James Machin in Conversation with Timothy J. Jarvis

James Machin in Conversation with Timothy J. Jarvis

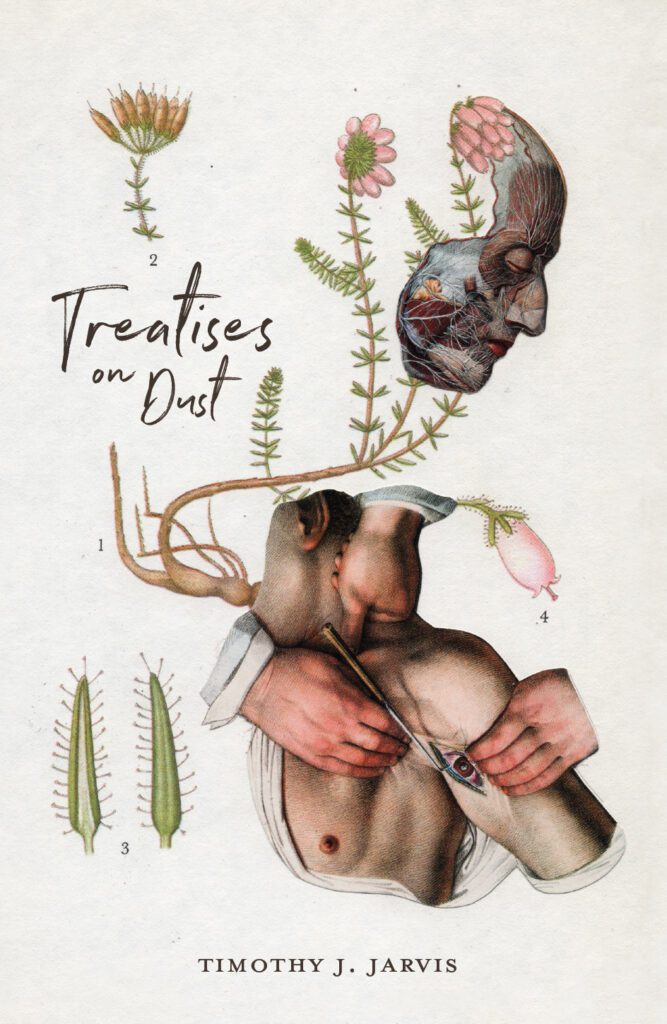

Timothy J. Jarvis and I met for this conversation in Highbury, North London, a setting he has used frequently for his fiction, to discuss his forthcoming collection Treatises on Dust. We escaped the chaos of the Friday night revel into the sedate early-evening quiet of the Mildmay Club on Newington Green to have our conversation, which came to a timely end as the jazz band was setting up.

James Machin: How was the collection put together? How did you organise the table of contents? Did you take the opportunity to rework any of the stories and add any through-line of continuity?

Timothy J. Jarvis: Definitely—I was very conscious I wanted it to be a collection with a thread. The stories already had some sort of connective tissue. I realised when I was putting it together that there were two kinds of stories I’d been working on over the last ten years or so. One strand ended up being Treatises on Dust, which has this sense of me as a character moving in and out as an observer and collecting strange tales. There’s another strand concerning an eldritch photocopier—I’ve kept those stories back. There’s one newer story—“We Recognise Our Own” (though several are original to the collection)—and I wanted there to be a mixture of longer stories and very short stories of just a page or two, which I have scattered throughout.

I did rewrite to create further connective tissue: I’d just read Keith Ridgway’s Hawthorn and Child. The best way to describe it is Derek Raymond-style occult crime, but the novel is totally fragmentary with no linear narrative—and I thought why not try and make the stories work like that—with a sense that they aggregate meaning when you put them in the context of the collection.

I did rewrite to create further connective tissue: I’d just read Keith Ridgway’s Hawthorn and Child. The best way to describe it is Derek Raymond-style occult crime, but the novel is totally fragmentary with no linear narrative—and I thought why not try and make the stories work like that—with a sense that they aggregate meaning when you put them in the context of the collection.

JM: There is that consistency of imagery; that accretion of imagery across the stories that takes on a suggestive meaning of its own.

