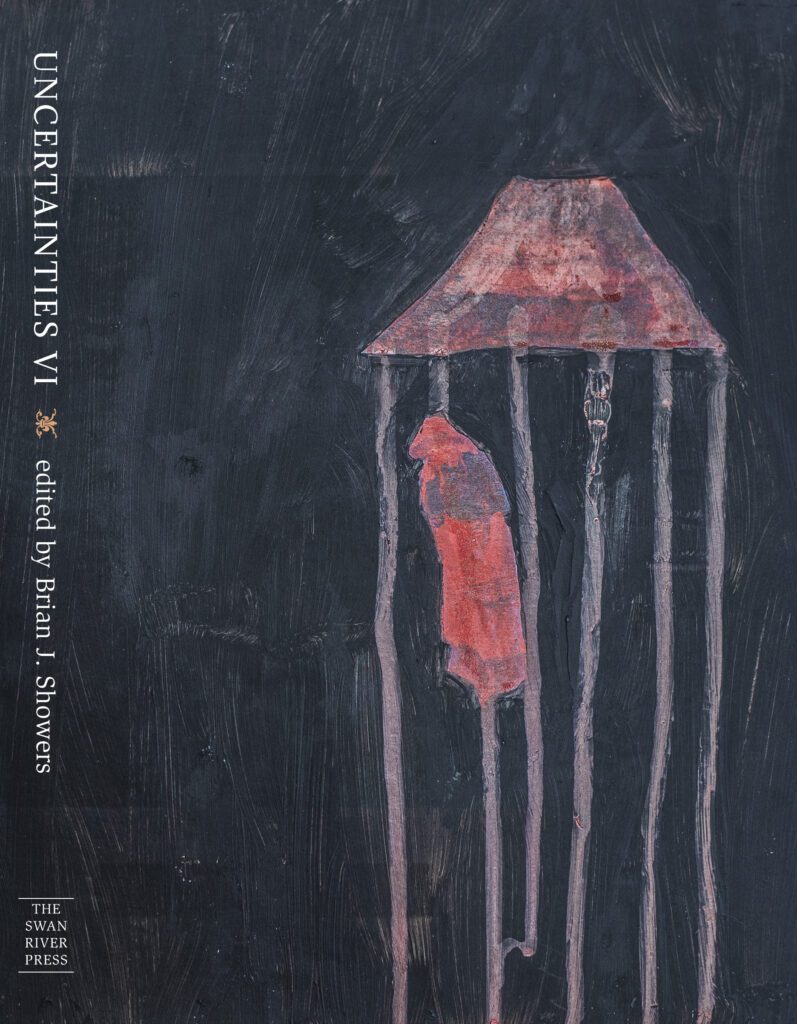

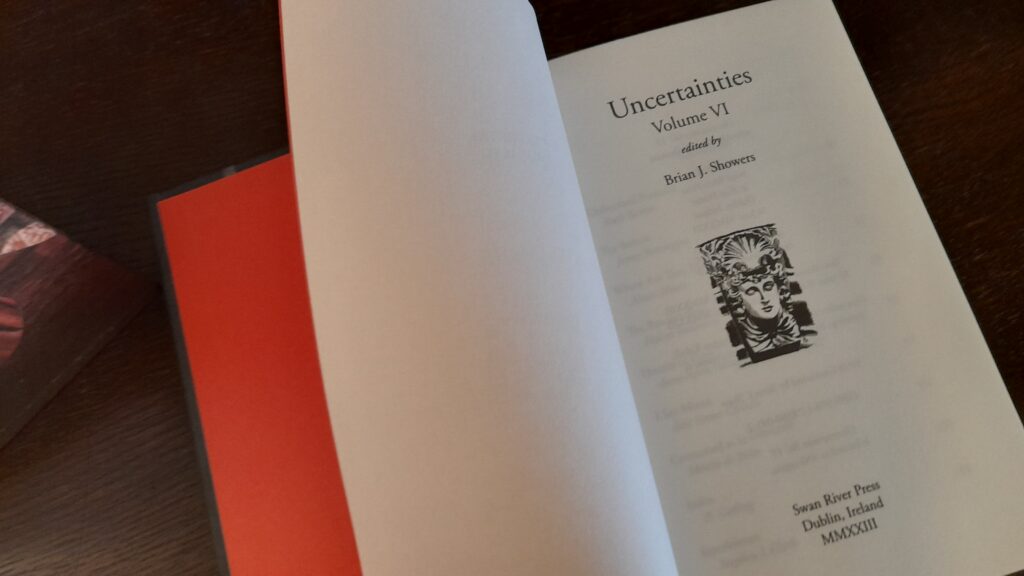

Conducted by Brian J. Showers

Conducted by Brian J. Showers

For most of our books we conduct short interviews just prior to the title’s release. In the case of an anthology, the interview is with the editor. However, for Uncertainties 6, I wanted to do something slightly different. Hoping for just a bit more insight into the genre we love, I posed a single question:

What draws you to write tales in the weird/uncanny mode?

Here are the responses . . .

Ruth Barber (“Unfinished Business”)

My stories are a form of therapy, a vehicle for processing negative emotions such as grief, sadness, disappointment, and unfairness. The black humour comes from the random and surreal circumstances in which misery is often meted out.

I had an unhappy childhood where the expression of emotion was discouraged. I began writing from a young age: my stories and poems became an acceptable outlet for my feelings. As fiction my feelings could be safely expressed in a way that avoided any need for responsibility, accountability, or indeed resolution.

I work as a criminal lawyer and write in my spare time. Growing up in an atmosphere of unfair condemnation I feel a degree of empathy with people facing criminal charges and my ability to emotionally disassociate allows me to deal with many unpleasant and traumatic cases. I am, of course, professionally bound to keep the details of my cases confidential however I collect discrete shards of experiences and weave them together to create fantasy tales.

My tales are therefore formed from feelings and moments—the creak of a second hand sofa in a café, the shine on a cheap suit, the smell of fear in the courtroom. My tales examine the secret ticks and vices we adopt to make life bearable and the delusions we create to avoid confronting our demons.

I am the person who knows before you call, the person who can extrapolate your mood from the frequency of your WhatsApp logins, and who predicts the future from the lyrics in the next song on the radio. I know the real reason you just spoke to that person and when you are lying. But I will never tell.

Most importantly dear reader know that I write for myself and not for you. Through my tales you gain the privilege of a glimpse inside my head. Be wary as to whether it is truly a place you want to visit.

James Everington (“The Switch”)

