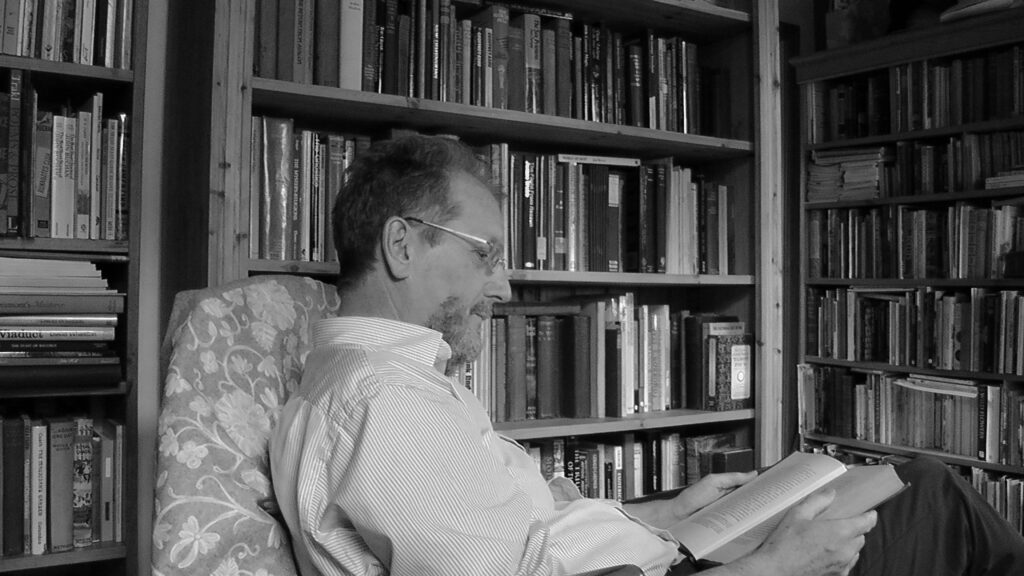

John Kenny in Conversation with Mark Valentine about Mark’s new collection Lost Estates.

John Kenny in Conversation with Mark Valentine about Mark’s new collection Lost Estates.

Mark Valentine is the author of several volumes of short stories including The Collected Connoisseur (Tartarus Press 2010) and Secret Europe (Ex Occidente Press 2012), both shared titles with John Howard. He has also written a biography of Arthur Machen (Seren 1990); and Time, a Falconer (Tartarus Press 2011), a study of the diplomat and fantasist “Sarban”. His books with Swan River Press include Selected Stories (2012) and Seventeen Stories (2013), both collections of his short fiction, and The Far Tower (2019), an original anthology of stories in celebration of W. B. Yeats.

John Kenny: Your previous collections published by Swan River Press focused on Middle Europe between the wars. This time out the focus is more on aspects of folk horror. There exists a strong tradition of folk horror that’s deeply rooted in the English rural landscape. Why do you think that is? And can you tell me who your inspirations are in this regard?

