A Flowering Wound

John Howard

Availability: In Print – Hardback, In Print – Paperback

“It was only in my dearly loved evenings that I still felt at home.” – Joseph Roth

Two of the stories in this collection by John Howard have their setting in a certain west London suburb—the calm prospect of its small houses and tree-lined roads is deceptive. And throughout this selection of stories, whether in outer London or hyperinflationary Berlin, Romania in the febrile 1930s, or the austerity Britain of recent years, we encounter people who live on the peripheries of their cities and societies—and at the edge of their own lives and illusions. They might think they know the rules, but it often turns out they do not, after all. Or perhaps the rules changed—silently, abruptly. In these stories past and present come together with wounding consequences for those caught out by the system—or its absence.

Hardback edition limited to 350 copies.

Cover art by Jazon Zerrillo

ISBN: 978-1-78380-027-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-78380-777-2 (pbk)

Contents

“A Glimpse of the City”

“Portrait in an Unfaded Photograph”

“The Golden Mile”

“Falling into Stone”

“Ziegler Against the World”

“A Flowering Wound”

“We, the Rescued”

“The Man Ahead”

“Twilight of the Airships”

“Under the Sun”

“Acknowledgements”

John Howard

John Howard was born in London. His books include The Silver Voices, Written by Daylight, Buried Shadows, A Flowering Wound, and The Voice of the Air. With Mark Valentine has written the joint collections Secret Europe, Inner Europe, Powers and Presences, and This World and That Other. His stories have appeared in many anthologies. He has published essays on various aspects of the science fiction and horror fields, including such iconic authors as Fritz Leiber, Arthur Machen, and August Derleth. He has also written about many now lesser-known and unfairly obscure authors and their work.

Read more“John Howard’s tales seemed to me like suitable summer reading. Many of the stories concern overlit urban landscapes not unlike those in the stories of J. G. Ballard, though the mood is very different . . . . There are also some stories that recall Arthur Machen’s approach to London, his insistence that the great metropolis is a place of magic and mystery.” – Supernatural Tales

“Luscious and lovely in appearance, of course, and full of haunting stories of love and confusion . . . a thoughtful collection of London and Europe-based fiction, a very suitable accompaniment to these terrifying times.” – A Ghostly Company

