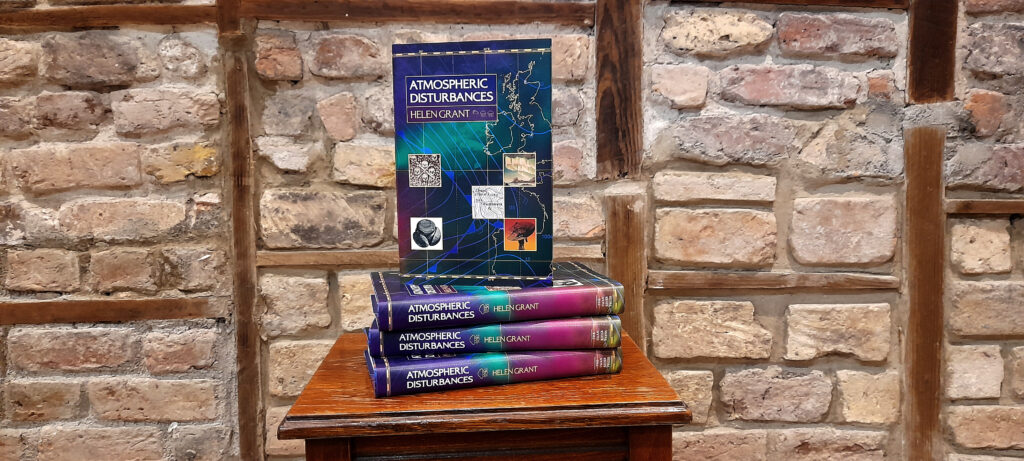

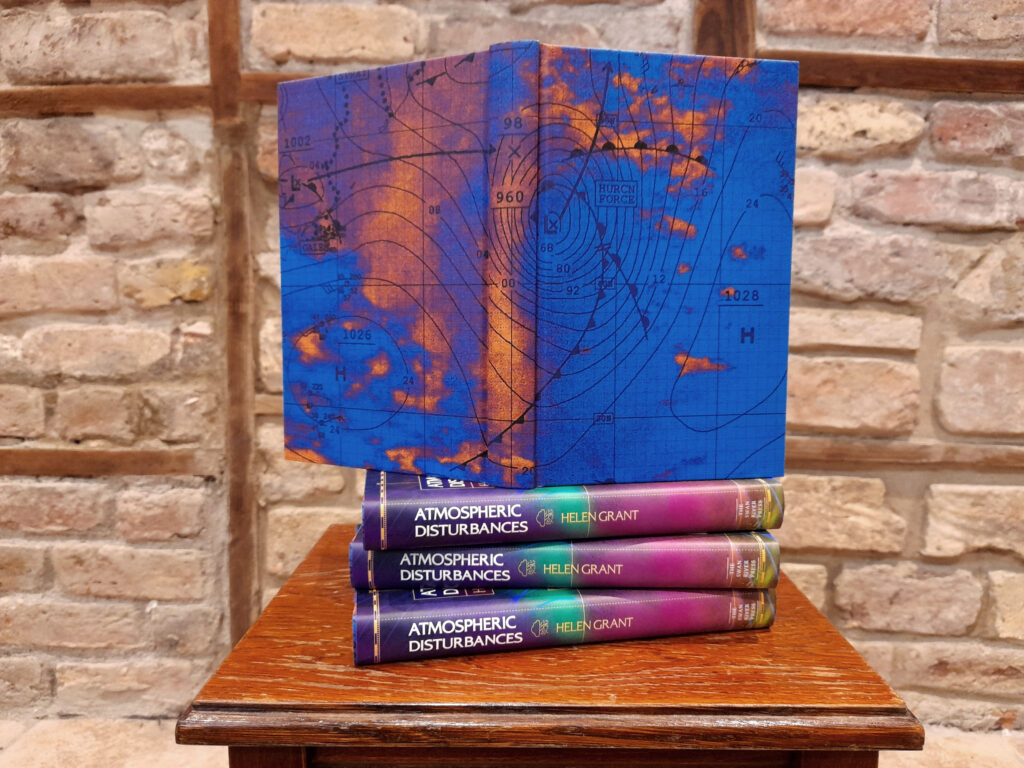

Atmospheric Disturbances

Helen Grant

Availability: In Print – Hardback

“In its dim depths living things scurried and fluttered, but human voices were very rarely heard.” – The West Window