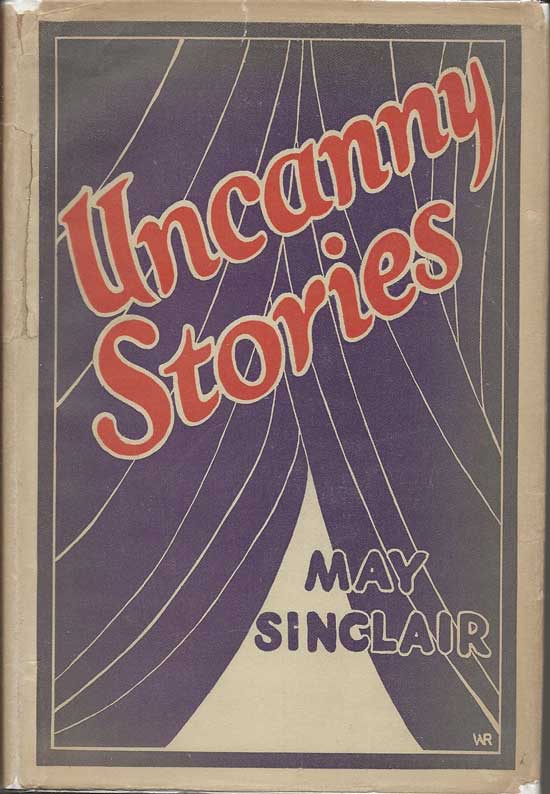

Mark Valentine: I’d like to plead “not guilty” to “folk horror”! I prefer a couple of terms I came upon recently in contemporary 1923 reviews of Uncanny Stories by May Sinclair and Visible and Invisible by E. F. Benson. The publisher, presumably with these authors’ agreement, called them “borderland” and “otherworld” stories, evidently terms then in use and well understood for occult and supernatural fiction. I think they do convey better the sense that can sometimes be felt in certain places of being close to a different realm. I’ve certainly had that experience several times and I appreciate in particular the work of writers who have also tried to express this sense of the numinous, such as Arthur Machen, Mary Butts, Forrest Reid, Jocelyn Brooke, John Cowper Powys and quite a few others in the field. For me, this was also bound up with my discovery in my late teens and early twenties of ancient mysteries books and journals, such as Mysterious Britain by Janet & Colin Bord and its sequels, which made exploring antiquities and remote landscapes seem exciting and strange, as if the world of Machen and these similar writers still existed.

Mark Valentine: I’d like to plead “not guilty” to “folk horror”! I prefer a couple of terms I came upon recently in contemporary 1923 reviews of Uncanny Stories by May Sinclair and Visible and Invisible by E. F. Benson. The publisher, presumably with these authors’ agreement, called them “borderland” and “otherworld” stories, evidently terms then in use and well understood for occult and supernatural fiction. I think they do convey better the sense that can sometimes be felt in certain places of being close to a different realm. I’ve certainly had that experience several times and I appreciate in particular the work of writers who have also tried to express this sense of the numinous, such as Arthur Machen, Mary Butts, Forrest Reid, Jocelyn Brooke, John Cowper Powys and quite a few others in the field. For me, this was also bound up with my discovery in my late teens and early twenties of ancient mysteries books and journals, such as Mysterious Britain by Janet & Colin Bord and its sequels, which made exploring antiquities and remote landscapes seem exciting and strange, as if the world of Machen and these similar writers still existed.

JK: I really like that term “borderland”. Folk horror does seem to be largely connected to rural settings, whereas a couple of your stories in Lost Estates take place in cities: “And maybe the parakeet was correct” and “The End of Alpha Street”. I do think city streets and houses can accrete this sense of the numinous you’ve referred to. I’m thinking of some of Peter Ackroyd’s work, such as Hawksmoor, and that of Iain Sinclair and the whole concept of psychogeography. Is this a concept you think has validity?

MV: Yes, I admire the work of Iain Sinclair too and particularly the way he uses modernist literary techniques in his prose: the supernatural fiction field can sometimes seem a bit fusty and it’s good to see a more contemporary style: another example of a more radical approach would be M. John Harrison. And in fact Machen is now seen as a precursor of psychogeography, with his interest in wandering the back-streets and lonely quarters of London, as seen in The London Adventure, or, The Art of Wandering and with his flâneur Mr. Dyson. My friend and colleague John Howard does this to fine effect too, in his London stories. My understanding of the original concept of psychogeography is that it involves “aimless wandering”, the aimlessness being vital: ambling around just for the sake of it and seeing what transpires. I can see that this might lead to a heightened receptivity, where chance encounters and signs begin to seem significant: again, an approach Machen uses in his stories.