TJJ: I admire contemporary writers such as Mark Valentine who have recurring conceits across their stories, also Laird Baron though his is more cosmic in scale—I really like that mythos thing that comes from Lovecraft and other classic weird tales writers—and I wondered what would happen if you did it, but without the cosmicism.

JM: That’s interesting because my next question was about Lovecraft—and I have a note here to the effect that though you do use Lovecraftian strategies—“pseudobiblia”, deep history, cursed art—you don’t use identifiable Lovecraftian tropes. None of these stories could work in the context of cottage-industry mythos anthologies. It’s to your credit that you don’t resort to that—a single mention of Bloch’s De Vermis Mysteriis aside.

TJJ: I guess the pseudobiblia is one of my favourite aspect of Lovecraft’s work, the use of fictional and actual occult tomes . . .

JM: Including your own Day’s Horse Descend.

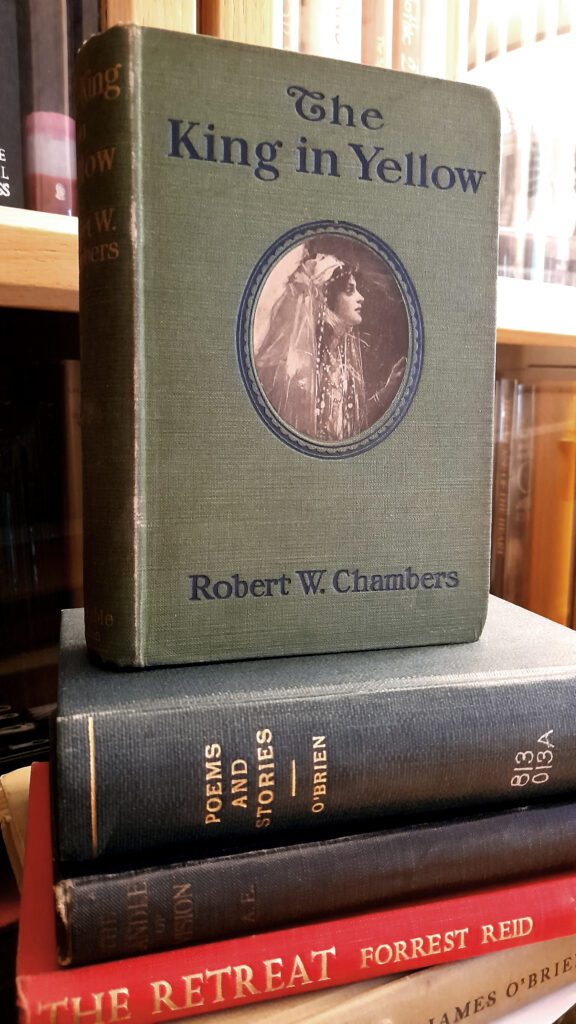

TJJ: There’s also a reference to a writer from Gary Budden’s fictional work—I use an author created by him in London Incognita in “We Recognise Our Own”. But it’s Chambers’ The King in Yellow (and by extension Bierce’s “An Inhabitant of Carcosa”, I guess) that was my real inspiration in doing that sort of thing.

TJJ: There’s also a reference to a writer from Gary Budden’s fictional work—I use an author created by him in London Incognita in “We Recognise Our Own”. But it’s Chambers’ The King in Yellow (and by extension Bierce’s “An Inhabitant of Carcosa”, I guess) that was my real inspiration in doing that sort of thing.

JM: You seem to me to be using the conceit in a much more consciously metafictional way than e.g. Lovecraft—a modernist or postmodernist way reflecting that you’re writing a century later.

TJJ: Part of that is that I like comedy, but I’m not trying to be funny—using the form of comedy but without the jokes. I don’t like earnestness, which can be the Achilles’ heel of a lot of contemporary horror and weird fiction. I like to be playful with nothing taken very seriously.

JM: I don’t think it’s not taking it seriously but rather just that lack of earnestness—maybe that word “ludic” connoting a knowing manipulation of the text.

TJJ: I think a lot of this is Walter de la Mare, actually—people telling stories to one another in restaurants or pubs . . .

