Conducted by John Kenny, October 2024

Conducted by John Kenny, October 2024

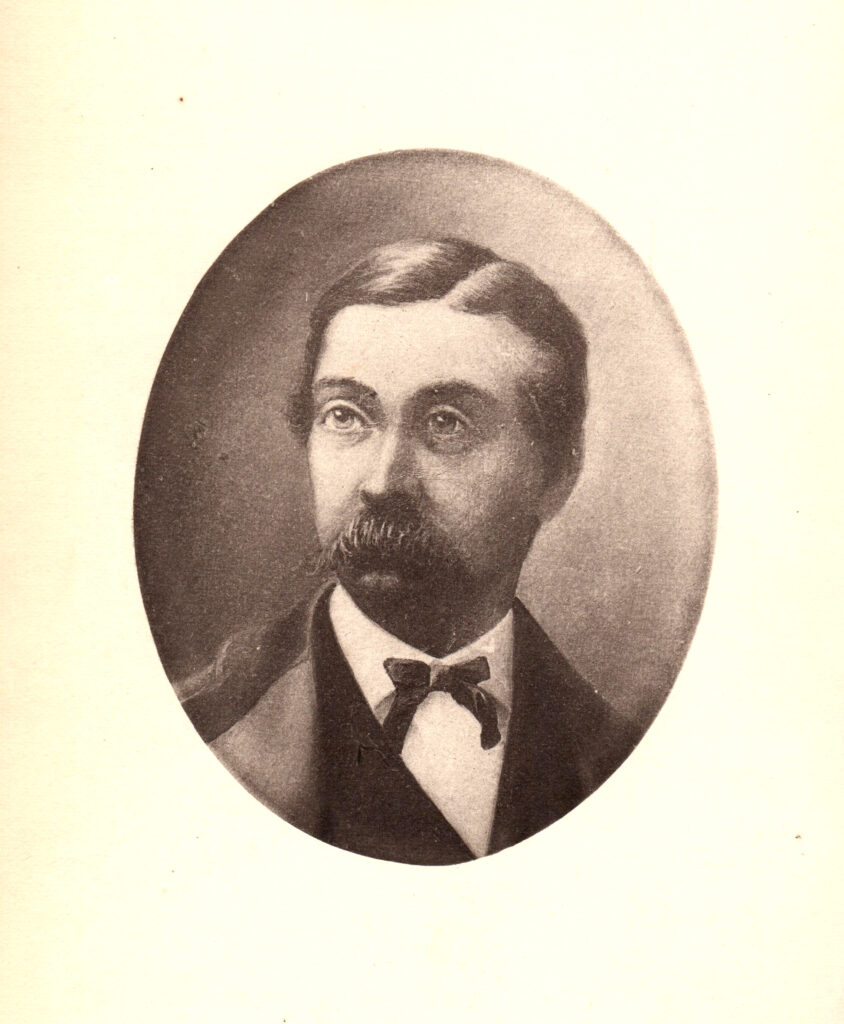

John P. Irish is an educator and independent researcher who specializes in the philosophical ideas of John Locke and John Adams. His dissertation topic was on the social thought of Fitz-James O’Brien. He has earned Master’s degrees in Philosophy and Humanities as well as a Doctorate in Humanities from Southern Methodist University. He lives in Bridgeport, Texas with his wife Elizabeth and their five children: Tom, Annie, Teddy, Lucy, and Holly—otherwise known as their pets.

John Kenny: How did you first encounter Fitz-James O’Brien’s work and what was it about his work that drew you in?

John P. Irish: In the summer of 2015, while working on an independent study course for my M.A. under the guidance of my advisor and mentor, the late John Lewis from Southern Methodist University’s English Department, I created a course called “Famous Monsters in Literature”. I began by selecting the monsters I wanted to focus on and identifying the quintessential literary works for each. Some were obvious choices—Dracula for the vampire, Frankenstein for the reanimated dead, Jewel of Seven Stars for the mummy, and The Werewolf of Paris by Guy Endore for the werewolf. But I struggled to find the perfect ghost story. I eventually decided on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, the only work on my list that I hadn’t read before.

However, after reading it, I felt somewhat disappointed. It didn’t feel like a traditional ghost story to me. I expressed this to Professor Lewis, who agreed it might not fully satisfy that expectation. He suggested I explore other options and handed me an anthology of ghost stories from his collection. As I browsed the table of contents, I came across a name that stood out—Fitz-James O’Brien—and his story “What Was It? A Mystery”. I was instantly captivated by it. Professor Lewis and I had a fascinating discussion afterward, dissecting the nuances of the story. Though he wasn’t particularly familiar with O’Brien, we both found the story rich and thought-provoking.

