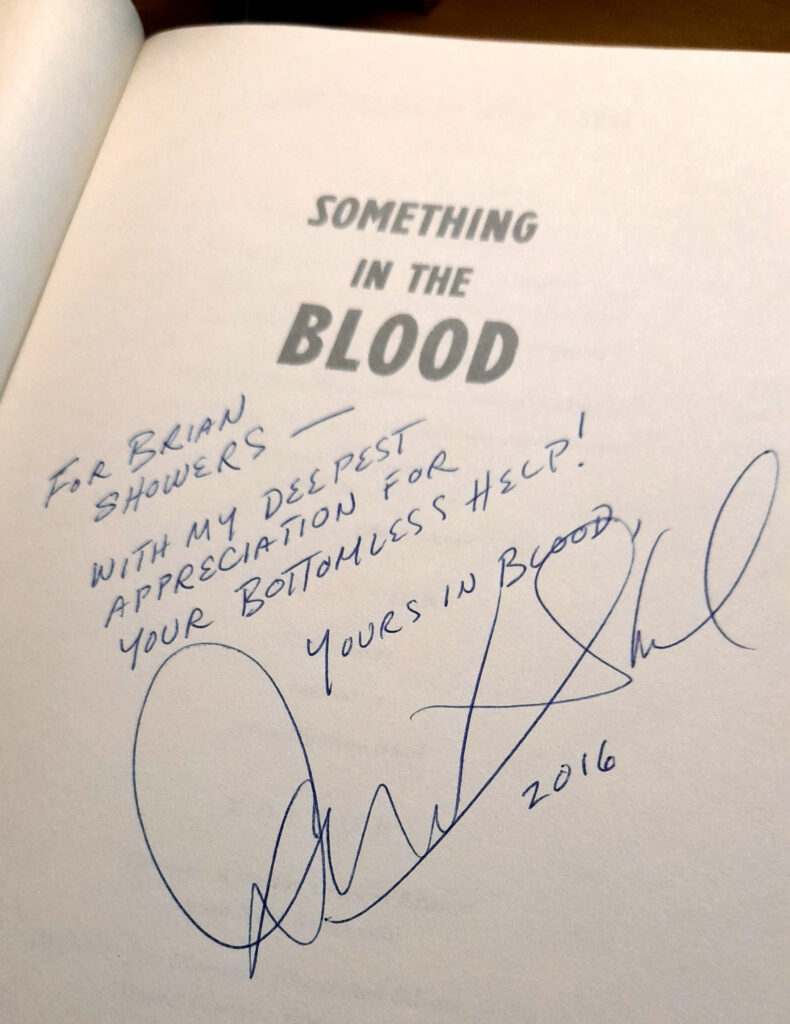

David spent a lot of time in Dublin over the subsequent years, occasionally staying with me. He was mainly doing research for his Stoker biography, Something in the Blood, which was published in 2016, so he had a reason for his many returns. But he’d made a lot of friends here in Dublin too—and he was always welcome, his visits felt more like homecomings. Often on his visits we would embark on long walks—and even longer conversations. We talked Irish Gothic and visited places associated with Stoker and Le Fanu, including some pretty obscure locales (the burial place of Stoker’s beloved childhood nurse, anyone?)

Like all good researchers, David asked a lot of questions. Not just of me, but in general. Sometimes I could answer, other times I wondered why I’d not asked the same such questions: “The multi-coloured Georgian doors of Dublin are celebrated now, but were they always painted like that?”. But this tendency to ask questions—in such a concise way, brilliantly free from the assumed—is a skill that I’ve noticed in all the best researchers and scholars. And that was David. He pursued until he was satisfied, until he knew his audience would be satisfied. David always knew his audience.

Another thing people seemed to notice about David when they met him, certainly I did, was his charming and urbane manner—and that voice! It was authoritative, but so warm and inviting. He wanted to share his passions with you. If you’ve seen the documentaries that he’s hosted or narrated, you’ll know his presence and what I mean. David was a natural storyteller, and I recall fondly listening to his memories, how he’d fished sheaves of old archives from a dumpster at Universal Studios, including, remarkably, correspondence from Stoker’s widow Florence—this was to become the backbone of his landmark book Hollywood Gothic (1990). David himself, in his dedication to and celebration of the silver screen, seemed to become a living repository for memories of an era, of the people he’d met, interviewed, and written about over his life, including David Manners, who played Harker in Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931). He also knew Carla Laemmle, Lupita Tovar, Ricou Browning (The Creature from the Black Lagoon was always my favourite!), Sarah Karloff, Raymond Huntley, and so many more. How wonderful that someone like David came along when he did, just as some of those memories of Old Hollywood, those connections to the distant past, were about to fade.