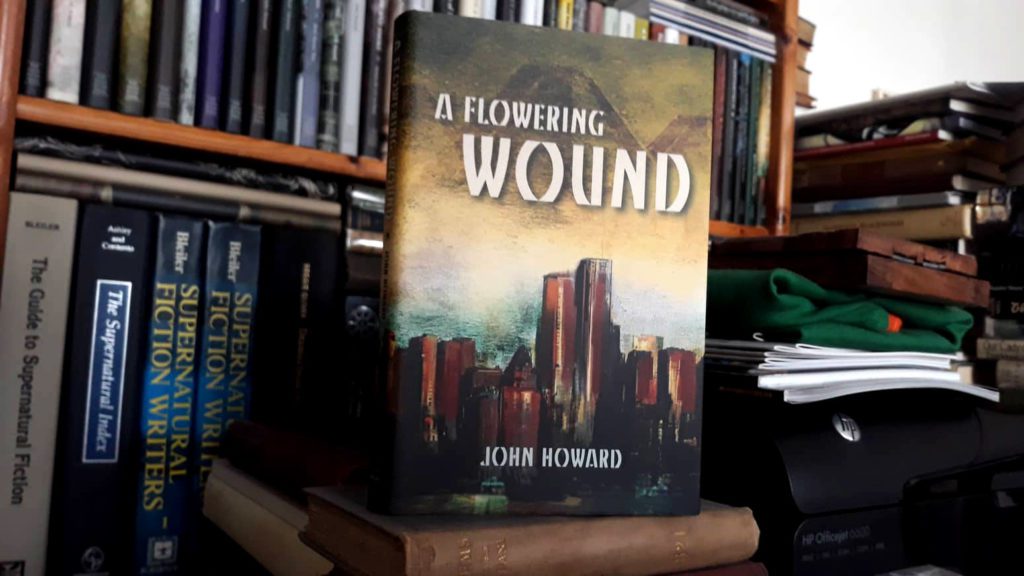

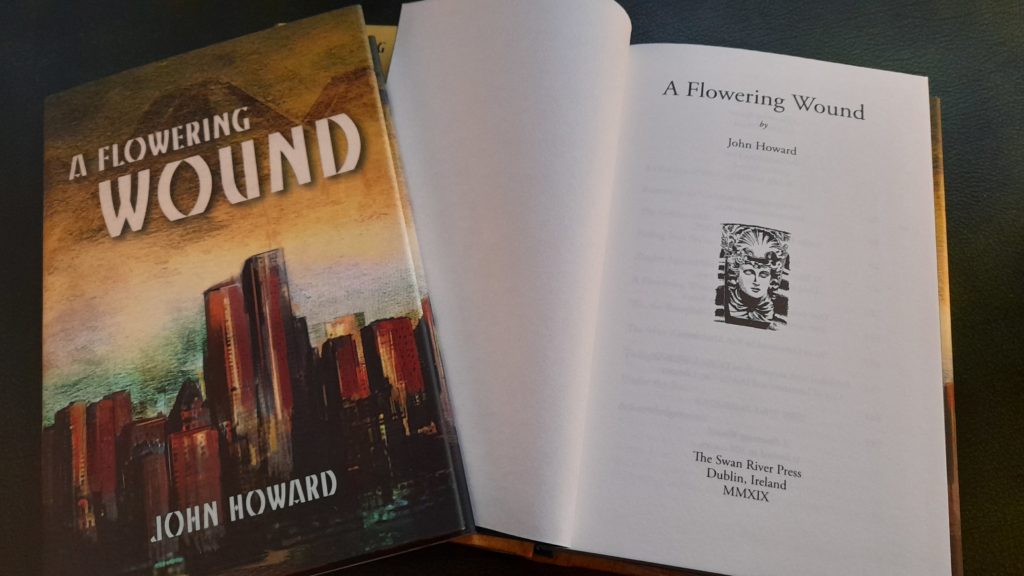

A Flowering Wound by John Howard. Cover art by Jason Zerrillo; jacket design by Meggan Kehrli; edited by Brian J. Showers; copyedited by Jim Rockhill; typeset by Ken Mackenzie; published by Swan River Press.

Hardback: Published on 15 July 2019; limited to 300 copies of which 100 are embossed and hand numbered; 181 pages; lithographically printed on 80 gsm paper; dust jacketed; illustrated boards; sewn binding; head- and tail-bands; ISBN: 978-1-78380-027-8.

Paperback Edition: Published on 30 June 2024; no limitation; print on demand; 189 pages; digitally printed on 80 gsm cream paper; perfect bound; ISBN: 978-1-78380-777-2.

“An Interview with John Howard”

“An Interview with John Howard”

Conducted by Florence Sunnen, © July 2019

Florence Sunnen: Although the stories in A Flowering Wound are consistent in tone and sensibility, your writing is difficult to pin down to a genre. How do you find your writing categorised most often, and how do you feel about these categories?

John Howard: As an unashamed long-time reader of genre fiction (especially science fiction) I’ve never had a problem with being identified with genre. But yes, as you say—which ones, if any? I think most of my work has appeared in places which are clearly genre, but which don’t worry overmuch about exact labels. I suspect my stories are most often characterised as supernatural, fantastic, strange, weird, dark fantasy, horror (and once or twice as sf). I like Robert Aickman’s term “strange stories”—but I’m not bothered by these or any other labels, because that’s all they are. As a reader I know that I want first a good story, and if it’s genre I tend not to feel the need to over-analyse and trouble myself about further subdivisions.

FS: The uncanny often crops up in this collection as a sort of sensory haunting; in “We, the Rescued”, for instance, the protagonist experiences a romance gone wrong as bouts of unseasonal heat. Is the sometimes inexplicable misfiring of the sensory apparatus something that unsettles you?

JH: Yes, I’m sure it would unsettle me a hell of a lot—and if me, then others. However, I think the main impetus behind the heat was that I wrote the story in the depths of winter and was trying to imagine myself warm! As I get older I find extremes of temperature more and more tiresome to have to cope with, even if unavoidable. When it’s hot I get lethargic and want to lie down and sleep; when it’s very cold I want to go to bed!

FS: Do you feel affected by ghost stories? Is there a ghost story (or uncanny story) you have encountered recently that particularly resonated with you?

JH: I don’t find the term “ghost story” very helpful. For me the term is too restrictive—or vague. But yes, a good ghost story (or uncanny story, a much more helpful term) will always be welcome. For a start I try to keep refreshed in the classics: the best of the likes of Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, H. P. Lovecraft, J. Sheridan Le Fanu, Fritz Leiber, Robert Aickman, both Jameses (M. R. and Henry), Thomas Ligotti, Charles L. Grant, Clark Ashton Smith, and so on and on.