JM: Yes, I have another note here: most of your stories are what John Clute would call “Club Stories”, a form that he claims “eases our suspension of disbelief during the duration of the telling . . . but surrenders the tale to the judgment of the world once it has been told”.

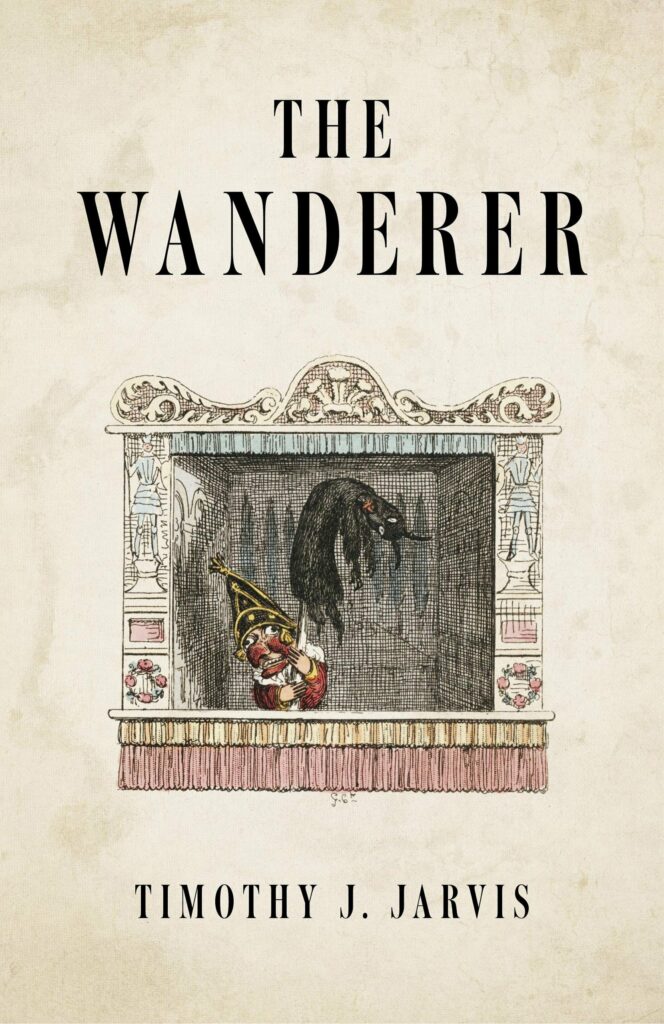

TJJ: Yes—that’s absolutely true. My novel, The Wanderer, was written and revised very much under the influence of reading Clute’s The Darkening Garden. Clute is a very important writer for me in understanding how horror works, how the Gothic works. So definitely club stories. I went to a normal primary school but the headteacher was very progressive and had this idea that you shouldn’t make children do anything they didn’t want to do—as a result I was a late starter and didn’t begin reading for leisure until I was quite old, eight or so—but then I started reading not kid’s books, but my dad’s books—he had a collection of Algernon Blackwood and J. G. Ballard and my maternal grandfather was a huge fan of golden age detective fiction, Sherlock Holmes but also Conan Doyle’s horror stories—“The Horror of the Heights” as a found document and the record of someone who’s had this encounter with an eldritch monstrosity—that style of story was a big influence on me.

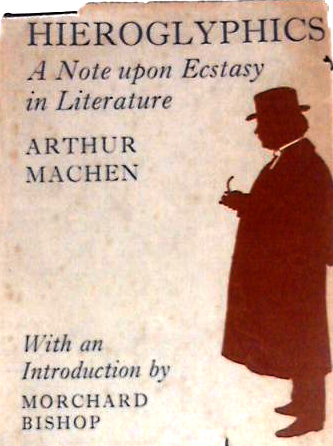

JM: And there you get the idea of the archive and found documents—the “Archive of Dread”, as Robert Lloyd Parry is calling his new show. There’s also a lot of Machen in there, as well as Dunsany—there is an explicit homage to Dunsany in one of the stories. However, in terms of genre (whether the weird or horror or Gothic), you’re not shy about throwing in really horrible, bloody gore and putrefaction—though not typical horror violence.