A glimpse of a grotesque illustration combined with the onset of fever instigate a descent into a hellish nightmare. In the wine cellar of an abandoned mansion, something alluring yet ominous is sealed inside a vintage bottle. At the end of a claustrophobically narrow alley lies a gilded façade opulent enough to tempt a thief. And forty miles out to sea, a naturalist on a lonely island hears voices through the radio telling stories of unimaginable disaster—and hope. In her second collection, award-winning author Helen Grant visits Flanders, Paris, and the remotest parts of Scotland, examining themes of transgression, repercussion, and revenge.

- Read John Coulthart’s blog post on Atmospheric Disturbances

Hardback edition limited to 425 copies.

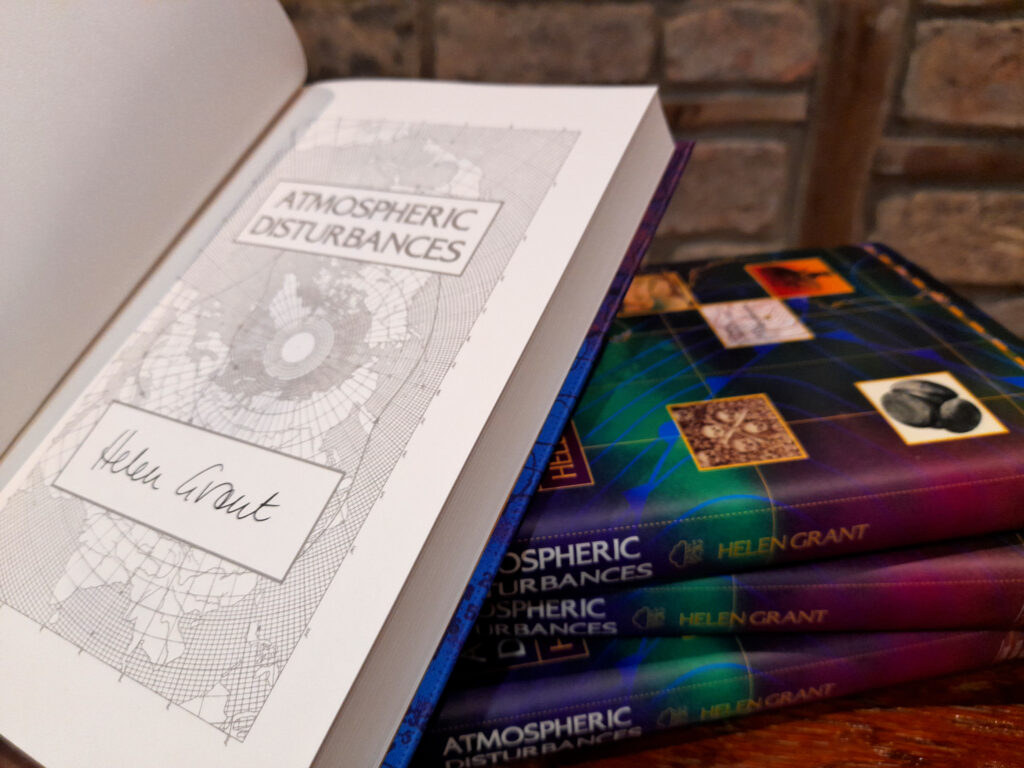

Signed by the author.

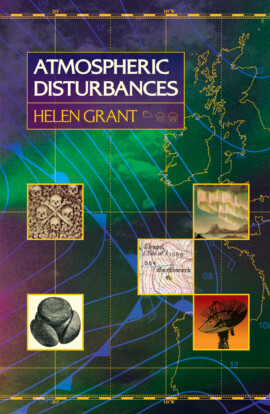

Cover art by John Coulthart

ISBN: 978-1-78380-049-0 (hbk)

Contents

“Mrs. Velderkaust’s Lease”

“The ’50”

“Gold”

“All Things That Are Reproved”

“The Field Has Eyes, the Wood Has Ears”

“The West Window”

“Friday”

“The Lost Maze”

“Chesham”

“The Valley of Achor”

“The Wynd”

“The Edge of the World”

“Atmospheric Disturbances”

“Sources”

“Acknowledgements”

“About the Author”

Helen Grant

Helen Grant has a passion for the Gothic and for ghost stories. Joyce Carol Oates has described her as “a brilliant chronicler of the uncanny as only those who dwell in places of dripping, graylit beauty can be”. She lives in Perthshire with her family, and when not writing, she likes to explore abandoned country houses and swim in freezing lochs. Her novels include the Dracula Society’s Children of the Night Award-winning Too Near The Dead (2021) and Jump Cut (2023) about a notorious lost movie.