That fall, I began my Doctorate at SMU and, due to the demands of full-time teaching and graduate work, I didn’t have much time for leisurely reading or research on O’Brien. So, I shelved the idea for another time.

Fast forward to 2017: I met with my department head to discuss potential dissertation topics. At the time, I was set on writing about Edgar Allan Poe, having spent years shaping my coursework and research around him. However, during the meeting, my advisor asked, “What new scholarship can you contribute on Poe?” When I couldn’t come up with a strong answer, he urged me to find a different topic. I left the meeting feeling deflated, unsure of where to turn next. Then, it hit me—Fitz-James O’Brien! I mentioned him to Professor Lewis, who responded, “Now that would be an interesting subject!” O’Brien was relatively unknown, and there was little existing scholarship on him. I realized I had found my topic.

Fast forward to 2017: I met with my department head to discuss potential dissertation topics. At the time, I was set on writing about Edgar Allan Poe, having spent years shaping my coursework and research around him. However, during the meeting, my advisor asked, “What new scholarship can you contribute on Poe?” When I couldn’t come up with a strong answer, he urged me to find a different topic. I left the meeting feeling deflated, unsure of where to turn next. Then, it hit me—Fitz-James O’Brien! I mentioned him to Professor Lewis, who responded, “Now that would be an interesting subject!” O’Brien was relatively unknown, and there was little existing scholarship on him. I realized I had found my topic.

The first major challenge was finding his complete works. Outside of a few older collections, many of his writings were hard to locate. I managed to gather some well-known stories but needed more. So, I began scouring the internet, contacting universities and libraries, and even reaching out to the National Library of Ireland, which proved very helpful. Over time, I compiled nearly everything he wrote that had been documented.

What continues to impress me about O’Brien is his foresight. His ideas were remarkably modern for his time. I believe that he serves as a significant bridge between Romanticism—by which he was heavily influenced—and Realism, though he never lived to see that movement flourish. His urban Gothicism is also crucial to literary history. Outside of Poe and George Lippard, I believe O’Brien may be one of the most significant figures in that tradition. Furthermore, his literary style was far ahead of its time. His short fiction incorporates modernist elements such as metafiction, unreliable narration, intertextuality, stream of consciousness, autofiction, and hyperreality—long before these techniques became hallmarks of the modernist movement.

O’Brien’s stories, though varied in quality, show clear progression over his career. I often tell my students that had he lived longer, he might have become a cornerstone of American literature, alongside figures like Poe, Melville, Irving, and Hawthorne—all of whom influenced his work deeply.

JK: O’Brien left Ireland at quite a young age and fetched up in New York, via London. I wonder do you see a difference in what he wrote while in Ireland and what he came to write in New York?

JPI: Absolutely! The works we have from O’Brien in Ireland are primarily poetry. While his Irish poetry can be a bit scattered, it reveals early signs of his social, political, and economic concerns, as well as a deep love for Ireland, particularly its geography. I disagree with Francis Wolle, O’Brien’s first and only biographer, regarding O’Brien’s feelings toward his homeland. Wolle claims O’Brien was embarrassed about being from Ireland, but I don’t believe that to be the case. While it’s true that Irish immigrants faced significant prejudice and discrimination in antebellum America, O’Brien continued to write about Ireland. One of his most successful plays, A Gentleman from Ireland, was centered on an Irish immigrant to America. Additionally, one of his most sentimental poems, “The Ballad of the Shamrock”, was published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in March 1861. I find ample evidence to support the view that O’Brien was not embarrassed about his Irish roots. If he had been, it’s unlikely he would have continued to make Ireland a focal point of his published work.

When he moved to London in 1849, O’Brien began exploring fantasy, with his first two stories (really fragments) falling within the fairy-tale fantasy genre. During this period, he continued to write Romantic poetry, some of which had already been published, and these works were republished both in London and later in America. You can sense he was still figuring out what kind of writer he wanted to be. His time in London was a period of experimentation. He initially gained recognition through his submissions to a definition competition—somewhat reminiscent of Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary. O’Brien’s submissions were satirical and humorous—perhaps not as sharp as Bierce’s, but still strong enough to catch the attention of the editors. This recognition led to his first payments for writing.

