Conducted by John Kenny, June 2024

Conducted by John Kenny, June 2024

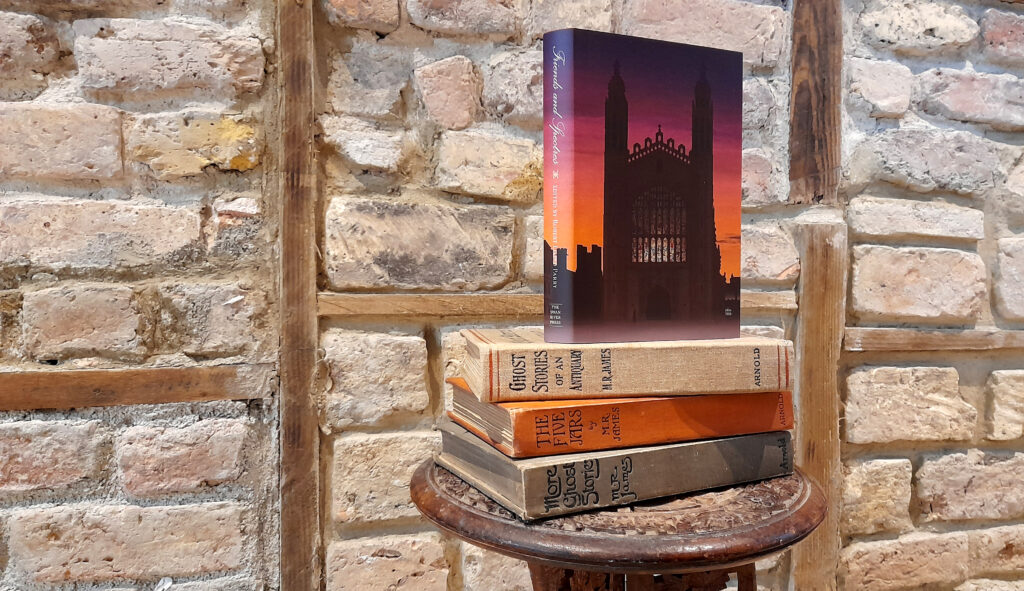

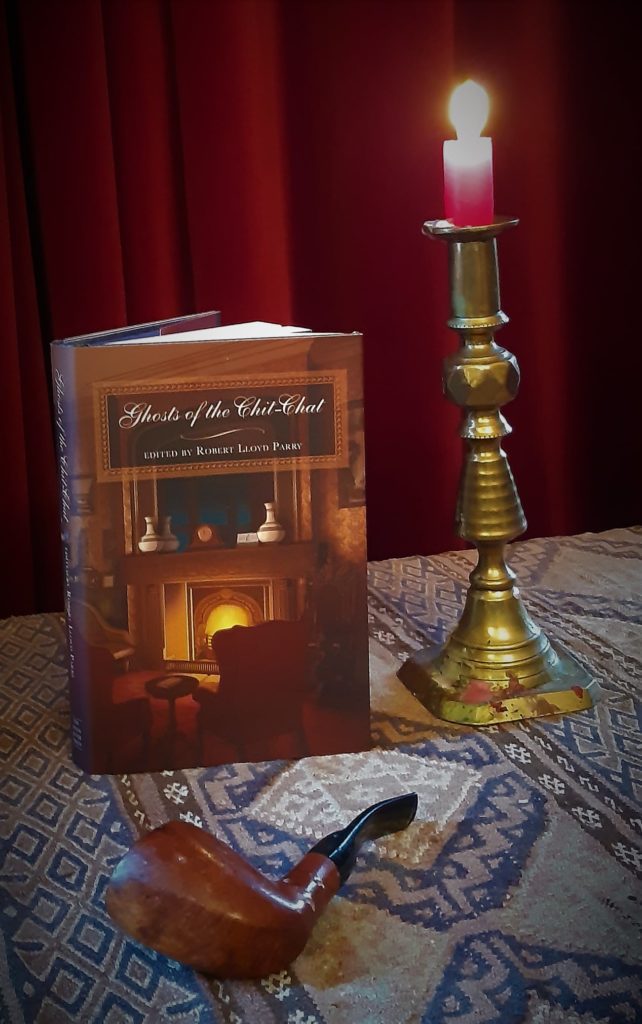

Robert Lloyd Parry is a performance storyteller and writer. In 2005 he began what he now refers to as “The M. R. James Project”, with a solo performance of Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book and The Mezzotint in MRJ’s old office in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. The Project has since encompassed seven one-man theatre shows, several films and audiobooks, three documentaries, a guided walk, and numerous magazine articles. For Swan River Press he has previously edited Ghosts of the Chit-Chat (2020) and Curfew and other Eerie Tales by Lucy M. Boston (2011). His audiobooks are available from Nunkie Audio. More information on Robert Lloyd Parry can be found at Nunkie Productions.