JM: And there you get the idea of the archive and found documents—the “Archive of Dread”, as Robert Lloyd Parry is calling his new show. There’s also a lot of Machen in there, as well as Dunsany—there is an explicit homage to Dunsany in one of the stories. However, in terms of genre (whether the weird or horror or Gothic), you’re not shy about throwing in really horrible, bloody gore and putrefaction—though not typical horror violence.

TJJ: I do really like splatterpunk as a genre. One of my favourite novels in the mode is Kathe Koja’s The Cypher, which blew my mind when I read it. That sense of the grotesque is really important to me. While people talk approvingly about the subtlety of weird or strange fiction, if you actually read, for example, Aickman’s “Ravissante”, it’s utterly grotesque, sexualised grotesque.

JM: The same goes for Machen. So you’re not trying to write “quiet” horror . . .

TJJ: I’m not really trying to write horror at all. There are extraordinary writers who define themselves as horror writers, but in general, it doesn’t interest me.

JM: It’s also a very mutable term: Ramsey Campbell will say that he’s happy to call himself a horror writer because it’s a very broad umbrella and only a snob would be squeamish about describing themselves as such—but obviously most people think about horror a bit reductively as a set of tropes, tropes that you’re not really using at all.

TJJ: I totally get that thing about snobbery and think Campbell elevates the form, but in general I think a genre is something you just burrow out of. That’s the M. John Harrison thing—you tunnel your way out of something. But then there’s no way of articulating what one wants to articulate without tropes—there’s a hair’s breadth between tropes and archetypes. Tropes aren’t bad things—tropes are tropes not because they’re commercially useful, or not only—but because they come from the collective unconscious.

JM: Which brings me on very neatly to the question of decadence and symbolism in general. Throughout the book there is a consistent use of a sort of symbolist narrative; an episodic series of incidents that turn into a dream or vision quest, which reminds me of some of the alchemical literature where the protagonist experiences a series of trials or encounters which the reader suspects are embedded in this deep web of symbolism—whether Jungian or alchemical—and the story is just the tip of an iceberg, with the main, submerged body of the iceberg being the resonances that that symbolism creates. Not that I’m suggesting this is all very carefully worked out—

TJJ: It’s 100% not carefully worked out—it’s all surface.

JM: Which is where the decadence and Aestheticism comes in . . .

TJJ: Yes—everything is surface and there’s no deeper meaning to anything. The process of composition is not to censor myself but also not to particularly think—to avoiding getting intellectual.

JM: I’ve previously heard you speak admiringly of Aickman’s writing practice, of entering a sort of ‘flow state’ of experiencing the story unfolding rather than actively constructing it.

TJJ: Either I don’t remember my dreams or I don’t dream—for me, the act of writing fiction performs the function of dreams for most people. I actually need to sit down at the laptop in order to undertake that necessary psychological process.

TJJ: Either I don’t remember my dreams or I don’t dream—for me, the act of writing fiction performs the function of dreams for most people. I actually need to sit down at the laptop in order to undertake that necessary psychological process.

JM: I always think of dreams as performing the same function as when you put your computer into defrag mode to sort the data on your hard drive.