Once he relocated to America, O’Brien fully embraced the speculative genre. Just before leaving London, he had a story published in Charles Dickens’s newspaper Household Words in 1851 titled “An Arabian Night-mare”, which we believe to be his first horror story. After arriving in America, he began to grow and evolve into the writer we now recognize. In his first year there, he started a series of stories and poems collectively called “Fragments from an Unpublished Magazine”. These works were connected through a mythical book edited by a character named Adam Eagle. The unnamed narrator of the fiction believes Eagle is involved in some mystical cult, possibly practising dark magic. The narrator randomly selects passages from the volumes of the unpublished magazine, presenting the reader with poems, stories, or fragments depending on what he finds. One of the highlights of this series is the first poem the narrator shares with readers, titled “Madness”. This poem bears a strong resemblance to the works of Poe, delving deeply into the unraveling of a person’s mental state with chilling precision and intensity.

Once he relocated to America, O’Brien fully embraced the speculative genre. Just before leaving London, he had a story published in Charles Dickens’s newspaper Household Words in 1851 titled “An Arabian Night-mare”, which we believe to be his first horror story. After arriving in America, he began to grow and evolve into the writer we now recognize. In his first year there, he started a series of stories and poems collectively called “Fragments from an Unpublished Magazine”. These works were connected through a mythical book edited by a character named Adam Eagle. The unnamed narrator of the fiction believes Eagle is involved in some mystical cult, possibly practising dark magic. The narrator randomly selects passages from the volumes of the unpublished magazine, presenting the reader with poems, stories, or fragments depending on what he finds. One of the highlights of this series is the first poem the narrator shares with readers, titled “Madness”. This poem bears a strong resemblance to the works of Poe, delving deeply into the unraveling of a person’s mental state with chilling precision and intensity.

O’Brien’s time in London was pivotal for his development and growth as a writer, setting the stage for his later success in America.

JK: He also embraced a Bohemian lifestyle early on, when the whole concept was in its infancy. How did he come in contact with it?

JPI: There’s an intriguing gap in O’Brien’s life between March 1847 and July 1848. O’Brien claimed that during this time he was studying law at Trinity College, but unfortunately, there’s no evidence to support this. Some have speculated that he may have served in the army, but I have a different theory. I believe O’Brien was on a Grand Tour in France. His mother hinted at this in a letter (she talked about the O’Grady tradition for such a thing), and considering O’Brien’s remarkable fluency in French language and literature, it seems likely he would have further developed these skills during a Grand Tour, as many wealthy young men of his class did at the time. I also think this is where he first encountered the Bohemian lifestyle. His writing shows clear influences from French writers and thinkers, which supports this idea.

By the time he arrived in London in 1849, O’Brien had fully immersed himself in London’s cultural scene. Knowing his personality, it’s no surprise he found his way onto Grub Street, the hub for writers and journalists. He spent lavishly on books, fine clothing, and food, blowing through his inheritance in just over two years—so he must have thoroughly enjoyed his time there. I suspect he continued to interact with Bohemian circles during this period, as that lifestyle clearly fascinated him.

However, it was in America that O’Brien truly embraced the Bohemian lifestyle. In 1855, Pfaff’s Beer Hall, opened by a German immigrant, became the hub for New York’s Bohemian writers. Many of the most influential authors of the time gathered there regularly, including Walt Whitman, with whom O’Brien socialized. O’Brien also contributed to The Saturday Press, a Bohemian newspaper edited by his friend Henry Clapp Jr. Pfaff’s became more than just a tavern—it was a vibrant meeting place for the exchange of ideas, creativity, and good beer.

O’Brien was well-acquainted with Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème, published between 1847 and 1849, and paid homage to the Bohemian movement with his 1855 short story, “The Bohemian”. This tale masterfully blends elements of horror and reflects O’Brien’s literary influences, evoking shades of Poe’s “The Gold Bug” and Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”. As with much of O’Brien’s fiction, “The Bohemian” contains autobiographical elements, revealing his deep fascination with and connection to the Bohemian lifestyle. The story stands as a testament to O’Brien’s immersion in and admiration for the movement.

O’Brien was well-acquainted with Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème, published between 1847 and 1849, and paid homage to the Bohemian movement with his 1855 short story, “The Bohemian”. This tale masterfully blends elements of horror and reflects O’Brien’s literary influences, evoking shades of Poe’s “The Gold Bug” and Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”. As with much of O’Brien’s fiction, “The Bohemian” contains autobiographical elements, revealing his deep fascination with and connection to the Bohemian lifestyle. The story stands as a testament to O’Brien’s immersion in and admiration for the movement.

JK: For all that he only wrote when absolutely necessary, to make money to get by, he produced a large body of work in his short life. And the quality of a lot of that work would indicate that he enjoyed the process.

JPI: I agree, O’Brien is a tough nut to crack. He had a habit of diving into projects with great enthusiasm, only to abandon them before completion—a pattern he repeated several times throughout his career. I can certainly sympathize, as I have a few unfinished projects of my own that I keep putting off in favor of other things. But when O’Brien was fully engaged in a project, he was incredibly prolific, writing at a rapid pace. He could write a poem in a single night and head to the publisher the next day to see who was interested.