Read more“An excellent writer of the uncanny.” – Ellen Datlow, Best Horror of the Year

“For those who like gothic and ghostly fiction this volume is a true feast.” – Hellnotes

“Grant is an experienced thriller writer who grasps suspense and the subtly macabre.” – Everlasting Club

“This is an excellent collection, surely one of the best of 2024, if not the best . . . Helen Grant combines old school supernatural mystery with modern psychological horror.” – Supernatural Tales

“One of the strongest single author collections of uncanny and supernatural tales I’ve read in a long time.” – You’re Reading

Atmospheric Disturbances by Helen Grant; cover art by John Coulthart; jacket production by Meggan Kehrli; edited by Brian J. Showers and Timothy J. Jarvis; copyedited by Jim Rockhill; typeset by Steve J. Shaw.

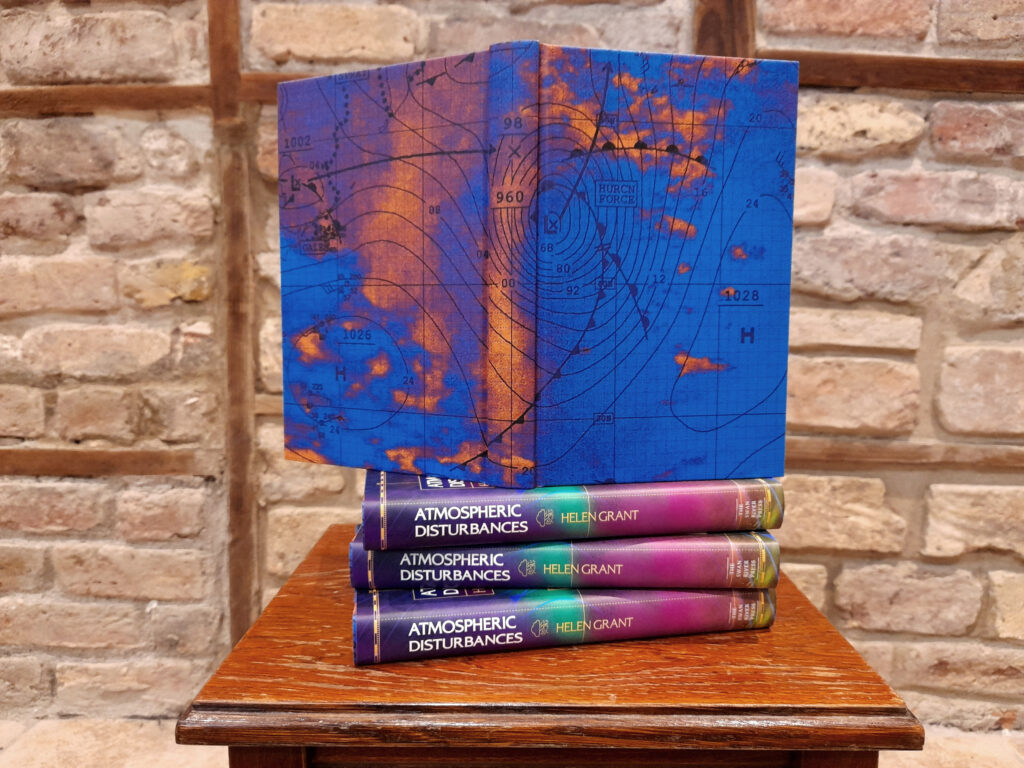

First Hardback Edition: Published on 11 November 2024; limited to 425 copies, the first 100 of which are embossed and hand-numbered; dust jacketed; illustrated cloth-printed boards; endpapers (Wibalin Old Gold 507); iv + 235 pages; lithographically printed on 90 gsm cream paper; sewn binding; head- and tail-bands (Winterband 537 bright blue); printed by TJ Books; ISBN: 978-1-78380-048-3.