The honest answer to this is probably “because I can’t write anything else”. I’ve a relatively broad taste when it comes to reading, but my attempts to write realistic slices of life, comedic fantasy, or—god help me—poetry have always fallen flat. And I think of it as a plus, for a writer, to eventually realise the narrow circumference of your talent and concentrate your efforts there. And it’s not as if I’m missing out: writing about the strange, the ghostly, the nebulous is my realism, reflecting life as I feel it. The hidden yet nagging sense of something unexplainable or jarring or out of sync with reality. And it’s my poetry, too: a chance to play with language and form and style in the pursuit of capturing in words something fleeting yet indelible. All of which is a highfalutin way of saying that, for me, reading and writing uncanny tales scratches an itch that other genres can’t.

Alison Moore (“Where Are They Now?”)

Alison Moore (“Where Are They Now?”)

Some years ago, I wrote a horror novelette under a pseudonym for the Eden Book Society series published by Dead Ink Books. Writing a horror story was a natural and satisfying way for me to process the almost unreal experience of donating a kidney. Analysing that process—the relationship between the experience and the story—for a subsequent article clarified my understanding of how and why the uncanny, in which the familiar and the strange coexist, was uniquely suited to this narrative about transplantation and its very literal breaching of boundaries. The kidney donor in my novelette has a persistent sense that none of this is real, and the surreal quality of the experience is reflected in imagery encompassing stories and dreams and horror films. She feels herself gradually disappearing, from her name to her receding gums. “I swear to God,” says a visitor, “there’ll be nothing left of you soon.” There’s a sense of inevitability: when she’s given some paperwork to sign, giving her permission for the procedure to go ahead, she finds she’s already signed it. Her abdomen is marked with a thick black arrow pointing towards the kidney they’re going to take. “If this mark comes off,” the doctor says, “it will be drawn on again.” I took these and other details in the story directly from the diary I was keeping, but what was innocent in reality gains a sinister quality within the fictional narrative, so that the everyday seems to be giving way to something stranger. The procedure went according to plan and the real-life story was a good-news item on local TV, but the horror story, the version that acknowledges and channels the weirdness of it all, captures what it felt like and as a result feels more true.