Another thing people seemed to notice about David when they met him, certainly I did, was his charming and urbane manner—and that voice! It was authoritative, but so warm and inviting. He wanted to share his passions with you. If you’ve seen the documentaries that he’s hosted or narrated, you’ll know his presence and what I mean. David was a natural storyteller, and I recall fondly listening to his memories, how he’d fished sheaves of old archives from a dumpster at Universal Studios, including, remarkably, correspondence from Stoker’s widow Florence—this was to become the backbone of his landmark book Hollywood Gothic (1990). David himself, in his dedication to and celebration of the silver screen, seemed to become a living repository for memories of an era, of the people he’d met, interviewed, and written about over his life, including David Manners, who played Harker in Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931). He also knew Carla Laemmle, Lupita Tovar, Ricou Browning (The Creature from the Black Lagoon was always my favourite!), Sarah Karloff, Raymond Huntley, and so many more. How wonderful that someone like David came along when he did, just as some of those memories of Old Hollywood, those connections to the distant past, were about to fade.

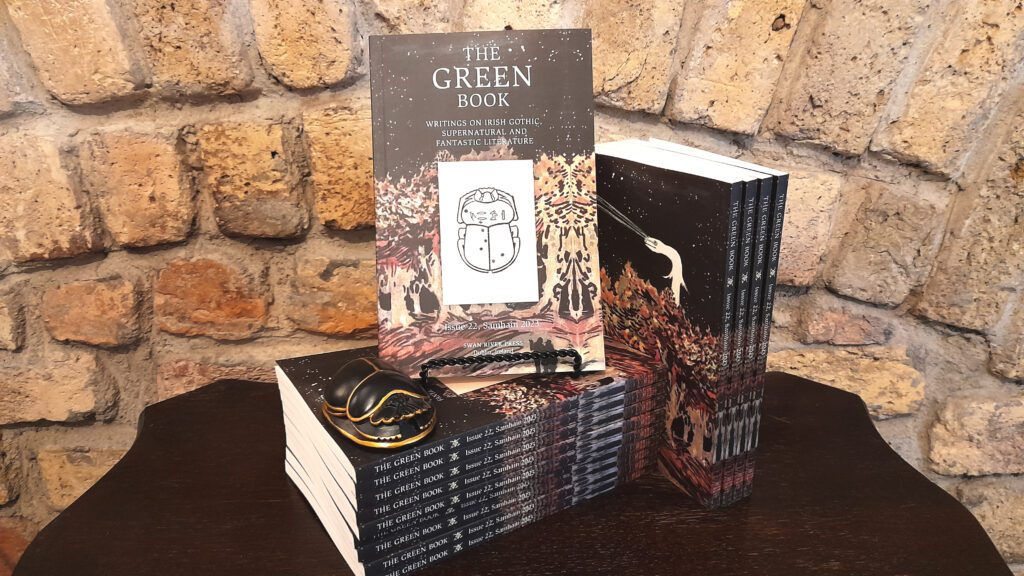

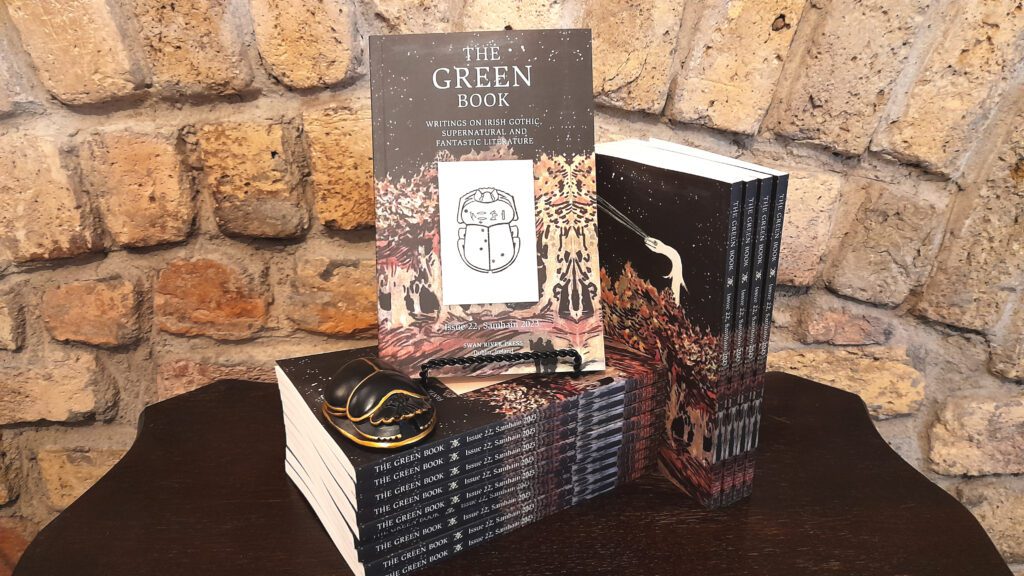

It was my absolute pleasure when David later asked me to help him with various bits of research as he worked on Something in the Blood. I’d often find myself in the National Library pursuing some scrap of information he was after. It was on one of these occasions that I unearthed, almost by chance, a previously unknown Stoker spook story called “Saved by a Ghost”. I excitedly emailed it to David, who responded with such enthusiasm; I reprinted the story for the first time in The Green Book 6, along with commentary by David. Similarly, David wrote an article for The Green Book 4 when I’d located the only known manuscript copy of Lord Longford’s stage adaptation of Carmilla (1932). “The Lady Who Munched—How Carmilla Stormed the Stage” is a sort of Hollywood Gothic-like examination of Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” and it’s trajectory on the stage. More excited emails, of course. Anyway, it’s hard to describe the almost Jamesian thrill of such discoveries, suffice to say I’m so happy to have been able to share these moments with David.