As you noted, much of his writing was driven by the need to pay his bills—or, perhaps more accurately, to throw extravagant parties and have others foot the bill. I’m not sure we would have gotten along had we lived in the same era; he was a rough character who often got into fights. Still, he was quite popular, especially within his social circle. It saddens me to think about the potential he had, and what he could have accomplished had he lived to old age. He was a natural storyteller with great versatility in his craft. His imagination was boundless, and I believe that had he lived longer, he would have produced even more remarkable works for future generations.

One challenge in studying O’Brien is determining how much he actually wrote. Much of what he published was anonymous, which was common practice at the time, making it nearly impossible to establish a definitive canon of his work. Unfortunately, he didn’t leave us a list of his publications. He did, however, leave a list of stories he intended to collect in a personal edition—most of which have been discovered—but we’re still left with an incomplete view of his literary output.

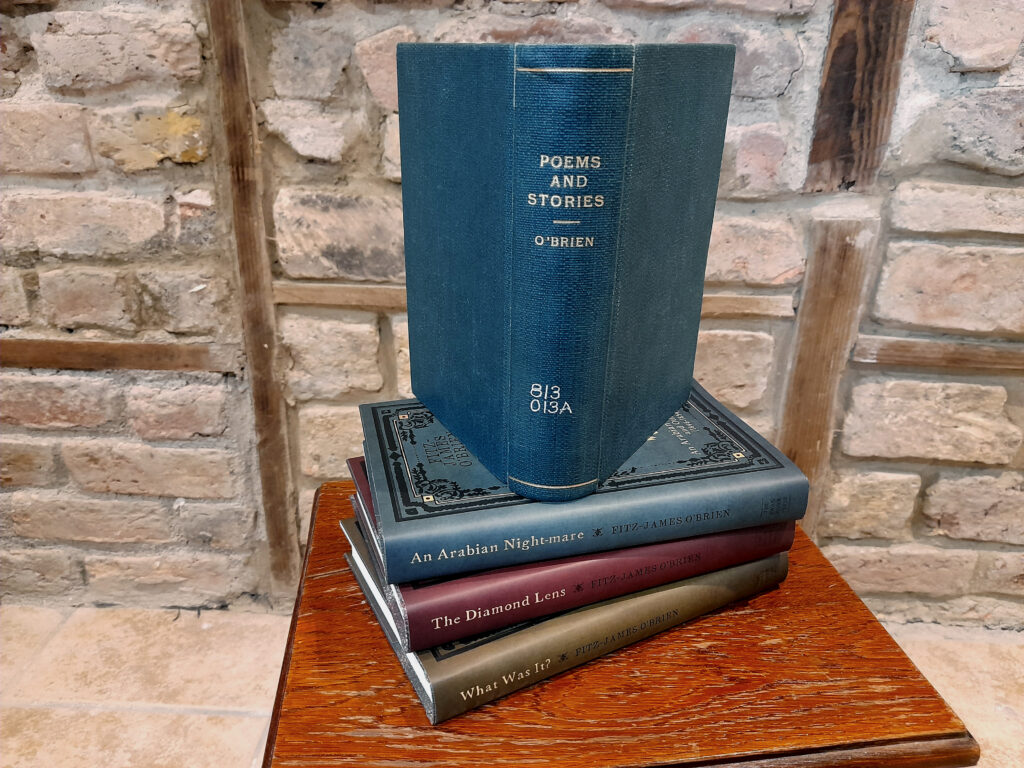

JK: You have, however, managed to pull together, in these three volumes, the most complete collection of O’Brien’s fantastic literary output to date, which includes poetry, a play, and over three dozen short stories. How much digging did you have to do to ferret out this material?

JPI: It was an enormous undertaking, and I can’t imagine how this kind of research would have been possible before the internet! The librarians at SMU were incredibly helpful, and I made extensive use of resources from other universities and public research libraries to gather this material. I compiled everything O’Brien wrote, including his non-speculative works, which comprise roughly two-thirds of his total output. So, if we only consider his speculative fiction and poetry, we miss a significant portion of his body of work. He was incredibly prolific.