Naben Ruthnum (“The Bracken Box”)

I’ve been trying to write weird fiction since I started writing. I certainly think there are other kinds of fiction worth reading and writing, but I can’t deny that the weird ones are special for me, that the great and good ones create an artistic effect that is beyond craft or technique, coming close to what I think is most worthwhile in art. That’s why I so rarely put one out there; I think that this piece in Uncertainties is my only successful piece of weird short fiction.

Aickman talked about the shared qualities between poetry and the strange story, which is true in so many ways. I find writing weird fiction to be as difficult as I find writing poetry, and I continue to keep attempting both. I’m starting to succeed, fitfully, with the weird tale, but with every new attempt to flesh an idea or an impression, there come moments when I feel as unarmed and amateur as I did when I first started writing anything. This is a mode that exposes; while strange stories can be suggestive, can lead without going, if there’s nothing to them, we all can tell that there are no ghosts to be found.

Anne-Sylvie Salzman (“Houses of Flesh”)

I was seven when I tried to read my first “adult” book, The Secret of Sarek (L’Île aux trente cercueils), by Maurice Leblanc; I say “try”, because I stopped after a few pages of sombre omens and mutilated corpses (I tackled it a few years later and loved it, of course). But it left its mark—and more than that. The decayed bodies went on rotting in the recesses of my brain and gave birth to most splendid flowers—as would the painter Odilon Redon. At some point, this conflated with a keen love of nature inherited from my parents (naturalists/entomologists/

Eric Stener Carlson (“I See Minza”)

That’s a bit of a strange question. I mean, I get it. “Uncanny” is supposed to mean something just slightly off, something that doesn’t feel real.

But that presupposes that there’s one stream of “reality” (composed of common sense, and fair rules of the game, and generally-accepted behaviour), and then there’s another—almost inexistent—stream of “unreality” (where people act inexplicably, where rules don’t apply, where behaviour is cruel, barbaric and fantastic).

Here’s one example of our attempt to push the uncanny into a quiet, little corner. Recently, I watched a TV show from the UK on ancient belief systems (like druids and the early Christian church). The commentator, trying to explain the social context of the Black Death, said something like, “You see, back then, people believed in something called the ‘devil’, and they thought it surrounded them all the time.”

Really? You don’t believe the devil surrounds us on all sides, trying to tempt us to destruction? I do. I believe in an ever-loving, benevolent God, so I also believe in the polar opposite. I’m not saying the devil is a flesh-and-blood creature (in fact, we may be our own devils), but that doesn’t make him any less real. I’ve investigated war crimes in Argentina and the former Yugoslavia, so I know that for a fact.

Although we’d like to think otherwise, “strange” things are woven into the very fabric of our lives. Once, on an abandoned railway platform in Poland at about 3 a.m., a 300-lb former wrestler appeared out of the darkness, and challenged me to punch him in the stomach as hard as I could (I declined). And in college, there was a “glitch” in my answering machine that made it call up a friend and leave my “Please leave your message at the beep” message. She thought maybe it was a plea for help (it wasn’t, at least not from me).

Why do I write weird tales? It’s my attempt to outline our dappled existence, where what we call the “extraordinary” and the “ordinary”, “natural” and “supernatural”, “real” and “uncanny”, all swirl together on a typical Monday morning. What’s “weird” about that is how often we fail to recognize it.