John Kenny: It’s clear from your introductory essays for each author featured in both Ghosts of the Chit-Chat and Friends and Spectres that M. R. James was a significant influence in at least their output of supernatural tales. Why do you think that was the case?

Robert Lloyd Parry: Well, he does seem to have been a singularly charismatic figure, someone that certain people in Cambridge, between the 1880s and 1910s, sought to emulate. He was highly respected as an academic, and loved as a college Dean and Provost. But more importantly, perhaps, he was gregarious and funny. He sought out the company of many people, and he sought—successfully—to entertain them. It’s inevitable, I think, that some of those—particularly those younger than him—would have tried to imitate him in various ways. By his own admission, E. F. Benson did. Several years MRJ’s junior, when he first went up to King’s College himself, he remembered that “intellectually, or perhaps aesthetically, I, like many others, made an unconditional surrender to his [MRJ’s] tastes . . . ”

And this gregariousness is central to the creation of the ghost stories. Almost all of them were written for social occasions—meetings of clubs like The Chit Chat or The Twice a Fortnight, or Christmas gatherings at King’s, where they were just a small part of days long house parties. Many of the writers in the two books had front row seats at MRJ’s readings; others were avowed fans of his books—and I think that the sheer quality and entertainment value of the stories inspired them to try their hands at the genre. Not all of them succeeded as well as E. F. Benson perhaps, but I’ve found it fascinating to try and trace MRJ’s fingerprints in the works that appear in the books.

JK: Tracing those influences must have involved a lot of dedicated research, and many of the stories included in Friends and Spectres can be claimed as rediscoveries of “lost” tales. What trails did you follow to ferret them out? Did you have access to Cambridge University records?

JK: Tracing those influences must have involved a lot of dedicated research, and many of the stories included in Friends and Spectres can be claimed as rediscoveries of “lost” tales. What trails did you follow to ferret them out? Did you have access to Cambridge University records?

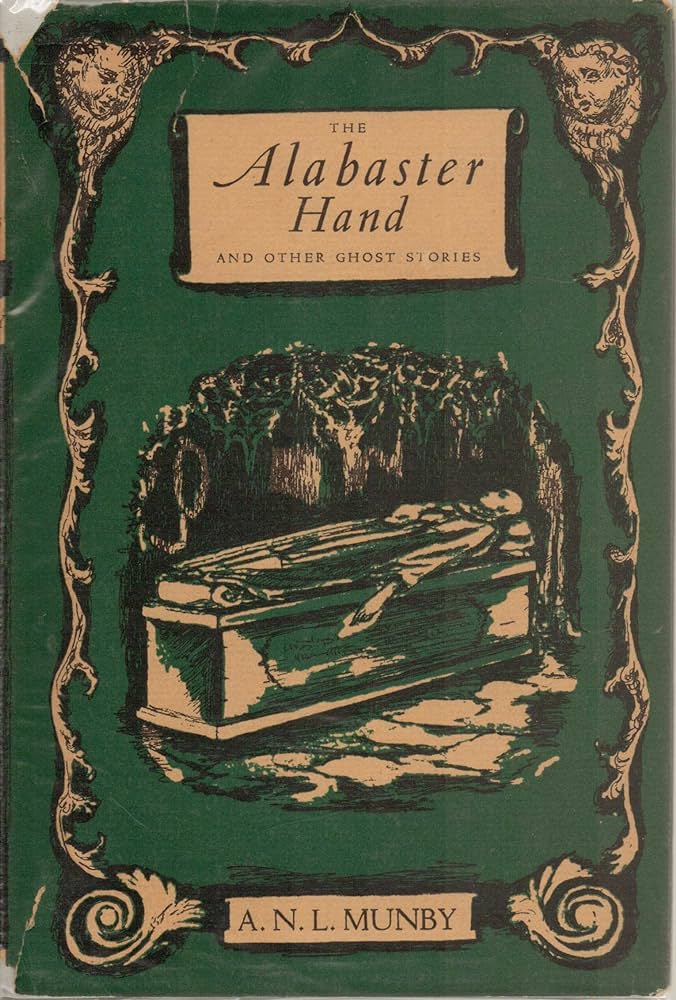

RLP: Much of the research for both collections was done in the Rare Books Reading Room of Cambridge University Library. Pleasingly, this is called The Munby Room after A. N. L. Munby, a librarian who in 1949 published The Alabaster Hand, a book of ghost stories firmly in the M. R. James tradition. There’s a framed photo of Munby on the reading room wall and I’ve spent many hours under his gaze trawling through old copies of university and college magazines. I shouldn’t say “trawling”, though, because that makes it sound like a chore, and it’s something I enjoy very much. Browsing these old magazines gives you a vivid insight into life in Cambridge in MRJ’s day—a subject in which I’ve become deeply interested.

It was from an annotation in the Munby Room’s bound copy of J. K. Stephen’s magazine The Reflector that I learned that the author of a story attributed to “Henry Doone” was in fact Arthur Reed Ropes—a fellow don of MRJ at King’s College. With that alias cracked I was able to then track down other stories by Ropes in back issues of The Cambridge Review.

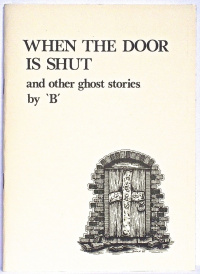

Now, news of a previously unrecognised ghost story by Arthur Reed Ropes is hardly likely to quicken anyone’s pulse (though “Seraphita” is an interesting and amusing tale). But there are a couple of other discoveries in Friends and Spectres which should be of more interest to fans of antiquarian horror. A series of ghost stories that appeared in Magdalene College Magazine in the run up to WW1, under the name of “B.”, was long thought to be the work of MRJ’s great friend A. C. Benson, and I found definitive proof of this in an unpublished part of Benson’s diary, in the Magdalene College archive—where we learn that not only did Benson write the “B.” stories, but that he read at least one of them aloud to MRJ after dinner. I also discovered a late, previously overlooked “B.” tale in the magazine—“The Sparsholt Stone”, one of his best—which is reprinted in the book for the first time since 1919.

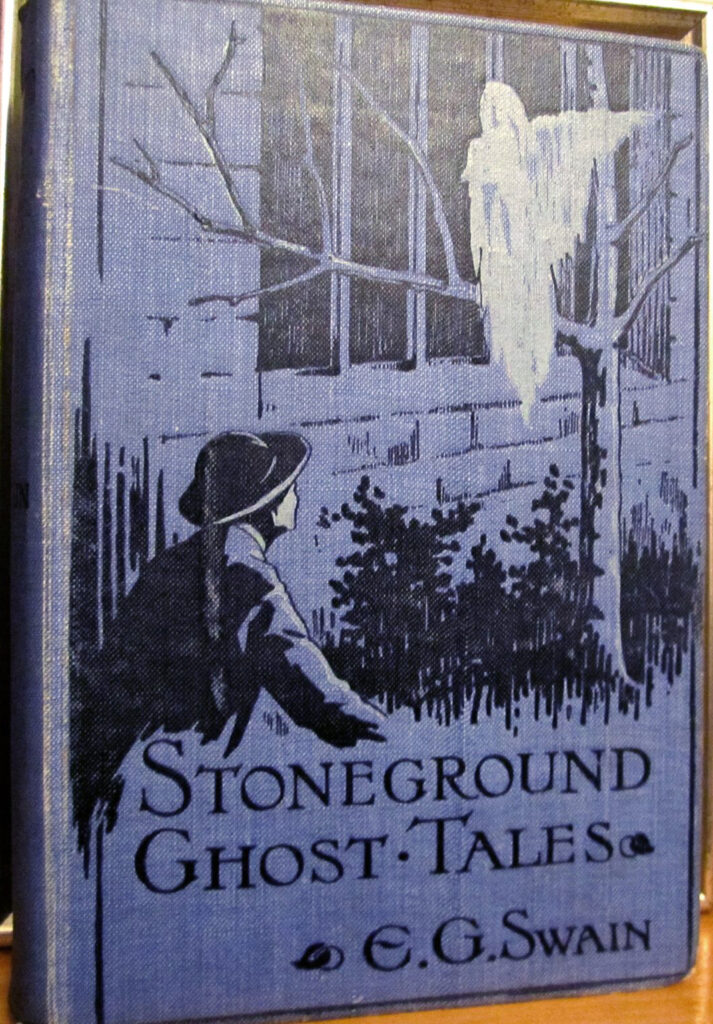

The most exciting discovery was of a lost story by E. G. Swain, author of the much loved “Stoneground Ghost Tales” and another great friend of MRJ. This came about really by simply asking the right question to the right person. The Stoneground tales were written when Swain was the vicar of Stanground near Peterborough, and as the title suggests, they were inspired by his parish. In 1916 Swain left Stanground for a church in Middlesex where he worked for eleven years, and I wondered if he’d found any inspiration there to continue with his ghost story writing career. I emailed the church to ask whether they had any records relating to Swain, and eventually the church archivist got back to me, saying that there was very little—but, out of interest, why did I ask? I told him about the book, and he emailed back an attachment that he thought I “might find interesting”. I did. What was in that attachment you can read exclusively in Friends and Spectres.

The most exciting discovery was of a lost story by E. G. Swain, author of the much loved “Stoneground Ghost Tales” and another great friend of MRJ. This came about really by simply asking the right question to the right person. The Stoneground tales were written when Swain was the vicar of Stanground near Peterborough, and as the title suggests, they were inspired by his parish. In 1916 Swain left Stanground for a church in Middlesex where he worked for eleven years, and I wondered if he’d found any inspiration there to continue with his ghost story writing career. I emailed the church to ask whether they had any records relating to Swain, and eventually the church archivist got back to me, saying that there was very little—but, out of interest, why did I ask? I told him about the book, and he emailed back an attachment that he thought I “might find interesting”. I did. What was in that attachment you can read exclusively in Friends and Spectres.

So, yes, there’s been a lot of library work and a certain amount of digging in archives, but I must also acknowledge Google. I’ve always loved going on google treasure hunts—following up clues and intuitions. These might not have ended up directly influencing the contents of the book, but they’ve greatly enhanced my knowledge, and my enjoyment of the process.

JK: Browsing through all those old magazines sounds like my idea of heaven, particularly in the environs of Cambridge University. The discovery of Arthur Reed Hope’s “Seraphita” is a very nice find. But finding definitive proof of B’s identity must have been a real thrill. And of the three stories by “B.” included in Friends and Spectres, “The Sparsholt Stone” is especially good. You refer to it as a slice of early folk horror. How far back do you think that tradition goes?

RLP: Yes, perhaps I shouldn’t have said that, because I must admit to being a bit hazy on the history of folk horror—or indeed its precise definition. Does MRJ’s “The Ash Tree”, written in the late 1890s, count as folk horror? I wouldn’t want to push that too far. Machen’s “Novel of the Black Seal” (1895) perhaps? With “The Sparsholt Stone”, it struck me that, with its violent ancient paganism surviving in the placid English countryside, it fits in with classic works like Eleanor Scott’s “Randalls Round”, yet it precedes it by ten years. I particularly like Dr. Frend’s reflections at the end of the story about there being “some secret influence” in the landscape: “I think the earth is full of these currents,” he says, “and that you and I stumbled that day upon one of them.” Perhaps that brings the tale close to what, in your recent interview with him, Mark Valentine called “borderland” or “otherworld” stories, rather than folk horror.

Anyway, I have a personal fondness for the story because it takes place in an area that I know very well. I lived for fifteen years within a very few miles of the villages it mentions—Childerly, Hardwick, Bourn, and I have walked the Portway. Disappointingly for the Bensonian tourist, perhaps, the hamlet of Sparsholt Green is his own invention.

Benson was a complicated man—not always necessarily very likeable—but the more I read by, and about, him, the more appreciative I am of his talent and character. It’s reasonably well known that throughout his life he suffered episodes of crippling depression, for which he was sometimes hospitalised, and that this informed a lot of his writing. But the “B.” stories, and “The Sparsholt Stone” in particular, I think, show something approaching a lighter side. Mr. Strutt’s rhyming couplet about the stone is (surely intentionally?) very funny. When Benson died in 1925, a book of appreciation was published with essays by people who’d known him well. MRJ had been at prep school with him and they’d remained close friends all their lives, and in his essay he sought to emphasise what a cheerful and funny person Benson had actually been.

Benson was a complicated man—not always necessarily very likeable—but the more I read by, and about, him, the more appreciative I am of his talent and character. It’s reasonably well known that throughout his life he suffered episodes of crippling depression, for which he was sometimes hospitalised, and that this informed a lot of his writing. But the “B.” stories, and “The Sparsholt Stone” in particular, I think, show something approaching a lighter side. Mr. Strutt’s rhyming couplet about the stone is (surely intentionally?) very funny. When Benson died in 1925, a book of appreciation was published with essays by people who’d known him well. MRJ had been at prep school with him and they’d remained close friends all their lives, and in his essay he sought to emphasise what a cheerful and funny person Benson had actually been.

JK: Speaking of the lighter side, F. Anstey’s “The Wraith of Barnjum” is a real hoot. And your inclusion of “The Breaking-Point” alongside it, which is a very tense and claustrophobic tale, shows Anstey’s great range as a writer. How difficult do you think it is to make humour work in tales of the macabre and uncanny? For Anstey the humour seems to be largely in his turn of phrase.

RLP: That’s an excellent description. I let forth several authentic hoots when I first read “The Wraith of Barnjum”. And I think I might have squeaked a couple of times when I read Anstey’s account of its being written. Certainly as a young man, Anstey could be extremely funny. Not all his jokes land successfully today, but some of his short stories are worth seeking out—I recommend “The Black Poodle”, “The Gull”, and “The Light of Spencer Privett’s Eyes”. Anstey’s turn of phrase is certainly a great strength; but also his sense of the absurd, and an ability to plunge his protagonists into the most awkward and embarrassing situations—all these are there in “The Wraith of Barnjum”, which he wrote when he was still an undergraduate.

And, yes, the two stories in Friends and Spectres do suggest a great range—“The Breaking-Point” is one of the best supernatural (or is it?) stories I know of that deals explicitly with the First World War. Sadly, for him and us, it wasn’t a range that Anstey made much use of—with a couple of interesting exceptions, he stuck with a comic formula that had made him famous early on, with decreasingly successful results. Not necessarily his fault—the reading public wanted what they knew.

As for humour in scary tales—I think it’s very welcome when you find it but I can’t think of too many stories that successfully integrate both humour and fear. Saki pulls it off very well. H. G. Wells’s perhaps in “The Inexperienced Ghost”. And E. F. Benson’s makes a very effective sharp turn from humour to horror in “How Fear Departed the Long Gallery”. I do think that there’s much more intentional humour in MRJ’s collected works than people tend to acknowledge. He mixes jokes and scares very well and often uses jokes to ratchet up the tension. “The Mezzotint” is a good example of that. Or “Number 13”.

As for humour in scary tales—I think it’s very welcome when you find it but I can’t think of too many stories that successfully integrate both humour and fear. Saki pulls it off very well. H. G. Wells’s perhaps in “The Inexperienced Ghost”. And E. F. Benson’s makes a very effective sharp turn from humour to horror in “How Fear Departed the Long Gallery”. I do think that there’s much more intentional humour in MRJ’s collected works than people tend to acknowledge. He mixes jokes and scares very well and often uses jokes to ratchet up the tension. “The Mezzotint” is a good example of that. Or “Number 13”.

JK: R. H. Malden’s “The Sundial” is a worthy inclusion in the book, and features a properly scary chase scene in which the hunter becomes the hunted. You note in your introduction to the story that Malden was indebted to M. R. James for introducing him to the work of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. I wonder did MRJ promote Le Fanu’s work generally among his circle of writing friends?

RLP: I’m sure he did. He seems to have promoted Le Fanu throughout his life. He read a paper on him to the Chit Chat Society in 1893, and was still lecturing on him forty years later. I suspect Le Fanu was one of those authors whose work he’d enjoy reading out loud to friends. I might be imagining things, but I sense traces of Le Fanu’s influence is several of the stories in Ghosts of the Chit-Chat and Friends and Spectres. Not in “The Sundial”, though, which on the face of it has a much more obvious model. The relationship between it and MRJ’s “The Rose Garden” is perhaps, however, not as straightforward as has been previously supposed . . .

JK: My favourite story in Friends and Spectres has to be “The Greenford Ghost” by E. G. Swain, which really ramps up the tension throughout and has perhaps the most dramatic ending of the stories included in the book. I was surprised to see from your introduction to the story that this is its first publication in book form. Did Swain publish much in book form after The Stoneground Ghosts Stories in 1912?

RLP: Yes “The Greenford Ghost” is a significant discovery for those E. G. Swain fans, and it was very exciting to come across it. I think of it as my Dennistoun moment. Until now it was thought that the Stoneground tales were all Swain had written in the ghostly vein. The only other book he was known to have published was a history of Peterborough Cathedral in 1932. But “The Greenford Ghost”, aka “Coston House”, was written and published in his local newspaper in December 1920 when Swain was vicar of Greenford—then a tiny village in Middlesex which has now been entirely engulfed by greater London.

It is as you say notably tense and dramatic—and horrible: quite unlike anything in his earlier stories. In their obituary of Swain, the newspaper that ran “The Greenford Ghost”—the Middlesex County Times—says that he wrote more than one story for them. I’ve not found anything else yet but there might be other discoveries to be made.

It is as you say notably tense and dramatic—and horrible: quite unlike anything in his earlier stories. In their obituary of Swain, the newspaper that ran “The Greenford Ghost”—the Middlesex County Times—says that he wrote more than one story for them. I’ve not found anything else yet but there might be other discoveries to be made.

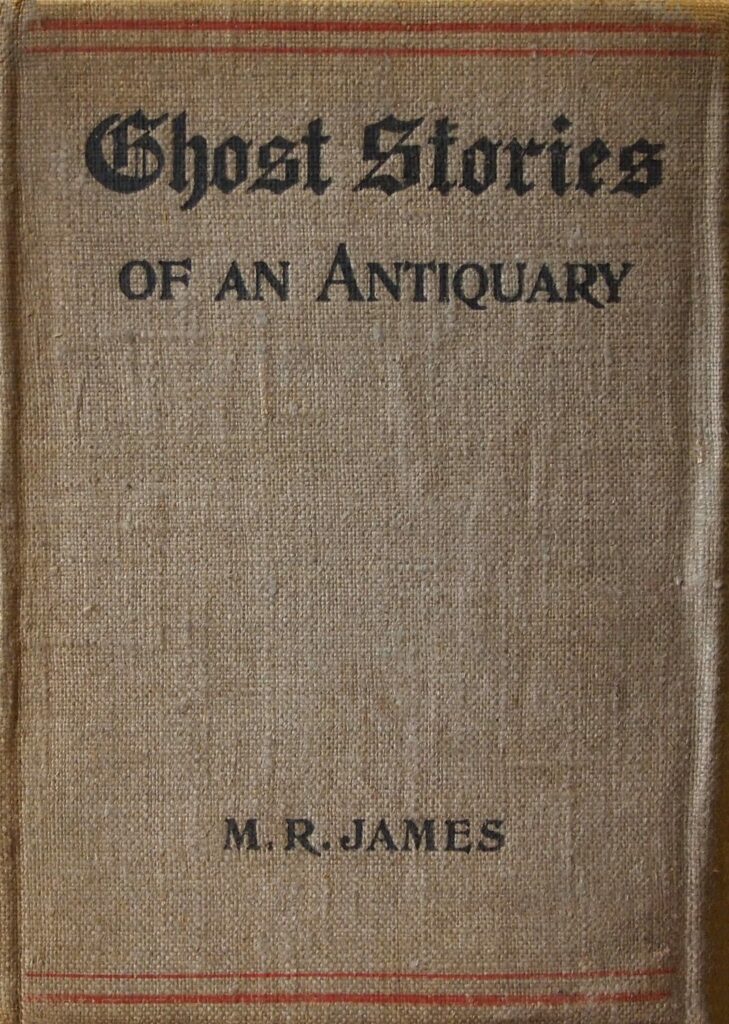

Another discovery, of less interest to ghost story enthusiasts, is that Swain pseudonymously published a volume of plays for schoolchildren in 1903—nine years before The Stoneground Ghost Tales. This was when he was Chaplain of King’s College, Cambridge and very close to MRJ. This book also contains illustrations by James MacBryde who was to illustrate Ghost Stories of an Antiquary the following year.

JK: The last time we spoke, several years ago, you were staging M. R. James storytelling performances around the UK through your company Nunkie Productions. It looks like you’ve really expanded quite a bit since then, into audio books and guided tours. Could you tell us a little more about that?

RLP: Yes, I probably had no idea when I spoke to you back then that I’d still be performing M. R. James stories all these years later. But what can I say? I enjoy it! There are now seven pairs of MRJ stories that I regularly tour in the winter, and I’ve released most of these on DVD. From when I first started performing his work, I’ve pursued an interest in the life and times of MRJ himself and this has led to making three documentaries about individual stories, and, as you mention, a literary walking walk of Cambridge—“Ghost Writers on the Cam”. This has been suspended for the last few years as I don’t live in Cambridge any more, but much of the history and stories it covered can be found in Ghosts of the Chit-Chat and Friends and Spectres.

Buy a copy of Friends and Spectres.