Originally, this collection began as a resource for my dissertation, which, incidentally, didn’t focus on his speculative works. I examined his social, political, and economic thought in his non-speculative fiction and poetry. My dissertation, titled “ ‘Of Nobler Song Than Mine’: Social Justice in the Life, Times, and Writings of Fitz-James O’Brien”. While I aimed to position O’Brien as a precursor to today’s social justice movement, my committee felt he was more about raising awareness than advocating for direct action. Still, I uncovered a wealth of fascinating material that revealed his deep engagement with social issues. To fully understand his perspectives, I needed to read as much of his work as possible. Since most collections only include his better-known speculative stories, I took it upon myself to search for everything. It took me about two years to reach a point where I felt I had a solid collection of his writings. I even continued gathering additional material after completing my dissertation.

Originally, this collection began as a resource for my dissertation, which, incidentally, didn’t focus on his speculative works. I examined his social, political, and economic thought in his non-speculative fiction and poetry. My dissertation, titled “ ‘Of Nobler Song Than Mine’: Social Justice in the Life, Times, and Writings of Fitz-James O’Brien”. While I aimed to position O’Brien as a precursor to today’s social justice movement, my committee felt he was more about raising awareness than advocating for direct action. Still, I uncovered a wealth of fascinating material that revealed his deep engagement with social issues. To fully understand his perspectives, I needed to read as much of his work as possible. Since most collections only include his better-known speculative stories, I took it upon myself to search for everything. It took me about two years to reach a point where I felt I had a solid collection of his writings. I even continued gathering additional material after completing my dissertation.

For this new Swan River Press collection, we are presenting a substantial portion of O’Brien’s writings, everything we classify as speculative fiction, poetry, and fragments—even a melodrama play. Volume one of this set contains all new material, with the exception of “An Arabian Night-mare” and a few others. None of this material has been seen since the 1850s. I’m genuinely excited to offer readers and researchers the opportunity to explore O’Brien’s earliest fiction and poetry—it’s immensely rewarding to think of others being able to engage with his work on such a comprehensive level.

JK: Perhaps the key to O’Brien’s general philosophy can be most easily found in his poetry, which, as you say, was primarily influenced by the Romantic era poets. “Forest Thoughts” and “The Lonely Oak” are good examples. But you can see his exploration of these ideas, a love of nature and a distrust of meddling in the natural order of things, in many of the short stories.

JPI: These two poems are among my favorites, as they capture several important themes in O’Brien’s work: nature as a space for reflection, memory and the passage of time, mortality and endurance, solitude and companionship, legacy and cultural identity, and the cycle of life and death. “Forest Thoughts” takes a broader, more philosophical approach, celebrating nature as a universal sanctuary for contemplation and spiritual continuity. “The Lonely Oak”, however, offers a more personal, culturally resonant view, with the oak symbolizing Ireland’s heritage and serving as a comforting emblem of resilience. Together, these poems reveal O’Brien’s Romantic perspective on nature as a vessel for reflection, continuity, and identity across both personal and cultural dimensions.

As you mentioned, his short fiction also provides insight into his philosophical world-view. One aspect I appreciate about O’Brien is his deeply philosophical approach to all his writing. Having multiple degrees in Philosophy, I find O’Brien a rich source of intellectual material. I would characterize his philosophy as a moderate scepticism—not in the radical sense of doubting all knowledge, but as a belief that while absolute truth may be elusive, we can gain practical knowledge that helps us navigate the world. This perspective comes through in “What Was It? A Mystery”, where characters Hammond and Escott encounter an invisible being. They can confirm its presence by touch, yet visually, it’s undetectable. This story demonstrates how our senses can produce inconsistent or contradictory perceptions of reality, challenging us to question whether they can serve as reliable sources of epistemological or metaphysical truth.

We see similar explorations in O’Brien’s dream narratives, where he investigates the boundaries of liminal spaces. His characters often experience something intense, only to awaken and realize it was a dream—though the dream felt real while it lasted. If we can’t distinguish dreams from waking experiences, how can we trust that we’re truly awake? This reflects O’Brien’s familiarity with French philosophy, notably Montaigne’s skepticism and Descartes’ exploration of dreams and perception. French thinkers were pioneers of these philosophical ideas, which clearly influenced O’Brien’s work.

O’Brien also displays a kind of cosmic sense of justice. He observes that the innocent suffer, often at the hands of those with free will, and humanity is frequently the cause of much of the world’s suffering. However, a sense of cosmic justice seems to prevail, not to prevent suffering (which, as O’Brien knew well, affects children, women, and animals—topics central to my dissertation) but to balance the scales. His horror stories “The Diamond Lens” and “The Wondersmith” illustrate this idea. In “The Diamond Lens”, Linley, a scientist with noble goals, sacrifices ethics in pursuit of his ambitions, while in “The Wondersmith”, Herr Hippe, a figure of pure malice, suffers his deserved fate. Though innocent characters endure hardships, those who inflict harm often meet consequences themselves. This sense of justice also runs through his non-speculative works. For example, in one of his earliest poems, “The Famine” (1846), he critiques both the British for mismanaging the crisis and the wealthy Irish for ignoring the suffering around them, warning them that they will face judgment: “And, when life is ended here, / In another, higher sphere, / Voices thus shall greet your ear.”

