As many of you already know, 2014 is an important year for Gothic literature. This coming August marks the 200th birth anniversary of Dublin’s “Invisible Prince”, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. While today hardly recognised in his native country of Ireland, his influence has spread around the globe, not only for his sensational Gothic page-turners, but also for his indelible contributions to the genres of the classic ghost story and modern crime novel. Would there even be Dracula without “Carmilla”?

In addition to Le Fanu’s bicentenary, this year also marks the 150th anniversary of Uncle Silas. Perhaps Le Fanu’s best known novel, Uncle Silas was serialised (under its original title “Maud Ruthyn”) in the Dublin University Magazine from July-December 1864. The three-decker novel was then promptly issued in late December by Richard Bentley. Now is the perfect time to revisit the sinister rooms and gloomy passages of Bartram-Haugh. I know what I’ll be re-reading this autumn . . .

- Looking to buy multiple issues? Check out our Green Book Bundle.

Paperback edition limited to 350 copies.

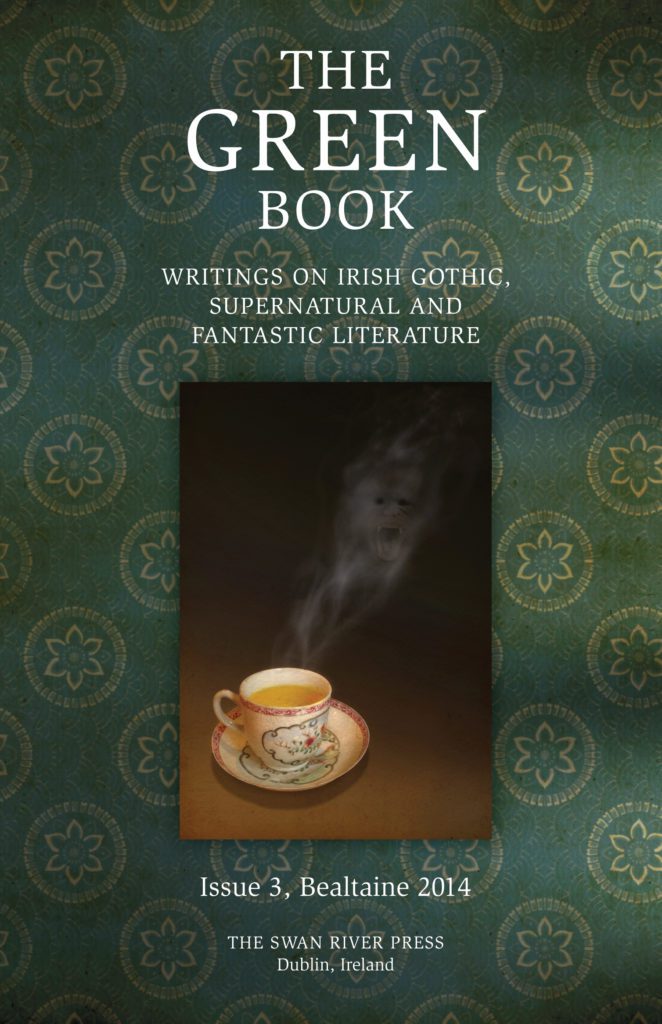

Cover art by Jason Zerrillo

Editor’s Note by Brian J. Showers

ISSN: 2009-6089 (pbk)