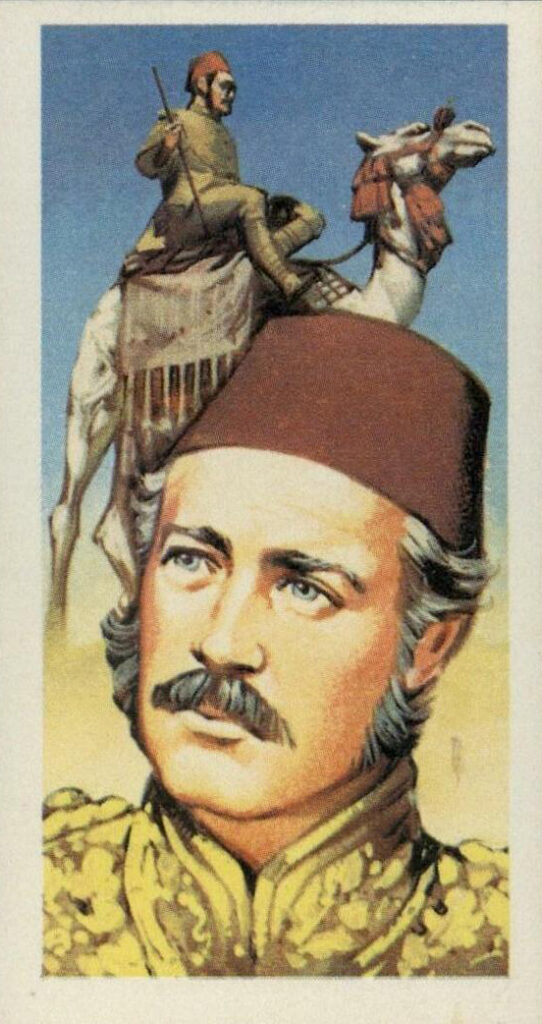

JK: There is certainly a sense of aimless wandering in “The House of Flame”, where the main character takes to the London streets, although he is in search of a kind of spiritual awakening. The story centres around the death in 1885 of Charles George Gordon, who is also referenced in another story in Lost Estates. What drew you to the story of Gordon of Khartoum?

JK: There is certainly a sense of aimless wandering in “The House of Flame”, where the main character takes to the London streets, although he is in search of a kind of spiritual awakening. The story centres around the death in 1885 of Charles George Gordon, who is also referenced in another story in Lost Estates. What drew you to the story of Gordon of Khartoum?

MV: Well, in my childhood there was a series of colourful cards of Famous People given away with boxes of Brooke Bond tea. I was very interested in history and I enjoyed collecting these. The two that appealed to me most were not, as perhaps they should have been, social reformers and scientists, but two enigmatic soldiers: General Gordon and Lawrence of Arabia. No doubt it was because they seemed more mysterious. Later, I read in one of Machen’s autobiographical volumes his recollection of bringing the news of the fall of Khartoum to his father in the rectory at Llandewi, using his schoolboy Greek. This vignette stuck in my memory, and so when I was asked to contribute to a Machen-themed anthology I imagined a version of the youthful Machen and what the figure of Gordon might have meant to him.

JK: While Gordon couldn’t be considered a social reformer, he was actively involved in suppressing the slave trade in Sudan while he was there. I note that many of your stories use as a jumping off point an actual historical event, as in “The Fifth Moon”, which looks at the disappearance of King John’s treasure in 1216. Do you find that having an actual event at the heart of a story lends credibility or is it more a case of your interest in history acting as inspiration?