One final memory, perhaps my favourite: David was staying with me in July 2012 on one of his return trips to Dublin. He had asked if I would take publicity photos for him, photos he has since used for the past decade or so. I’m no professional, but David was, and he knew exactly what he wanted, so I obliged. We trounced around Mount Jerome Cemetery in south Dublin looking for perfect backdrops; they were plentiful. David posed and pulled faces for me while I inexpertly snapped away. Rain threatened, but David wanted to use an umbrella as a prop anyway. When Something in the Blood was published, I felt delighted to read David’s warm inscription and acknowledgement note—but also on the jacket’s rear flap was produced one of the photos from the day we shared in Mount Jerome. Before we’d left the house that morning, David asked me, “Do you have a tie I could borrow?” I did. Now, whenever I see those photos—and they’re reproduced a lot, especially now—I feel a special connection. That tie always makes me laugh and remember. I still have it too.

One final memory, perhaps my favourite: David was staying with me in July 2012 on one of his return trips to Dublin. He had asked if I would take publicity photos for him, photos he has since used for the past decade or so. I’m no professional, but David was, and he knew exactly what he wanted, so I obliged. We trounced around Mount Jerome Cemetery in south Dublin looking for perfect backdrops; they were plentiful. David posed and pulled faces for me while I inexpertly snapped away. Rain threatened, but David wanted to use an umbrella as a prop anyway. When Something in the Blood was published, I felt delighted to read David’s warm inscription and acknowledgement note—but also on the jacket’s rear flap was produced one of the photos from the day we shared in Mount Jerome. Before we’d left the house that morning, David asked me, “Do you have a tie I could borrow?” I did. Now, whenever I see those photos—and they’re reproduced a lot, especially now—I feel a special connection. That tie always makes me laugh and remember. I still have it too.

There is much to be said on the impact of David’s work: be it through books like The Monster Show, Dark Carnival, Death Makes a Holiday, or Screams of Reason; his many documentaries for Universal Studios; or his wonderful championing of the Spanish-language film version of Dracula, shot simultaneously alongside Tod Browning’s classic. I’ll leave that commentary to others. As for me, I just wanted to set down this morning just a few of my own memories before they too, like all things, eventually fade away. I will always be grateful for the opportunity to spend time and forge a friendship with someone who I admire so much. It’s often said that you should never meet your heroes. I’ve said before, and I still think it’s true: Meet your heroes. Thank you for the inspiration. I’ll miss you, David. Yours in blood . . .