Some of my favorite non-speculative poems, like those in his “Street Lyrics” series—“The Beggar Child”, “The Crossing Sweeper”, and “The Street Monkey”—powerfully convey empathy for the most vulnerable in society. These works reflect O’Brien’s ethos and pathos in raising awareness for children, women, and animals, illustrating his commitment to social justice themes.

JK: You can see his empathy for the poor and disenfranchised in his speculative work too, in stories such as “Three of a Trade” and “The King of Nodland and His Dwarf” and poems such as “The Spectral Shirt”.

JPI: One of the chapters from my dissertation was published several years ago in the Journal of New York History, where I examined O’Brien’s views on the Civil War and slavery. In that article, titled “Fitz-James O’Brien Hands in His Chips: His New York Writings on Slavery and the Civil War”, I focused on his fantasy story “The King of Nodland and His Dwarf”. It’s intriguing that, despite being attuned to the struggles of the dispossessed and downtrodden—a theme prevalent throughout his work—O’Brien remained largely silent on the subject of slavery. My article explored possible reasons for this silence. I concluded that O’Brien tended to write about what he was directly exposed to and had experienced first-hand. In 1850s New York, one might encounter freed African Americans, but the stark realities of slavery as it existed in the South were not part of his everyday experience, as he never visited the Southern states. Racism and discrimination were certainly present in the North, but the institutions of slavery were far less visible (they were there: insurance, banking, shipping, etc., New York was the hub of industries related to the institution of slavery, the mayor actually floated the idea of the state seceding with the South!). What O’Brien did witness daily, however, were the dire conditions of poverty, child labor, and the mistreatment of women and animals—issues he often addressed in his writing.

It’s also important to distinguish between an author and their characters, a distinction that can be challenging. Poe faced this as well; while he was a melancholic figure, he wasn’t the same as the characters he wrote about. O’Brien shared a similar situation. For instance, in his story “The Diamond Lens”, the character Linley is a despicable figure who makes anti-Semitic remarks about his neighbor, Simon, whom he eventually kills. One of my students once suggested that this made O’Brien himself anti-Semitic, which took me by surprise. I explained to her the difference between an author’s perspective and that of their characters. That said, O’Brien was also a product of his time, shaped by the societal conditions he lived in. It’s one of the hardest things to convey to students: we are all shaped by our environments, and who knows what actions or beliefs we take for granted today might be seen as objectionable a hundred years from now.

It’s also important to distinguish between an author and their characters, a distinction that can be challenging. Poe faced this as well; while he was a melancholic figure, he wasn’t the same as the characters he wrote about. O’Brien shared a similar situation. For instance, in his story “The Diamond Lens”, the character Linley is a despicable figure who makes anti-Semitic remarks about his neighbor, Simon, whom he eventually kills. One of my students once suggested that this made O’Brien himself anti-Semitic, which took me by surprise. I explained to her the difference between an author’s perspective and that of their characters. That said, O’Brien was also a product of his time, shaped by the societal conditions he lived in. It’s one of the hardest things to convey to students: we are all shaped by our environments, and who knows what actions or beliefs we take for granted today might be seen as objectionable a hundred years from now.

Ultimately, I believe O’Brien deserves recognition for his social, political, and economic views. He was, in many ways, a haute bohème—someone from a privileged background, despite the economic hardships he faced as an adult. That mindset never entirely left him. While I doubt he was volunteering at soup kitchens or donating to poorhouses, he brought awareness to the struggles of the marginalized through his writing. His contributions in this regard should be acknowledged, even if his activism didn’t extend beyond the page.

JK: A notable feature of O’Brien’s work is the vivid imagery he uses and his wild flights of fancy. I’m thinking particularly of “From Hand to Mouth” and “The Lost Room”, which are incredibly rich in ideas and imagery.

JPI: Absolutely, this is one of the most underestimated aspects of O’Brien’s work and a key reason why he deserves a broader and more popular reputation, both within genre fiction and mainstream literature. He was ahead of his time in both his ideas and literary techniques. For example, stories like “From Hand to Mouth” and “The Wonderful Adventures of Mr. Papplewick” are at the forefront of early surrealism. O’Brien is credited with being the first to explore the concept of invisibility in “What Was It? A Mystery” and was also among the earliest to tackle the idea of robots in “The Wondersmith”.