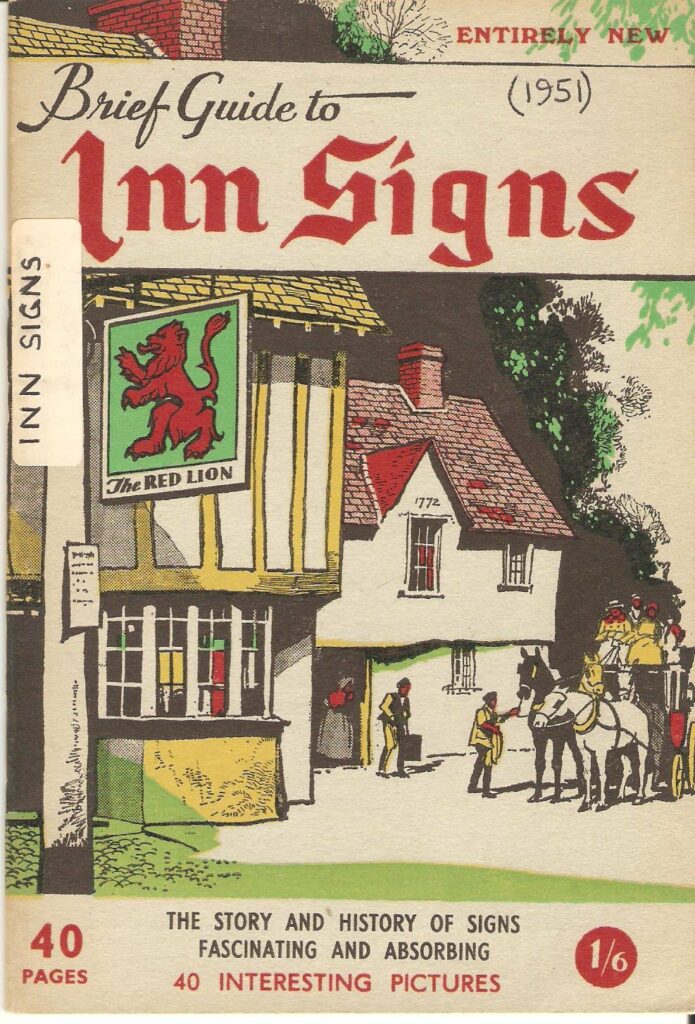

MV: I am interested in the way that history, legend, and literature interweave. I’ve been following the latest historical thinking on the figure of Arthur, which is now highly sceptical about not only any factual basis for such a king or warlord, but even the whole Britons vs Saxons story. It just isn’t supported by current archaeology or newly available genetic studies. Probably that will need to be refined further as research and analysis continues: the discipline of history itself is always changing. In the case of King John’s treasure, I was already familiar with the lonely landscape around North Norfolk and South Lincolnshire where the loss occurred and so enjoyed setting the story there, and it is an enduring mystery which still fascinates people today: treasure hunts are always thrilling. I also relished studying the various accounts of the incident and trying to trace exactly what was said at the time and how that has been changed through the centuries, making the story more alluring and romantic. In my own researches, for example on legends of the last wolf in England and on the origins of inns signs, I’ve tried to go back to the very earliest sources. They often tell a quite different story to the current one, and that is the case with King John’s treasure too. Then, of course, the imagination comes into play and I began to wonder just what was lost, and what might survive.

JK: It is a fascinating piece of history, yes. It’s clear that not a little research goes in to many of your stories and that’s part of what makes them so compelling. Your mention of inn signs, for example, which is the main subject of “The Understanding of the Signs” and is also an element in “Worse Things Than Serpents”; I’m curious to know if the specifics of the signs mentioned are true. And do the books listed exist?

JK: It is a fascinating piece of history, yes. It’s clear that not a little research goes in to many of your stories and that’s part of what makes them so compelling. Your mention of inn signs, for example, which is the main subject of “The Understanding of the Signs” and is also an element in “Worse Things Than Serpents”; I’m curious to know if the specifics of the signs mentioned are true. And do the books listed exist?

MV: Yes, all of the inn sign books mentioned in that story are real and almost all of the books the narrator finds in “Worse Things Than Serpents” too. Inn signs have interested me since I was young too: on family journeys I would write down the names of all those we passed, and later started with a friend an inn signs newsletter. When I came back to studying them, I found that the usual explanations for the most popular signs simply don’t hold up. They can often be traced to a stout Victorian study but even there were often advanced tentatively. It’s another example of stories repeated through the ages that only have the thinnest basis. But when you do start to ask what is the origin of the signs, you uncover a much richer and more varied set of possibilities. Also, they seem part of what I have called “folk heraldry”, the popular enjoyment of strange beasts and monsters as local symbols.

JK: Which feeds very much into the history of an area or locality and how people interact or become part of that landscape. I’m thinking of “Fortunes Told: Fresh Samphire” and its possible companion piece “The Readers of the Sands” (by virtue of the fact that they both feature a character named Crabbe). The sense of place in your stories is very well realised. Have you visited all the places in which your stories are set?