Brian J. Showers

Æon House, Dublin

12 January 2024

“Editor’s Note”

“Editor’s Note” Douglas A. Anderson submitted a year ago an uncollected piece entitled “Black Spirits and White” by Henry Irving—or perhaps not? As Anderson conjectures in his brief note introducing the tale, there is a possibility that Stoker himself might have penned the piece (Mystery #2). Alas, we will likely never learn the answer, however you’re welcome to draw your own conclusion.

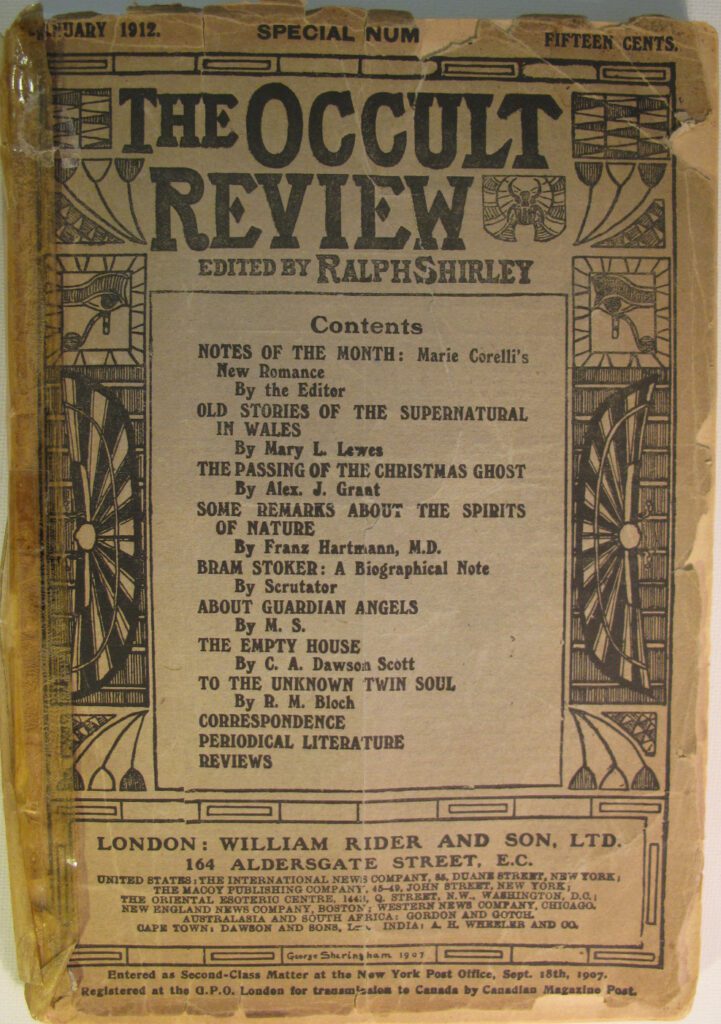

Douglas A. Anderson submitted a year ago an uncollected piece entitled “Black Spirits and White” by Henry Irving—or perhaps not? As Anderson conjectures in his brief note introducing the tale, there is a possibility that Stoker himself might have penned the piece (Mystery #2). Alas, we will likely never learn the answer, however you’re welcome to draw your own conclusion. I hope you’ll allow me a further indulgence, but I’m running one of my own articles in this issue—an essay with which readers of the late, lamented journal Wormwood might already be familiar. In “Bram Stoker and Another Dracula”, I discuss whether or not Stoker ever intended to write a sequel to Dracula (Mystery #3). It’s a question that fascinates me, and I think I’ve come up with a pretty good answer—but we can never know for sure. This essay was inspired by a paraphrased “interview” with Stoker that appeared in an issue of The Occult Review, just months before his passing in April 1912. In this piece, Mr. Stoker divulges some curious titbits, which I make use of in my own essay. I won’t spoil the surprise, but I thought it worth reprinting this interview in its entirety as well.

I hope you’ll allow me a further indulgence, but I’m running one of my own articles in this issue—an essay with which readers of the late, lamented journal Wormwood might already be familiar. In “Bram Stoker and Another Dracula”, I discuss whether or not Stoker ever intended to write a sequel to Dracula (Mystery #3). It’s a question that fascinates me, and I think I’ve come up with a pretty good answer—but we can never know for sure. This essay was inspired by a paraphrased “interview” with Stoker that appeared in an issue of The Occult Review, just months before his passing in April 1912. In this piece, Mr. Stoker divulges some curious titbits, which I make use of in my own essay. I won’t spoil the surprise, but I thought it worth reprinting this interview in its entirety as well.