Méabh de Brún (“Consumed as in Obsessed”)

Méabh de Brún (“Consumed as in Obsessed”)

I love ghosts. I love ghosts and goblins and things that go bump in the night. I love gothic hauntings in old creaking manors and the folkloric horror of things within the woods. Sometimes people ask me, but do you really believe? Inconsequential. Irrelevant. I am having a ball. But there’s a subtle difference between spooky and strange, and it’s the strange that truly unnerves and fascinates. Those weird uncanny stories that are not so easily explained by a restless, roaming spirit or an old folk-tale. Senseless events without rules, reason or motive that leave you lonely in the half-dark asking, but why? but why? These kinds of stories may not cause a burst of terror in the moment, but they worm beneath the skin. They unsettle. They unnerve. It’s always the inexplicable that leaves you lying awake at night, turning it over your mind like a tongue probing a rotting tooth. I press the weird against the mundane to highlight the horror of the everyday, and to write about the things that are truly scary. The banal and boring evil of a housing crisis. The creeping dread of losing a beloved friend. I would stride up the steps of the haunted manor with a skip in my step and a song in my heart. No ghoul could compare with living through late stage capitalism. Simone Weil once said, “Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.” By writing in the uncanny, I can add a splash of colour to the grey. A jewel-tone spread of strange and sourceless mould across clean concrete. When I need to get to grips with real fear, it’s the uncanny that gives me the weird gloves to do so. Yes, things are still bad, but now they’re interesting. And after all, in the face of inexplicable horror one should always continue to aim for that glorious goal of having a ball.

Stephen J. Clark (“Interference”)

Writing for me involves being receptive to my imagination and unconscious mind. Once an idea, memory or image emerges then the process of creative play begins, and I interpret and delve into the images and ideas to see where they will take me.

To an extent the story has a life of its own. If I set out with a personal experience or memory or dream in mind, I often discover something unexpected: some long-forgotten detail or surprising insight. It’s this potential for revelation that inspires me. I find that revelation is inextricably linked to my experience of language, which involves encountering arresting metaphors or lucid phrases as part of the process and pleasure of writing.

I think of language as a fabric partly composed of unconscious threads, of personal memories yet also ancient images and ideas, so my writing is a way of engaging with those hidden seams between intimacy and myth. For me, writing from the imagination involves attempting to describe what often resists expression, to utter what would otherwise remain lost, concealed or forbidden, to reach into those zones of uncertainty and possibility. For the fabric can become a map, charting journeys into the domains of the grotesque and the Marvellous. Exploring this personal mythology of poetic images and resonances is a method of catharsis too: of attempting to lay ghosts to rest or to name demons.

For me, writing is a kind of waking dream, using my imagination to form a dialogue between the conscious and the unconscious. Whether discovered by chance or through deliberate exploration, I’m fascinated by the experience of encountering alluring and disturbing images and ideas, and my art and stories are the residual evidence of those encounters.

A. K. Benedict (“The Sands”)

Explaining why I write the uncanny would require more words, time, and money for therapy than I currently have, but it is something to do with seeing strangeness in a world that most people think of as “normal”. It’s about being slantwise. Catching the sniff of ghosts in dust motes, fixing restless spirits in ink, bones in words. The uncanny makes more sense than most because we know less than nothing, about anything, and there is joy in acknowledging the twisting of shadows

David Tibet (“Dreams As Red Barn”)

When I was young in Malaysia

I loved the Hebrew Bible

And the New Testament

And the Biblical Apocryphal Writings

Especially Coptic texts

And Apocryphas led me to M. R. James

And his The Apocryphal New Testament

And then I fell in LOVE with his GHOST STORIES

I also loved Enid Blyton

And her NODDY books

And She Wrote in one of them

Amen Amen Amen:

It isn’t very good

In The Dark Dark Wood

In the middle of the night

When there isn’t any light . . .

It isn’t very good

In The Dark Dark Wood . . .

And ever since READING those HALLUCINATORY WORDS . . .