O’Brien had a knack for taking existing literary themes and reimagining them from new perspectives. For instance, “Broadway Bedeviled” is a pastiche of Poe’s “The Man of the Crowd”, but instead of narrating from the pursuer’s point of view, O’Brien flips the narrative to follow the perspective of the pursued. Similarly, his stories “Uncle and Nephew” and “Mezzo-Matti” play with the themes found in Poe’s “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether”. Then there are his truly unique and innovative stories, like “The Lost Room”, which I consider one of his best and my personal favorite. I believe there’s a strong case to be made that H. P. Lovecraft drew inspiration from “The Lost Room” for his story “The Music of Erich Zann”. When I mentioned this idea to S. T. Joshi, the foremost Lovecraft scholar, he found it intriguing. While there’s no definitive proof, the similarities between the two stories are striking, and we know that Lovecraft was an admirer of O’Brien.

O’Brien was an intellectual experimenter, constantly tinkering with different genres, concepts, and ideas. He took elements that worked well in the writings of others and reworked them in ways that made them distinctly his own. His creative energy was boundless, producing a diverse body of work that explored a wide range of themes. Who knows what other stories may still be out there, unattributed but potentially O’Brien’s creations?

JK: I’ve heard O’Brien referred to in some quarters as the “Irish Poe”. Do you think there’s some justification for this claim?

JPI: Yes and no. While there are notable similarities between Poe and O’Brien, their connections go beyond shared styles and influences. Both authors initially aspired to be recognized for their poetry: Poe’s first publications were poetry collections, which did not achieve much success, and O’Brien’s earliest works were also in verse, published in The Nation (Dublin). Judging O’Brien’s success is difficult, given his young age at the time, though nearly all his submissions were accepted. Both writers were heavily influenced by the Romantics and were critical of the Transcendentalists, albeit in different ways—Poe’s criticisms were direct, while O’Brien’s were more understated.

Their eventual recognition came through Gothic short stories, a genre in which they both excelled. O’Brien generally adhered to Poe’s idea that a short story should be readable in one sitting, though both did experiment with longer forms. Depression was a common struggle for them, though they dealt with it differently: O’Brien seemed to indulge in drinking, while Poe had a low tolerance for alcohol. Both came from wealthy backgrounds (Poe’s through his adoptive family), yet struggled financially throughout their lives. Their military careers were also unconventional—Poe had a brief but successful stint, including time at the U.S. Military Academy, while O’Brien served in the army. Outside of fiction, both found success in journalism and editing, despite often contentious relationships with editors and the ethical dilemmas of the literary marketplace.

As for their literary connections, O’Brien felt an intellectual kinship with Poe. The exact point when he first encountered Poe’s work is hard to pinpoint. Poe began publishing in the 1830s, and his first major success, “MS. Found in a Bottle”, appeared in 1833. Though Poe’s works were primarily published in American journals, they reached European audiences due to the lack of international copyright laws. The first known French adaptation, “James Dixon, or The Fatal Resemblance” (based on “William Wilson”), appeared in 1844, and Charles Baudelaire later became a major advocate for Poe in France. Baudelaire published a biography and analysis of Poe in 1852, which introduced the French edition of Poe’s works in 1856. If O’Brien visited France during 1848-9 on a Grand Tour, which I believe he did, he would likely have encountered Poe’s writings through these avenues, and his time in London would have provided further exposure. By the time O’Brien arrived in America in 1852, Poe’s reputation was well-established, even though Poe had been dead for nearly four years.

There were significant differences between the two as well. Poe was more self-aware as a writer, concerned with his literary legacy, and wrote extensively about the philosophy and craft of writing. O’Brien, on the other hand, was less disciplined and approached writing more as a practical endeavor. However, his ten years in America showed considerable growth as a writer, suggesting that had he lived longer, his approach might have evolved. Both died young—Poe under mysterious circumstances and O’Brien from a Civil War wound—but Poe’s influence on O’Brien’s body of work is undeniable.

JK: It’s also interesting to speculate if he would have delved a little more into science fiction if he had lived longer. Both “The Diamond Lens” and “How I Overcame My Gravity” are worthy of H. G. Wells.

JK: It’s also interesting to speculate if he would have delved a little more into science fiction if he had lived longer. Both “The Diamond Lens” and “How I Overcame My Gravity” are worthy of H. G. Wells.

JPI: It’s fascinating to consider whether O’Brien might have explored science fiction more deeply if he had lived longer. Stories like “The Diamond Lens” and “How I Overcame My Gravity” demonstrate a visionary quality that anticipates the work of H. G. Wells. In fact, I suspect that Wells may have been influenced by O’Brien, although I don’t have definitive evidence to support this beyond some striking similarities in their narratives.