EDITOR’S NOTE

EDITOR’S NOTE

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

Novels and Collections

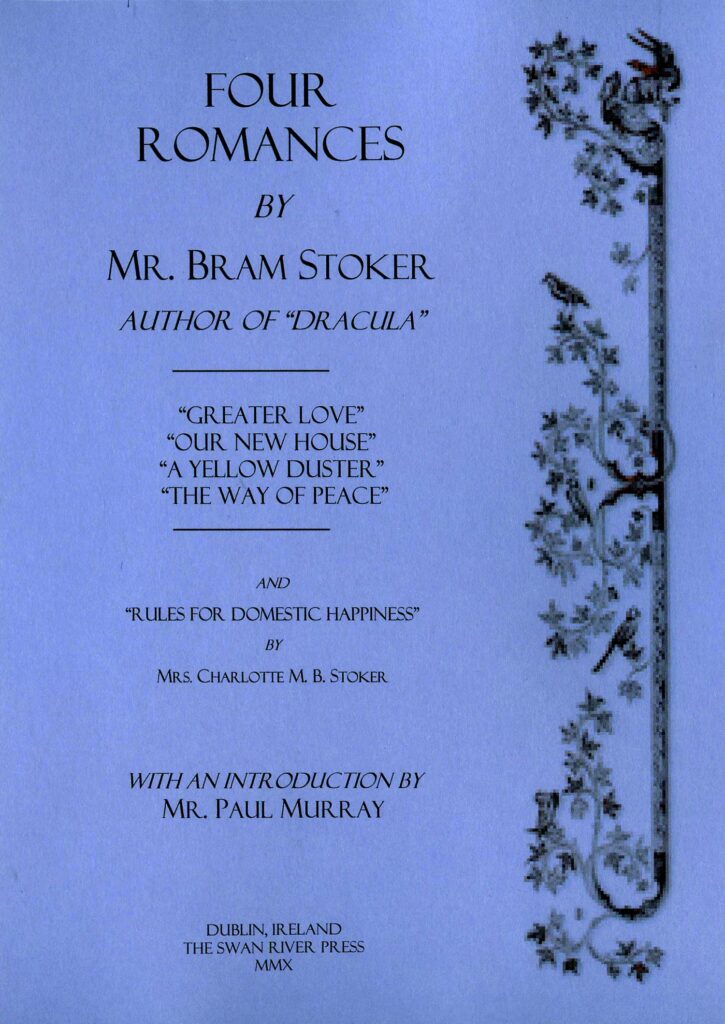

Novels and Collections Swan River Press has a number of Bram Stoker publications available, including the limited edition

Swan River Press has a number of Bram Stoker publications available, including the limited edition

“Dracula’s Guest”, atmospheric and other-worldly in execution, has caused over a century of head scratching in Stoker scholarship circles: How exactly does this excised episode fit into Dracula? What accounts for the inconsistencies between the story and the novel? Did a ghost writer contribute to “Dracula’s Guest” in whole or in part? These questions have been explored sufficiently elsewhere, and there is little point in discussing them again here.

“Dracula’s Guest”, atmospheric and other-worldly in execution, has caused over a century of head scratching in Stoker scholarship circles: How exactly does this excised episode fit into Dracula? What accounts for the inconsistencies between the story and the novel? Did a ghost writer contribute to “Dracula’s Guest” in whole or in part? These questions have been explored sufficiently elsewhere, and there is little point in discussing them again here. While I would not presume to claim that Old Hoggen and Other Adventures is a long-lost classic by Bram Stoker, I do hope that it stands as a tantalising possibility, one of the other two collections Stoker was planning in his final years. Rather, the book you now hold in your hands I hope will be read as the collection that might have been.

While I would not presume to claim that Old Hoggen and Other Adventures is a long-lost classic by Bram Stoker, I do hope that it stands as a tantalising possibility, one of the other two collections Stoker was planning in his final years. Rather, the book you now hold in your hands I hope will be read as the collection that might have been.

A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier

A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier