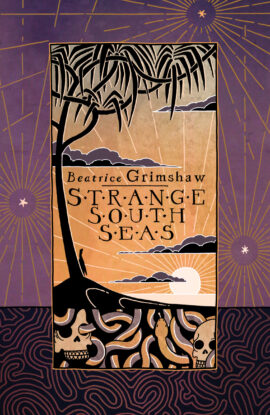

Strange South Seas

Beatrice Grimshaw

Availability: Pre-order – Hardback

This book will ship in late February.

“There are places in the Pacific almost as far away as another star.”

In the magical and beautiful islands of the South Seas, belief in the supernatural can mean the difference between life and death. Beatrice Grimshaw, though born and raised in Ireland, lived and breathed the culture of the islands for most of her adult life. In these stories, she conjures the Pacific’s darker side, where sorcerers practice their ancient craft, where enchanting forests ensnare the unwary, where ghosts linger for thousands of years, and where beauty often casts a sinister shadow. Strange South Seas is the first collection gathering together a career-spanning selection of Grimshaw’s spectral and speculative tales depicting terrains at the edge of the world and beyond.

Please note: Some stories in this collection include colonial attitudes and racist language. The stories are reprinted as they originally appeared.

- Part of our Strange Stories by Irish Women series

- More on Beatrice Grimshaw can be found in various issues of The Green Book

Hardback edition limited to 350 copies.

Selected and introduced by Mike Ashley

Cover art by Brian Coldrick

ISBN: 978-1-78380-055-1 (hbk)

“Queen of the South Seas” – Mike Ashley

“Through the Back Door”

“Lost Wings”

“The Long, Long Day”

“The Singing Ghost”

“Cabin No. 9”

“The Blanket Fiend”

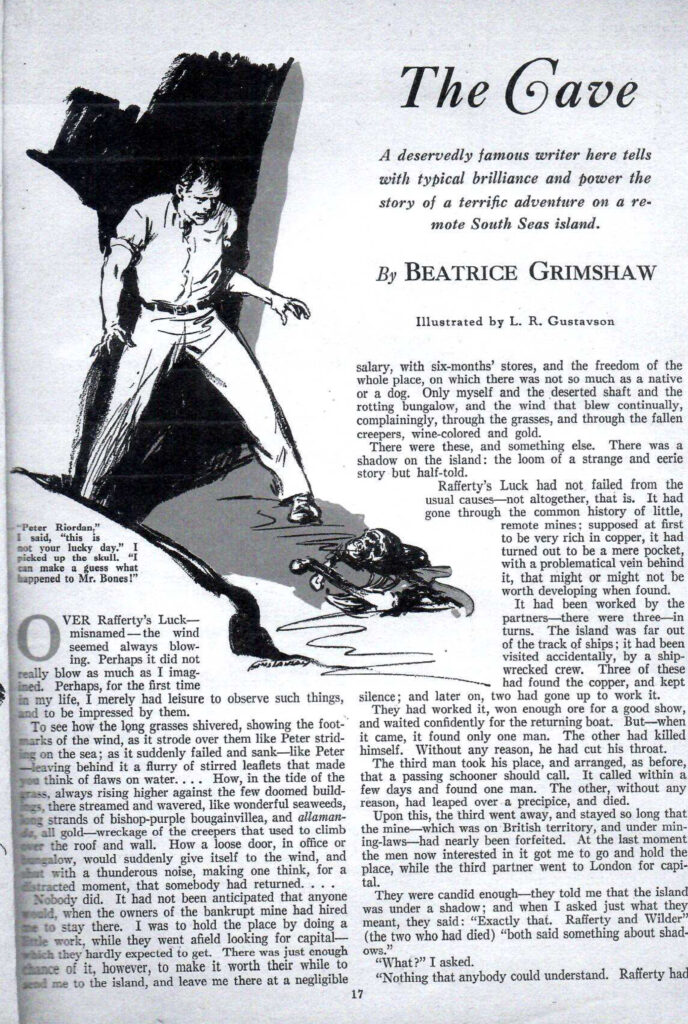

“The Cave”

“The Devil’s Smithy”

“The Flaming Sword”

“The Forest of Lost Men”

“A Friend in Ghostland”

“Sources”

“About the Author”

“About the Editor”

Beatrice Grimshaw

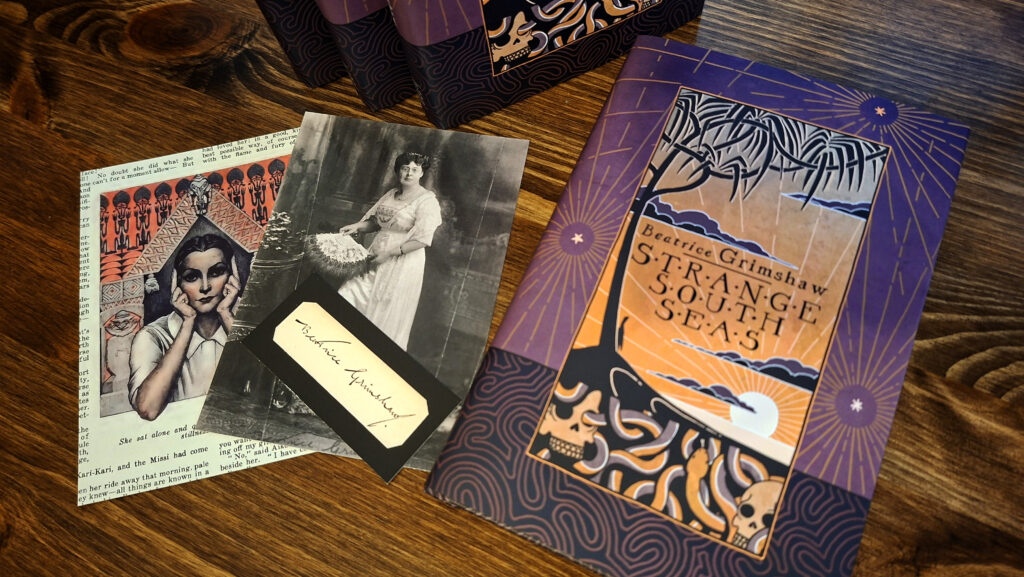

Beatrice Grimshaw was born in Dunmurry, Co. Antrim in 1870. Though raised in Ireland, and educated in France, Grimshaw is primarily associated with Australia and the South Seas, which she wrote about in her fiction and travel journalism. In 1904 Grimshaw was commissioned by London’s Daily Graphic to report on the Pacific islands, around which she purportedly sailed her own cutter, never to return to Europe again. After living much of her life in New Guinea, Grimshaw retired to New South Wales, where she died in 1953.

- More on Beatrice Grimshaw can be found in various issues of The Green Book

Strange South Seas by Beatrice Grimshaw; cover art by Brian Coldrick; jacket design by Meggan Kehrli; selected and introduced by Mike Ashley; edited by Brian J. Showers and Jim Rockhill; copyedited by John Kenny; typeset by Steve J. Shaw.

First Hardback Edition: Published on February 2026; limited to 350 copies, the first 100 of which are embossed and hand-numbered; dust jacketed; illustrated cloth-printed boards; endpapers (WBN502 Fawn); xiii + 249 pages; lithographically printed on 80 gsm cream paper; sewn binding; head- and tail-bands (Winterband 704 cream); issued with two postcards and one signature card; printed by CPI Antony Rowe; ISBN: 978-1-78380-055-1.

“Adventure in the South Seas”

“Adventure in the South Seas”

Conducted by John Kenny © January 2026

Mike Ashley is a major enthusiast and collector of a wide range of popular fiction, including science fiction, fantasy, supernatural, and crime fiction. He has compiled or edited well over one hundred anthologies of short stories across the whole spectrum of genre fiction and has written a biography of Algernon Blackwood and a five-volume history of science fiction magazines. His Age of the Storytellers (British Library 2005) explores the British popular fiction magazines from the 1880s to the 1940s and he received the Pilgrim Award for Lifetime Achievement in science fiction scholarship in 2002 and the Edgar Award for the Mammoth Encyclopedia of Modern Crime Fiction (Robinson Publishing 2002) in 2003.

John Kenny: Tell us a little about Beatrice Grimshaw. It’s quite an achievement for a woman from Northern Ireland to fetch up in the Pacific Islands as a travel writer in the early 1900s.

Mike Ashley: It’s one of the factors that appealed to me about Grimshaw. She was clearly an adventurer, and one with a vivid imagination. She was born in Northern Ireland, where her great-grandparents had relocated from Lancashire. They were mill owners there a century before. I imagine her as quite a wilful child, with an evident wanderlust. She was an ardent cyclist in her youth, cycling for miles and miles, and the moment she could leave home—she did. She discovered she could write about her travels for the magazines and for the shipping lines’ own magazines so once she could earn her keep she travelled on the big ocean-going liners writing about where they travelled. She fell in love with the South Seas and eventually settled in what is now Papua New Guinea, and was the first white women to venture inland along the Fly and Sepik rivers.

JK: That’s quite daring, certainly back then. And was it her travels that inspired her to write fiction? Or was she doing so before she left these shores?

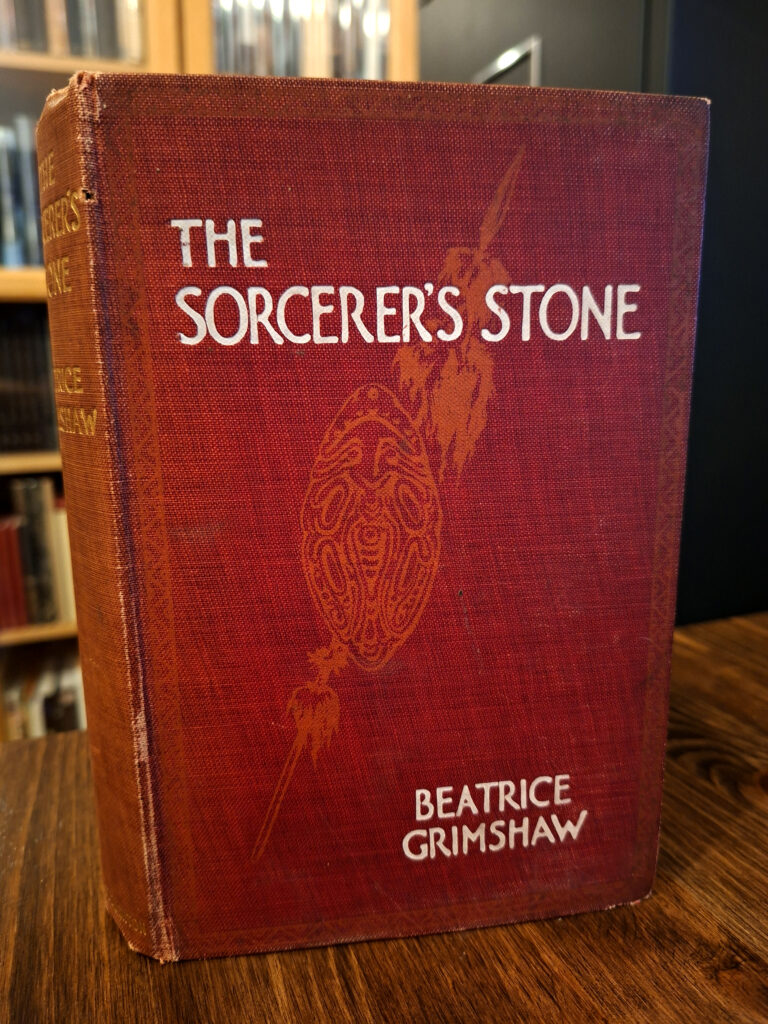

MA: She had written some fiction, but not much. Her writings were mostly journalism, reviews, and articles for various Irish magazines and newspapers. But once she reached the South Seas, travelling around the many islands before settling down, she was inspired, particularly by the idea of an adventurous woman amongst the travellers, settlers, and the indigenous peoples on those islands—Samoa, Fiji, the New Hebrides, Papua, and so on. She had immediate success with her first South Seas novel, Vaiti of the Islands, which was serialised in the Sydney Morning Herald and the Saturday Evening Post in 1906, and was picked up by the British Pearson’s Magazine in 1907. It concerns a young woman who becomes a “native queen”.

JK: I wonder if there was an element of wish fulfilment with regard to becoming a “native queen”. What do you think it was that fascinated Grimshaw about the indigenous islanders of the South Sea?

JK: I wonder if there was an element of wish fulfilment with regard to becoming a “native queen”. What do you think it was that fascinated Grimshaw about the indigenous islanders of the South Sea?

MA: I’m not sure it was wish fulfilment as much as day-dreaming or that sense of wonder we all have. She became fascinated by the indigenous people, and though in her writings she betrayed the typical racist attitudes of the day, she also seems to have had a lot of respect for the islanders and their various beliefs. She came to believe that the islanders had an entirely different outlook to western civilisation, freed, as it was, from our class structure and constrictive histories—especially in Catholic Ireland. The islanders were much closer to the land and nature, and though she never witnessed anything that was overtly supernatural, she could sense their abilities to understand the natural world in a way that she couldn’t, and it could easily be interpreted as a supernatural power. That affinity with the natural world comes through in many of her stories, often to the detriment of the white settlers.

JK: Yes, that racism is evident in a few of the stories in Strange South Seas, particularly “The Long, Long Day” and “The Blanket Fiend”. And “The Devil’s Smithy” revolves around the work of a Christian Mission in the Sheba Islands. What were Grimshaw’s views regarding the concept of “civilising natives” that was prevalent at the time?

MA: Racism in any form is abhorrent to me, but it’s not something you can simply hide, because it was so prevalent during the period Grimshaw was writing. I find myself torn between including the various comments or deleting them, as that borders on censorship. My general view is that such comments should stay. To my mind if a story contains no redeeming values, then I’d rather not reprint the story at all, but if the racist comments are limited then I’d rather run them as is than attempt to change them. And she certainly did not support the view of “civilising natives”. Whilst some of her comments are racist, she also had a lot of respect for the indigenous islanders and believed their culture and beliefs should be preserved.

JK: I do think it’s possible to read something that’s very much of its time and enjoy it while not condoning abhorrent aspects of the story. This is certainly the case with “The Blanket Fiend”, perhaps the most swashbuckling story in Strange South Seas, and reminiscent of H. Rider Haggard. Would she have been familiar with his work?

MA: Grimshaw never said much about her own reading habits, leastways not in the books I have. I do have her “memoirs”, such as they are, which are really about her travels, but for the moment I can’t lay my hands on it. But in general I’d say it’s pretty certain she would have read something by Haggard, because he was someone almost everyone read at the time. I know she was well read but I don’t know how much that influenced her writing. I do know she was influenced by the Australian writer Louis Becke (1855-1913), who was well steeped in the magic of the Pacific.

MA: Grimshaw never said much about her own reading habits, leastways not in the books I have. I do have her “memoirs”, such as they are, which are really about her travels, but for the moment I can’t lay my hands on it. But in general I’d say it’s pretty certain she would have read something by Haggard, because he was someone almost everyone read at the time. I know she was well read but I don’t know how much that influenced her writing. I do know she was influenced by the Australian writer Louis Becke (1855-1913), who was well steeped in the magic of the Pacific.

JK: Two stories in this collection, “Through the Back Door” and “Lost Wings”, struck me as positively Bradburyesque, both in their premises and the wistful quality of the writing. Do you think this lyricism was engendered by her surroundings?

MA: “Through the Back Door” is one of my real favourites of her work. I think all her stories were inspired by her surroundings but I suspect that story had other factors that influenced it. Without giving too much away it deals with choices and whether we might want to relive our lives and maybe make any changes. I suspect most people think that at one time or another and I can’t help but wonder what was going through Grimshaw’s mind, or perhaps recent experiences, which prompted her to explore that idea. I hadn’t thought about those stories being Bradburyesque, but I think you’re right. They show how fiction can elevate our thoughts and, if needed, serve as therapy. Both these stories are, to my mind, therapeutic.

JK: Another aspect of her writing that really appeals to me is the vividness of her descriptions of island habitats. I’m thinking particularly of “The Singing Ghost” and “The Devil’s Smithy”, as well as “The Flaming Sword” and the aforementioned “Lost Wings”.

MA: Grimshaw travelled throughout the South Sea islands and became aware of life and culture in all these localities and you can tell that one of the reasons she wrote was to bring these locales alive. She doesn’t just present a setting and a story—the story is intrinsic to the surroundings and beliefs.

JK: The respect she has for the indigenous islanders is there for the islands themselves and that comes through in “The Cave”, which does not look kindly on prospectors syphoning off their resources. It’s one of the more genuinely chilling pieces in this collection.

JK: The respect she has for the indigenous islanders is there for the islands themselves and that comes through in “The Cave”, which does not look kindly on prospectors syphoning off their resources. It’s one of the more genuinely chilling pieces in this collection.

MA: “The Cave” was the first story I read by Grimshaw, which I thought highly original. At the time I couldn’t find anything else by her and it wasn’t until I developed my magazine collection, especially the British Pearson’s and the American Blue Book, that I encountered more of her work and was fascinated by the originality of the stories and how they brought the locations and cultures alive.

JK: Speaking of your search for the stories that make up Strange South Seas, how much of Grimshaw’s work did you have to read through to unearth the contents of this collection? Writers of her generation would have written across multiple genres and magazines and didn’t seem to distinguish between them.

MA: I think the total tally of Grimshaw’s stories is around 250. I’m missing perhaps thirty of those, but I read—or skim-read if I realised it wasn’t good enough or not enough fantasy—most of the other two hundred or so. I have her short story collections and read most of those twenty to thirty years ago but I still re-read those I remembered fondly. The fun part is checking out those I had in magazines but had never got round to reading and discovering something special from time to time. I didn’t do this all at once it’s been spread over years, but I went back and re-read maybe forty to whittle it down.

JK: That’s still quite an amount of reading. Perhaps the most uncanny of the stories in Strange South Seas is “The Forest of Lost Men”. Grimshaw really was capable of writing properly scary stories.

MA: I think “The Forest of Lost Men” is the closest she came to demonstrating the strangeness of the islanders’ abilities. And that otherness becomes tangible.

JK: The final story, “A Friend in Ghostland”, is a wonderful choice to round out Strange South Seas. Gentle, beautifully written, and understatedly lyrical in its delivery. Did Grimshaw ever try her hand at poetry?

MA: I’ve not encountered much by way of verse though you’re right, she could have been a good poet. Her very first appearance in print was with a poem, “To the Princess of Wales” in the Girl’s Own Paper in 1885 and I know of one other, so there may be more tucked away in minor magazines.

JK: Finally, do we know much about Grimshaw’s later life, after she moved to Papua? Did she continue to write?

MA: There is no real “later life”. She stayed in Papua as long as she could and then settled back in Australia in 1936 living initially with her brothers. She died there in 1953. She still wrote in those final years. Blue Book published stories right up to her death at age eighty-three. She had been increasingly ill, though. After all, her life in Papua, where she built herself a home, was hard work. She was a remarkable woman.

Though he worked in local government until 1998, Mike Ashley has still managed to spend over fifty-five years collecting, reading and researching popular fiction, especially fantasy, supernatural, crime and science fiction. He has compiled or edited over 100 books including reference works for children, a biography of Algernon Blackwood and a five-volume series on the history of the science-fiction magazines, though he is probably best known for the many Mammoth Book anthologies he has compiled. His Age of the Storytellers explores the British popular-fiction magazines from the 1880s to 1940s. He received the Pilgrim Award for Lifetime Achievement in science-fiction scholarship in 2002 and the Edgar Award for The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Modern Crime Fiction in 2003.