“Excavating at the Edges of the World”

“Excavating at the Edges of the World”

Conducted by John Kenny, September 2024

Helen Grant is the author of short story collection The Sea Change & Other Stories (Swan River Press 2013) and her novels include Ghost (Fledgling Press 2018), Too Near the Dead (Fledgling Press 2021), which was winner of the Dracula Society’s Children of the Night Award, and Jump Cut (Fledgling Press 2023), which is about a notorious lost movie called The Simulacrum. Joyce Carol Oates has described her as “a brilliant chronicler of the uncanny as only those who dwell in places of dripping, graylit beauty can be”. Helen lives in Perthshire, Scotland, and is a fan of ghost story writer M. R. James, exploring abandoned country houses, and swimming in freezing lochs.

John Kenny: What is it about Gothic stories that appeals to you?

Helen Grant: Oddly enough, when I started writing professionally I didn’t realise I was squarely in the Gothic genre. I’d been naturally drawn to Gothic novels and stories from childhood. The Hound of the Baskervilles was a big fave of mine when I was ten, and I went on to read The Mysteries of Udolpho, The Monk, The Castle of Otranto, Dracula, etc. and later novels like Rebecca without giving much thought to the genre. In more recent years I took an online course in the Gothic from the University of Stirling and it clicked . . . I guess there are a variety of things I love about the Gothic. I like the fact that it is often spine tingling and creepy but not too brutally gory—terror rather than horror, I have heard people say. I like stories with isolated protagonists (I’m not a party animal myself and I like stories where the heroine has to survive on her wits and try to work out what is going on). I love folklore, and old buildings too—one of my hobbies is exploring abandoned country mansions here in Scotland. But the big thing I love about the Gothic is that it is filled with emotion. When something terrifying happens, I’m interested in how that makes people feel. How do they respond to it? How do they cope? Can they tell what is real? I find that fascinating.

JK: I note that you’re a fan of M. R. James’s short stories and have spoken at a couple of conferences devoted to his life and work. I’m curious to know what aspects of his work you discussed.

JK: I note that you’re a fan of M. R. James’s short stories and have spoken at a couple of conferences devoted to his life and work. I’m curious to know what aspects of his work you discussed.

HG: Yes, I have been a fan of M. R. James’s ghost stories for as long as I can remember. When I was a child, my father used to retell them to us on long car journeys! I still re-read them regularly.

In 2015 I was a plenary speaker at M. R. James and the Modern Ghost Story, a conference held in the Leeds Library. On that occasion I spoke about the demonology of “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book”, a topic I have also written about for the Ghosts & Scholars Newsletter. I’m fascinated by that story, and particularly by the fact that nothing in it appears to be random—including the dates on which various eldritch things occur.

In 2018 I spoke at another conference, Through a Glass Darkly, this time in York. On that occasion I related the true story of Father Nikola Reinartz, a German priest who travelled to England to view Steinfeld’s missing stained glass windows, after their whereabouts were revealed in “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”. Father Reinartz corresponded with M. R. James, who was instrumental in helping him to view the glass. In order to piece this story together I translated some articles from the German, published in the early 1900s in an appallingly spiky Gothic script that was very difficult to read!

More recently, in March 2024, I spoke to the Dracula Society in London about M. R. James’s foreign story locations. I’ve visited most of those: Steinfeld, St. Bertrand de Comminges, Viborg, Marcilly-le-Hayer. During the same talk I also discussed the use of technology in the stories, because that’s something that increasingly interests me. At the 2015 conference in Leeds I heard Aaron Worth, an Associate Professor at Boston University, speaking about the “Haunted Cinematography of M. R. James” and that made a big impression on me because I didn’t naturally associate M. R. James with technology. I tended to think: old books, quill pens, odd bits of church architecture. But there’s actually quite a lot of technology in his stories, and it’s frequently malign (think of the magic lantern in “Casting the Runes” for example). My most recent novel, Jump Cut, has old technology at its heart, and it has some very Jamesian moments in it.

JK: Speaking of cinematography, your latest novel, Jump Cut, deals with a “lost” film called The Simulacrum. Is this an actual film? I read something about it online that seems to suggest it is.

JK: Speaking of cinematography, your latest novel, Jump Cut, deals with a “lost” film called The Simulacrum. Is this an actual film? I read something about it online that seems to suggest it is.

HG: So far as I know, there is no actual film called The Simulacrum. There are several simply called Simulacrum (some of them indie shorts, I think) but not The Simulacrum. When I was deciding on the name of the movie in the book, I tried really hard to find one that wasn’t already a film, and especially not one everyone would immediately recognise. I did have various names in mind, but I liked that one because the word comes from the Latin word for a likeness or image, and I felt that gave it a properly ominous tone!

JK: You mentioned earlier your love of exploring abandoned country mansions and I note “The West Window” in your new collection, Atmospheric Disturbances, revolves around this very pursuit. Are there many such abandoned mansions in Scotland and can you just walk in?

HG: There are, amazingly, quite a few abandoned mansions in Scotland, and I have often thought that perhaps this is because many country houses were in quite remote locations; if they were in the south of England, for example, they would have been pulled down, boarded up or turned into a hotel long ago. Often, you can just walk in (though not always). Sometimes they have been fenced off, and sometimes it just isn’t possible to go inside because there is so much debris: fallen timbers, lengths of guttering and masonry. The mansion in “The West Window” is loosely based on Dunmore Park House near Falkirk, although I took a few liberties with the topography, turning the house 360° and blanking out one window. I have visited it four or five times. The room in the story, the library, really was a library and is now much as I have described it. In spite of its ruinous state it does still have a kind of beauty.

JK: The sense of place you create in your stories is vivid. particularly in stories like “The Valley of Achor”, “The Edge of the World”, and “Atmospheric Disturbances”. I see the setting for “The Valley of Achor” is Perthshire, where you live. Is there a burial mound or ruined chapel where you’ve mentioned it?

JK: The sense of place you create in your stories is vivid. particularly in stories like “The Valley of Achor”, “The Edge of the World”, and “Atmospheric Disturbances”. I see the setting for “The Valley of Achor” is Perthshire, where you live. Is there a burial mound or ruined chapel where you’ve mentioned it?

HG: Ah, interesting you should ask about that particular story location! Well, the place itself is Glen Almond, which is not far from Aberfeldy, and like my heroine Ann, I have cycled down it (and jolly cold it was, too). There is indeed a burial mound or cairn, at a site called Clach Na Tiompan which also incorporated a stone circle, mostly destroyed now. South-west of it there is another site, called Tomenbowie, which has a burial ground very much like the one in the story. I went to see that out of pure nosiness—I love poking about in old kirkyards and ruins. There may or may not have been a chapel associated with this burial ground. The Canmore database, which has records for both of these sites, says “Chapel (Period Unassigned) (Possible)”. Having walked all around the burial ground, I could not see any sign at all of a chapel. If there ever was one, it is no longer visible or not extant at all. That was what gave me the idea for the story, really. Was there a chapel, and if so, why isn’t there one now?

JK: That’s fascinating. Several of your stories in Atmospheric Disturbances have at their centre a kernel of authenticity. I’m thinking specifically of “The Edge of the World” and its petrospheres. The alternate theory as to their purpose that the main character advances is genuinely intriguing.

HG: I’m a bit obsessed with petrospheres! I find it extraordinary that there are these things which clearly took a lot of time and skill to make, and we don’t know what they were for. I feel it ought to be obvious, but it isn’t. They must have some function beyond being merely decorative because in a society that was so much closer to subsistence level than ours is, you wouldn’t sit and laboriously carve something out of stone for no reason. People have suggested that they were fishing weights or (that most irritatingly vague explanation) that they had some “ritual significance”, but we just don’t know. I don’t think they are a uniform weight either so they probably weren’t used for weighing things. Blackhouses sometimes have nets over their thatched roofs and those have stones on them to weight the ends down, but the stones are much bigger than the petrospheres so that seems unlikely. My son is an archaeologist but I can’t really get him to speculate about this either! I was going to go nuts thinking about it, so in the end I made up my own explanation.

JK: Another story in the collection that uses a real object as its inspiration is “The Field Has Eyes, the Wood Has Ears”. There are a number of facets to the story that combine to generate a genuine sense of terror: the outbreak of Covid-19, the worsening migraine, the bizarre sketch by Hieronymus Bosch.

JK: Another story in the collection that uses a real object as its inspiration is “The Field Has Eyes, the Wood Has Ears”. There are a number of facets to the story that combine to generate a genuine sense of terror: the outbreak of Covid-19, the worsening migraine, the bizarre sketch by Hieronymus Bosch.

HG: Yes—it’s my one Covid-19 story. I haven’t been tempted to set an entire book during the pandemic. It’s hard to explain why. When we were in the thick of it, I was very concerned about how or whether to incorporate it into the novels I was writing (I opted to set Jump Cut just before it, because it didn’t seem credible that the carers of a very rich 104-year-old woman would let strangers visit during Covid) and I’m not sure there was an ideal answer to that.

The short story was prompted by several different factors. I have long been somewhat fascinated by the effects of ergot poisoning (hmmm, reading that remark back, it sounds very dodgy) and I think I have read that some people suspect Hieronymus Bosch’s wild and nightmarish paintings were prompted by it. It’s also true that some migraine meds do contain ergotamine. I can imagine that during the brain fogging many people experienced when they had Covid, a person might lose track of how much of something they had taken, and when. So the set-up is not unrealistic. As for the Bosch sketch, well, that just gives me the meemies. I went to the Bosch exhibition in s-Hertogenbosch some years back and saw a lot of his work. The big oil paintings are surreal and horrifying, but there is something about that simple little sketch that is chilling. The unease followed me home.

JK: One of my favourite stories in Atmospheric Disturbances is “Mrs. Vanderkaust’s Lease”, perhaps because the denouement is implied rather than spelled out. And “Chesham” is similar (although completely different), in that the ending is freighted with all sorts of implications. I sometimes think this approach can really ramp up the tension of a story.

HG: It’s interesting that you picked those stories out. I don’t say I never do pulp and gore (one of my recent stories for Nightmare Abbey was about carnivorous goldfish) but on the whole I think I tend towards the “less is more” approach. Letting the reader’s imagination do the work can be more effective than spelling it all out. At the end of “Mrs. Velderkaust’s Lease”, would the story be improved by describing what has happened in graphic detail? I don’t think so. I mean, Ellen Velderkaust herself doesn’t want to think about what has happened. Plus I think there is a risk of spilling over into the ridiculous. It’s taste, though, isn’t it? I guess some folks love to roll in gore . . .

HG: It’s interesting that you picked those stories out. I don’t say I never do pulp and gore (one of my recent stories for Nightmare Abbey was about carnivorous goldfish) but on the whole I think I tend towards the “less is more” approach. Letting the reader’s imagination do the work can be more effective than spelling it all out. At the end of “Mrs. Velderkaust’s Lease”, would the story be improved by describing what has happened in graphic detail? I don’t think so. I mean, Ellen Velderkaust herself doesn’t want to think about what has happened. Plus I think there is a risk of spilling over into the ridiculous. It’s taste, though, isn’t it? I guess some folks love to roll in gore . . .

As for “Chesham”, I think that kind of scenario is literally the stuff of nightmares—the feeling that there is something urgent you should have done or noticed. Incidentally, the house is based on the one I lived in until my mid-teens, and the topography of the town is accurate. Actually some of the minor events in the story are true too. Hmmm. I’m not sure I’m going to think about that too carefully.

JK: Finally, the title story “Atmospheric Disturbances”, which aptly closes the collection, manages to be both deeply disturbing and somewhat hopeful at the end. Do you think the existence of humankind might only be one chapter in the story of this planet?

HG: I was glad the collection closed with that story, because it’s one of the rare ones with an optimistic ending. Humankind is absolutely one chapter in the story of this planet, given that we have been here a relatively short time compared to the dinosaurs. Whether we’re the last chapter is another thing. “Atmospheric Disturbances” springs from a deep-rooted fear shared by those of us who grew up during the Cold War. Occasionally, decades later, I still have nightmares about nuclear attacks. The “four-minute warning” was a horrible concept—long enough to panic, not long enough to reach your loved ones.

In the story, there is a lot of ambiguity. We only know as much as Rob, the protagonist, knows. Given where he is, he may never know anything more. But yes, there are elements of hope at the end. Perhaps that sums up how I feel about the topic—terrified about what could happen, hopeful that it won’t.

If you’d like, you can read John Kenny’s full review of Atmospheric Disturbances.