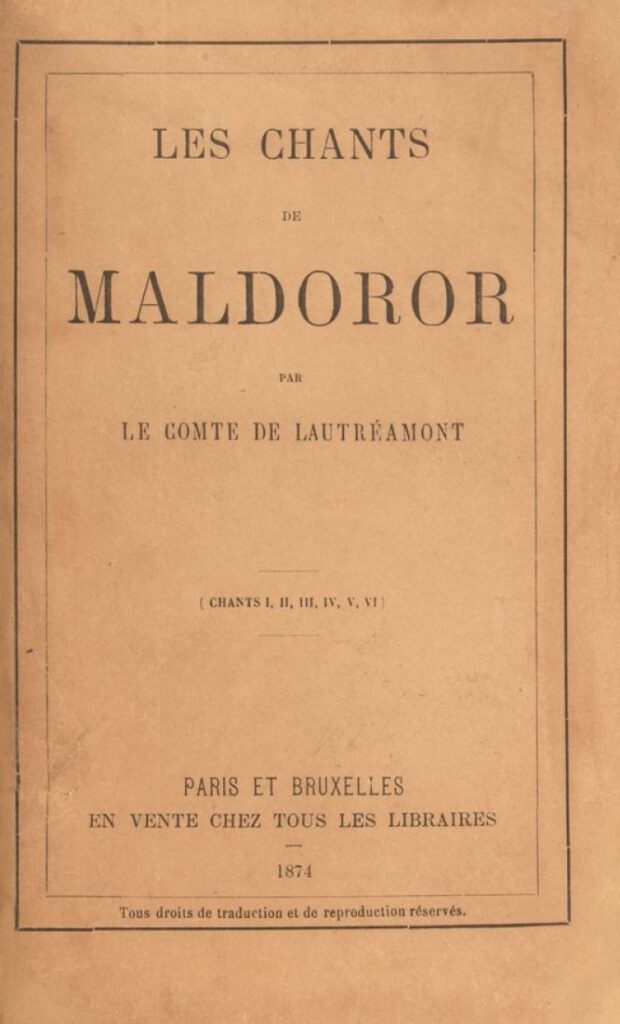

TJJ: I wonder if that’s it—and I have to do that by writing short stories. The first thing I did was a novel and I was much more drawn to novels at the time—but short stories are much more effective in sorting out the clutter of the unconscious. But going back to the symbolism stuff—that aspect of my writing likely wouldn’t exist if I hadn’t have read Comte de Lautréamont. The idea that he died at 23 or 24 and produced this thing, Les Chants de Maldoror . . .

JM: They had too much time on their hands. No TV or social media.

TJJ: He supposedly wrote at night while bashing out discords on his piano in his Parisian garret—that’s what I aspire to. I would love to be Alfred Jarry painting myself green and cycling through Paris out of my mind, well in some way, anyhow.

JM: But that is another angle—because I know you like all that Eastern European absurdist stuff (Grabiński and Schulz and so on) and the surrealism of Leonora Carrington, so that’s all there as well, in the mix.

TJJ: I have to acknowledge Dan Watt (D. P. Watt)—I don’t think I’d write like I do unless I’d read and got to know Dan, because I think he’s an extraordinary stylist, and very much informed my interest in the absurd.

JM: But isn’t that also Aickman as well? When I first put down “The Cicerones”, the first of his stories I read, I can remember feeling very short changed and exasperated. “This doesn’t make any sense!” But then I was haunted by it for weeks.

TJJ: The thing about Aickman is that to get him properly, you do have to understand the British class system. I’m sure I’d have actually liked him despite despising 90% of the things he stood for. But that is also what I like about pubs.

JM: They are a great leveller, a space where you can escape the class system?

TJJ: My grandparents on the maternal side of the family were upper middle class, quite aspirational—my grandfather was a judge—but on my dad’s side they were working class, manual workers, my grandmother came over from Ireland as a teenager to work as a maid in a big house. In terms of British society, this makes me feel quite liminal. The idea of the pub as a liminal space really interests me.

JM: Which also ties into geography—I know it’s where you live and have worked but also Bedford and Luton—they’re a liminal region in terms of class, demographics, spaces between rural and urban, within the purlieu of London but not London, nor Midlands really—though home to John Bunyan who wrote a very famous vision quest full of encounters with strange entities.

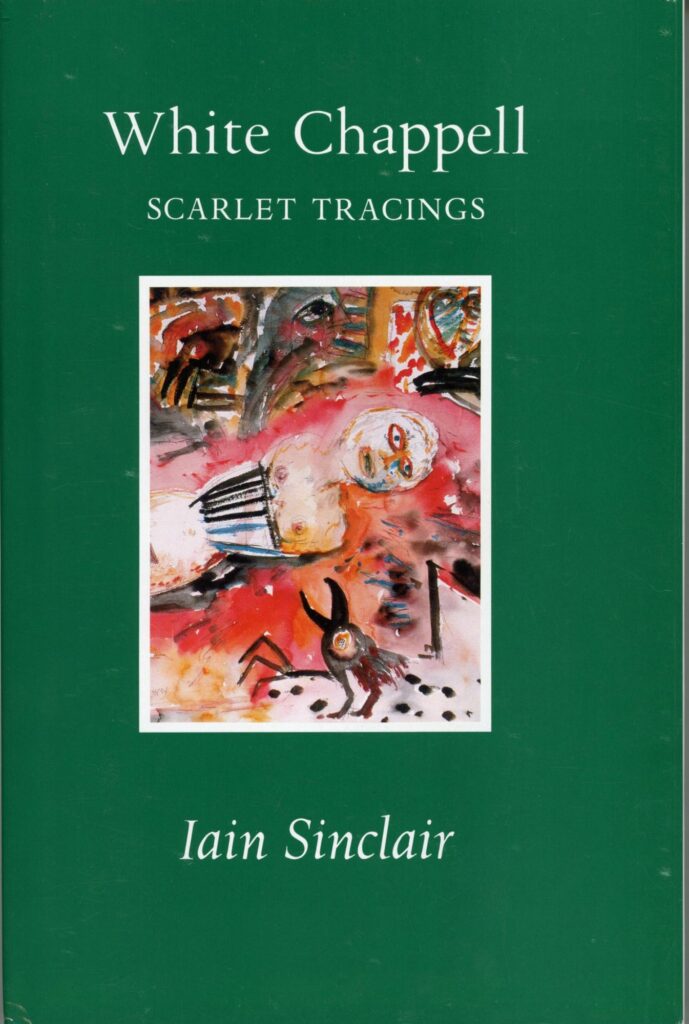

TJJ: Living in Bedford and working in Luton was really important for the collection. The pub in Luton which is in a couple of the stories—the Bricklayers Arms—is a real place. My dad’s side of the family are from Luton and I grew up in Bedford. When I moved to London I was very into Iain Sinclair, Machen, and the psychogeography of London and its storied legacy. I moved back to Bedford for work and wanted to think about how that sort of writing would work in that context.

TJJ: Living in Bedford and working in Luton was really important for the collection. The pub in Luton which is in a couple of the stories—the Bricklayers Arms—is a real place. My dad’s side of the family are from Luton and I grew up in Bedford. When I moved to London I was very into Iain Sinclair, Machen, and the psychogeography of London and its storied legacy. I moved back to Bedford for work and wanted to think about how that sort of writing would work in that context.

JM: You’re not celebrating the great storied metropolis but neither are you wallowing in misery or being resolutely downbeat.

TJJ: No, I’m not doing that and that’s not my conception of Luton and the people of Luton. When a few years’ ago the far right tried to foment trouble in Luton they were totally rejected by the community, who were horrified. Because that’s not what Luton is. It has its political and economic struggles, but it’s still hopeful and lively and resilient. That particular pub, the Bricklayers, is a really vibrant place. What I love about pubs is that people can cross those class boundaries. I genuinely love that pub, and that community.

JM: You deal with some social realities but there’s no sense that you’re being a tourist in misery—it’s far more nuanced. For example, the relationship between the Bulgarian immigrant seasonal worker and the elderly, bohemian artist in “With Scourges, with Flowering Sprigs”: it’s easy to imagine such a relationship emerging in a pub, facilitated by alcohol.

TJJ: Yes, that sense of boundaries being crossed—or rending the veil even. Every small town will have the usual chain places, but also one or two pubs that will really facilitate that liminality.

JM: I grew up in a small village in Kent and the village pub was exactly like that; a suspension of the everyday. My experience of bars in America is that they seem almost set up to be sleazy, with blacked-out windows and so on. It’s like you’re doing something sketchy by even walking into one.

TJJ: It’s probably literally the only thing about Britain I like—British pub culture.

JM: Not that anything in your book could be considered social realism. With, for example, “And Yet Speaketh”, even though it starts with the mundane situation of two academics having a drink in a pub, you’re not trying to convince the reader that it’s “real”. It’s clear from the outset that it is a fiction, with sixteenth-century doggerel appearing in unlikely places, etc.

TJJ: M. John Harrison is the lodestar for me in this respect. I really love the way he produces a sense of the real that is always riven with the sense of strangeness. I don’t have the chops to do that, so I work within my limitations. In some ways the writer that I’m always working through is Burroughs, particularly his “Western Lands” trilogy, but also the stories in Exterminator!, where you wonder if this is just someone working in bug control in New York and why the whole thing is riven by such strangeness. I aspire to use those same gestures and the conventional literary realist pursuit of subtle character and convincing situations leaves me cold.

JM: Yes, so in terms of the conversations people have in your stories, they’re not realistic conversations. It’s the opposite of naturalistic and very intentionally so . . .

JM: Yes, so in terms of the conversations people have in your stories, they’re not realistic conversations. It’s the opposite of naturalistic and very intentionally so . . .

TJJ: Yes, it’s very deliberate—that’s again the influence of Walter de la Mare, with his staginess. I don’t believe in the real, so the idea of mimesis—that technique where you give the reader a mimetic reality and then undercut it—I’m not interested in that. This is very much the Machen “ecstasy” thing—I’m more interested in the fictional representation of the rending of the veil rather than concerned about whether that could actually be a thing. Not to denigrate Stephen King, who in many ways is a remarkable writer, but I’m not interested in the King thing of “here’s the convincing Maine town and the lives of all these nice blue collar people, but then . . . ”

JM: . . . the idea of the horror story being the irruption of horror into “reality”.

TJJ: Yes, because that suggests that there is evil and that it can be overcome and I don’t believe in either of those things.

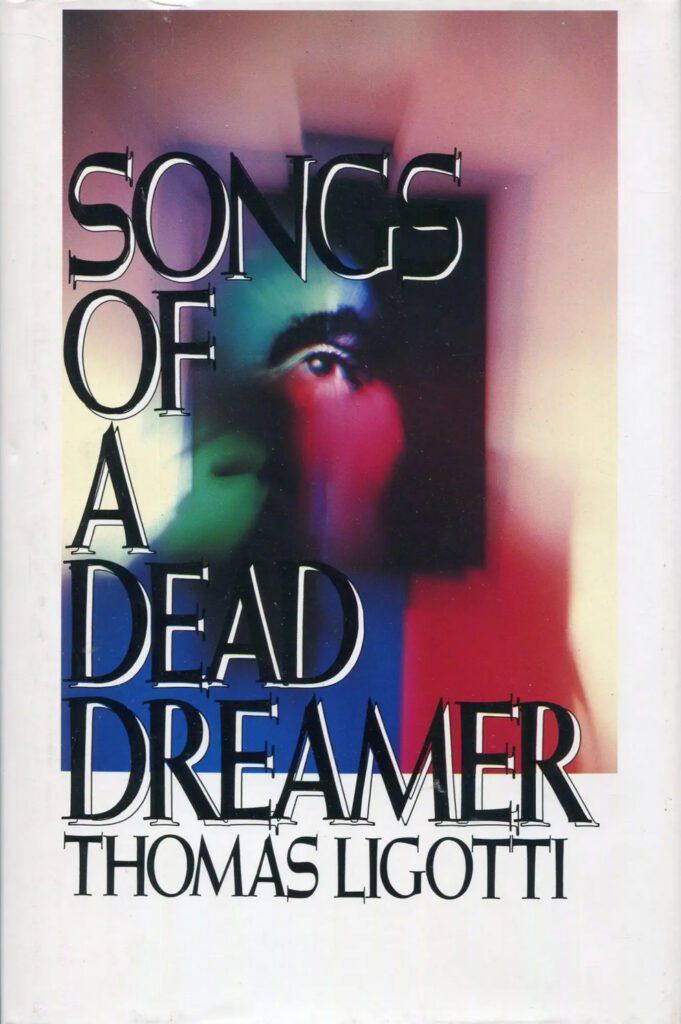

JM: My reading is that this isn’t philosophical horror, after Ligotti, for example. Though it is Ligottian in places, there doesn’t seem to be a parsable “message” or philosophical underpinning—what’s going on seems to be more aesthetic and symbolist.