I have searched for The Dark Dark Wood

And found her many times

Amen Amen Amen

David Tibet, Hastings, 4 VII 2023

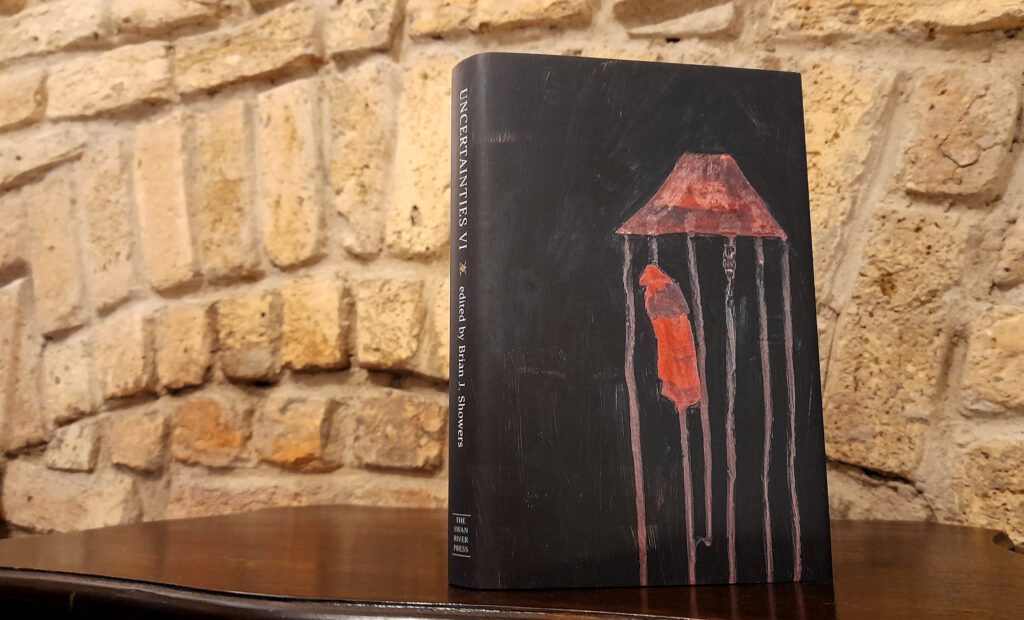

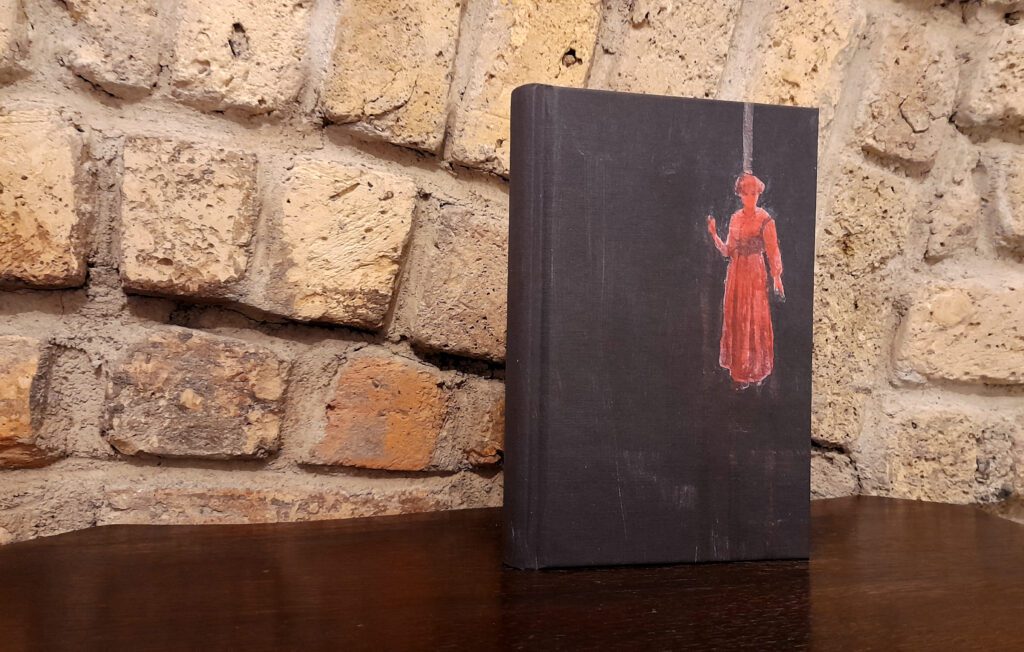

Buy a copy of Uncertainties 6.