MV: Some of the places I know very well but others I haven’t visited at all. But when I’m writing a story I like to have a clear idea of the setting, by studying maps, looking at old postcards, reading old walking guides. I try to imagine just what the character might see, hear and smell in that particular season. What would their journey there be like, what would they do when they got there, what route would they take to their destination? In “A Chess Game at Michaelmas”, for example, the custom in question is a perfectly genuine one and it belongs to a house located just where I describe, though I have adapted it a bit fictionally. So in writing the story I worked out where was then the nearest railway station, and what would be the way the narrator gets from there to the house on foot. As it happens, that would take him past some ancient stones with interesting lore, also genuine, though again adapted slightly.

JK: “A Chess Game at Michaelmas” is one of my favourites in this collection. And the journey to the house is as much an integral part of the story as the custom in question. As is your reference to yew trees in this and a couple of other stories in Lost Estates. Is there a particular significance to these references?

JK: “A Chess Game at Michaelmas” is one of my favourites in this collection. And the journey to the house is as much an integral part of the story as the custom in question. As is your reference to yew trees in this and a couple of other stories in Lost Estates. Is there a particular significance to these references?

MV: Yes, I have a fondness for slightly overgrown or semi-wild gardens, that point where the art of the gardener has been reclaimed and reshaped somewhat by nature. Topiary, often with yew trees, is already beguiling because of its figuring into strange shapes and when it’s a bit neglected it looks wilder still. I like that blend of artistry, pageantry and yet melancholy they seem to convey.

JK: With the demise of Wormwood, the magazine of fantasy, the supernatural and decadent literature, which you edited, is the primary focus for you now on your own writing? And is there a novel in you or is the short form your first love?

MV: Well, I still contribute to the Wormwoodiana shared blog, where we try to cover similar books and authors to those we might have featured in the journal. I’m usually following up discoveries from my book-collecting expeditions, which may lead to further essays. I even dream about browsing in bookshops, and sometimes remember titles from the dream shelves.

I’m currently working on an anthology of essays about Malcolm Lowry and his use of magic and myth, which I think are quite important themes in his books. As to fiction, I’ve enjoyed in more recent years writing longer stories (typically 12,000-15,000 words) and would like to try a few more of those, but I don’t think I have a novel lurking anywhere. I like the short story form and I think it still has a lot of possibilities.

Buy a copy of Lost Estates.

If you’d like, you can read John Kenny’s full review of Lost Estates.

Similarly, the Dark Stranger introduces Jenny to fairy rings in the grass and tells her how the Little People made them by dancing in the moonlight. He shows her a big yellow toad under a boulder. He reveals deadly nightshade, witches’ bane, hemlock, poisonous mushrooms. He spins her tales of tree-witches and wood-spirits, nymphs and dryads, fauns and satyrs. She also comes to learn that she might be descended from two sisters burned at the stake many centuries ago.

Similarly, the Dark Stranger introduces Jenny to fairy rings in the grass and tells her how the Little People made them by dancing in the moonlight. He shows her a big yellow toad under a boulder. He reveals deadly nightshade, witches’ bane, hemlock, poisonous mushrooms. He spins her tales of tree-witches and wood-spirits, nymphs and dryads, fauns and satyrs. She also comes to learn that she might be descended from two sisters burned at the stake many centuries ago.

Conducted by Michael Dirda, © February 2018

Conducted by Michael Dirda, © February 2018 Machen is very different. He is a magician with words. His love of the countryside and his fascination for the city both resonated with me when I left rural Sussex aged eighteen for the city of Sheffield, and his work still moves me profoundly. He has his faults as a writer (characterisation, mainly), but this is more than made up for by the depth of his vision and the power of his lyricism. There is an inherent humanity in Machen that I don’t find in Aickman.

Machen is very different. He is a magician with words. His love of the countryside and his fascination for the city both resonated with me when I left rural Sussex aged eighteen for the city of Sheffield, and his work still moves me profoundly. He has his faults as a writer (characterisation, mainly), but this is more than made up for by the depth of his vision and the power of his lyricism. There is an inherent humanity in Machen that I don’t find in Aickman.