TJJ: I love Ligotti and consider him one of the most important writers of the last forty years—but I’m not a pessimist and I don’t hold with the pessimistic worldview. I think life is generally pretty good, but I think it usually lacks transcendence and ecstasy.

JM: And that’s all aesthetics—and that’s not to undervalue the aesthetic. I think there’s often a misapprehension that aesthetics are somehow superficial, but I think that’s wrong: in the face of a meaningless cosmos, aesthetics is everything, it’s the meaning-producing machine.

TJJ: I always come back to Marcel Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even”: there’s a machine, there’s a chaotic cloud, it’s weird, but it’s formal and it’s structuralist. I’m not keen on Lovecraft’s notion of aesthetics giving order to chaos—why does he hate the mad piping?

JM: But I don’t think that’s quite right re. Lovecraft, because as his own stories demonstrate, what he really likes is an ecstatic chaos because that’s all he writes about. He loves the mad piping!

TJJ: Nietzsche’s thing about blending the Apollonian and the Dionysian—I think the Apollonian stuff is no good and we don’t need it.

JM: Though it is also why we have the wherewithal to eat and live somewhere under shelter.

TJJ: I think it’s probably better to starve and live in chaos isn’t it? Machen thought so.

JM: But he lived such a High-Tory bourgeois life.

JM: But he lived such a High-Tory bourgeois life.

TJJ: Which involved a lot of drinking.

JM: Which is Dionysian. To change the subject to specific imagery: why the lists of animals—of fauna and flora too, actually? I was reminded of “The Goblin Market”. Together with the references to the “interconnectedness” of things, I wonder whether this is a source of horror, the teeming world-without-us.

TJJ: I love “Goblin Market”—and both Rossettis have a presence in the collection, and Swinburne too, and the mid-Victorian mood in general. But again, the animals come from Lautréamont: he plagiarised and cut in excerpts from natural history works into his text. At one point there’s this list of various creatures taking over Maldoror’s body—a viper eats his penis and takes its place, a crab holds his anus shut with its claw . . .

JM: Roosters, bulls, nightjars, apes—is it “eco-Gothic”?

TJJ: The last story, how I wanted the collection to end, is with the focus on the affect of loss.

JM: Hence all the disappearances.

TJJ: Yes, and the disappearance that affects me most is the disappearance of the natural world. I wouldn’t necessarily want to write climate change fiction, but the affect of loss is something I want to convey. And the last story is meant to be a very surrealistic post-Apocalypse.

JM: Which is also created in The Wanderer.

TJJ: I’m not a nihilist—I despise some individual people but think humanity as a whole is great . . .

JM: Most people say the opposite.

TJJ: Yes, the thing is that I don’t believe in evil; I’m interested in the affect of ecstasy and the affect of loss.

TJJ: Yes, the thing is that I don’t believe in evil; I’m interested in the affect of ecstasy and the affect of loss.

JM: The preoccupation with artists and writers disappearing is also quite Ligottian.

TJJ: I couldn’t get “The Bungalow House” out of my head. But also the idea that a lost nineteenth-century decadent poet could somehow have this big, persistent influence . . . Ligotti writes a lot about visual artists, but for me literature is the most important artform.

JM: So you have a hierarchy—“all art aspires to the condition of literature, even music”, to misquote Walter Pater?

TJJ: Literature isn’t abstract, but neither is it conceptual, it’s not purely affectual—the connection between literature and magical practice is indicative of this; most notions of magic involve the repetition of magical formula.

JM: That’s the Alan Moore thing: grimoire/grammar; spells/spelling . . .

TJJ: I think words can crowbar open things that images and sounds can’t. So I genuinely think that there is a hierarchy of aesthetic affect and I think that literature is at the top of that tree.

Buy a copy of Treatises on Dust.

James Machin is an editor, teacher, and writer who lives in London. Recent books include British Weird: Selected Short Fiction, 1893–1937 for Handheld Press and his short fiction has been published in Supernatural Tales, The Shadow Booth, and Weirdbook. Together with Timothy J. Jarvis and Sam Kunkel, he is co-editor of Faunus: the journal of the Friends of Arthur Machen.

No Comments yet!