The challenge with attributing influences in science fiction is that the genre itself was not clearly defined in O’Brien’s time; it wasn’t until the twentieth century that the term “science fiction” and its history began to be formally established. Some of O’Brien’s stories certainly qualify as early science fiction, while others lean toward fantasy, weird fiction, or a blend of these genres. Many of his works defy strict classification, representing hybrids of speculative and romantic elements. While about half of his short fiction falls into these speculative categories, the rest fits the romantic and sentimental styles that were popular at the time. Like many writers of his era, O’Brien had to cater to the demands of the literary marketplace to make a living. He, much like his friend Melville, often critiqued the soul-crushing nature of such work. O’Brien’s story “From Hand to Mouth” directly addresses this, and Melville’s famous tale “Bartleby, the Scrivener” can also be seen as an indictment of the dehumanizing effects of work devoid of meaning.

I sincerely hope that this new three-volume edition of O’Brien’s speculative writings, published by Swan River Press, will spark renewed interest in his work and begin to shift his reputation as a writer. O’Brien scholarship has gone through various phases, but none have truly succeeded in bringing him to a wider audience. Moreover, since the 1880s, little new material or scholarship has emerged. With these volumes, there is genuine hope that O’Brien will finally receive the recognition he deserves. I’m deeply grateful to Brian J. Showers and the team at Swan River Press for recognizing the value of this project. I also appreciate the opportunity to discuss O’Brien in this interview.

If you’d like to learn more, check out “Publishing Fitz-James-O’Brien”.

Buy the Collected Speculative Works of Fitz-James O’Brien

A reader recently asked me if Swan River Press would ever consider publishing an edition of Robert W. Chambers’s classic collection The King in Yellow (1895). While I love that book, and own multiple early editions, it didn’t take me long to form a response: No, we would not.

A reader recently asked me if Swan River Press would ever consider publishing an edition of Robert W. Chambers’s classic collection The King in Yellow (1895). While I love that book, and own multiple early editions, it didn’t take me long to form a response: No, we would not. A volume of FJOB’s work never manifested during his lifetime—although he did plan one, even going so far as to list his preferred selection (the full background of this proposed book can be found in “A Note on the Text” in the Swan River edition). Realising FJOB’s original volume was one of the ideas that John and I discussed. However, much as I like this approach (see Bram Stoker’s

A volume of FJOB’s work never manifested during his lifetime—although he did plan one, even going so far as to list his preferred selection (the full background of this proposed book can be found in “A Note on the Text” in the Swan River edition). Realising FJOB’s original volume was one of the ideas that John and I discussed. However, much as I like this approach (see Bram Stoker’s  John and I considered other possibilities for this project, but eventually settled on a rather ambitious (for SRP, at least!) three-volume set that would present FJOB’s speculative writing in chronological order. We felt this approach would best showcase FJOB’s trajectory as he developed his craft. Additionally, John unearthed a number of stories and poems that had hitherto not been reprinted since their original magazine appearances. All this would be complemented by three comprehensive introductions by John, which would in turn trace FJOB’s life and works, from his early years in Co. Cork to his wounding and eventual death from that wound during the American Civil War.

John and I considered other possibilities for this project, but eventually settled on a rather ambitious (for SRP, at least!) three-volume set that would present FJOB’s speculative writing in chronological order. We felt this approach would best showcase FJOB’s trajectory as he developed his craft. Additionally, John unearthed a number of stories and poems that had hitherto not been reprinted since their original magazine appearances. All this would be complemented by three comprehensive introductions by John, which would in turn trace FJOB’s life and works, from his early years in Co. Cork to his wounding and eventual death from that wound during the American Civil War. As you can see, we’ve worked hard to provide readers with that “something more” they’ve come to expect from Swan River Press. To my knowledge, this limited, hardback, three-volume set of the collected speculative fiction of Fitz-James O’Brien is not only the most complete collection of his work now available, but also the first Irish edition—appropriate that its official publication day is St. Patrick’s Day. And John P. Irish’s comprehensive introductions serve to guide the reader to a new understanding of Fitz-James O’Brien’s importance in the development of literature of the fantastic.

As you can see, we’ve worked hard to provide readers with that “something more” they’ve come to expect from Swan River Press. To my knowledge, this limited, hardback, three-volume set of the collected speculative fiction of Fitz-James O’Brien is not only the most complete collection of his work now available, but also the first Irish edition—appropriate that its official publication day is St. Patrick’s Day. And John P. Irish’s comprehensive introductions serve to guide the reader to a new understanding of Fitz-James O’Brien’s importance in the development of literature of the fantastic.