Recently I re-read Machen’s The Three Impostors, which always gives me a kick (although usually a different one each time). Inspired by James Machin’s recent book on weird fiction in Britain I’ve been reading my way through John Buchan’s uncanny stories, many of which I’d heard of for years but never read—such fine tales as “The Wind in the Portico” and “Skule Skerry”. I’ve read Francis Brett Young’s Cold Harbour (1924) and To Walk the Night by William Sloane (1937) several times each over the decades, and their chill and subtle otherness has never let me down.

Current writers whose new collections and novels go straight on the to-read pile include Christopher Priest, Nina Allan, Peter Straub, Rosalie Parker, R. B. Russell, Steve Rasnic Tem, Mark Valentine, and Colin Insole. Mark Valentine is one of my oldest friends (and we have collaborated on several stories) so I might be biased, but I think his story “The Fig Garden” is one of the finest evocations of the strange and numinous that I’ve read in years. Stephen Jones reprinted it in his Best New Horror #28, so I’m not alone!

FS: Longing to the point of obsession seems to be a theme in a number of your stories. I’m thinking here of “A Glimpse of the City” and “Ziegler Against the World” where protagonists fall prey to obsessive delusion which lapses into haunting. What does it take to write about obsession, be it with another person, a pattern, an object, or with an action that must be performed?

JH: I think you’re right in noting the recurring themes of longing and obsession. I suppose what it takes to write about them must come from the writer’s personality (however it was shaped, and continues to be). I know that if I am particularly interested in something or someone, then I want to know as much as possible about it or them. I have a strong collecting instinct, and like to seek out and gather things I’m interested in (or obsessed by). Unfortunately for my bank balance and shelf space this applies especially to books by authors I admire!

It seems to me that action is a good way of helping to secure memory. If you meet someone and have a good time, the place is important, and returning there could help to ensure it happened again.

Near where I live there’s a short road lined on both sides with trees which meet overhead, so when the trees are in leaf there’s a tunnel effect. One August evening I was walking past the end of that road. The low angle of the sunlight, the glow of the sky and cloud effects, the shadowy interior of the “tunnel” all went to create a marvellous effect. I experienced what Lovecraft called “adventurous expectancy” and I had to detour for a few minutes and walk along the road under the trees. Then I came to make a sort of ritual of it and went out for a walk at the same time each evening for a week or so in order to try and relive the experience again. And every year since, at about the right time, I’ve done the same. Of course, I never have quite relived those feelings—but it doesn’t matter. And I’ve seen many new things too: you never know what you might come across while out walking in an ordinary suburb!

FS: Do you apply a similar ritual to your writing process? Do you try to write in the same place when working on a story, or are you one of those lucky people who can immerse themselves in their stories no matter where they are?

JH: I get story ideas at any time or anywhere. When I’m working on a story, I often get ideas for plot developments, dialogue, and even endings at the most inopportune times—for example while I’m walking to work. When I get there I have to go straight to my desk and jot things down.

Otherwise, in order to actually get on with producing a story, I find it best to attempt to be disciplined and try to be in front of my laptop at home at roughly same time each evening. If I can write five hundred words or more between about nine and eleven then I’m pleased. It’s the same when I’m revising a story.

FS: In stories like “Portrait in an Unfaded Photograph” and “Twilight of the Airships”, how do you approach story research, especially when they have a particular historical setting? Do you base your research around this, or do the story ideas come to you while researching?

JH: With “Portrait in an Unfaded Photograph”, as that was written for submission to a theme anthology (a tribute to Gustav Meyrink) the extent of my research was to read up on details of his life, looking for any odd or interesting happenings, anecdotes, etc that I could then hang a story on. Thank you, Wikipedia! I think I also did a little research on settings while writing the story – but only to ensure that basic details were right. I was writing a story rather than a travelogue.

“Twilight of the Airships” was set in my fictional town of Steaua de Munte. Since I am its creator, as far as the setting was concerned I didn’t really have any research to do! I just did the usual thing of trying to ensure consistency. So the railway station is always on the north side of the river, Castle Hill is to the east of the town centre, Bruckenthal Square is located in the New Town and not the old walled town, and so on. Early on I drew a basic sketch map showing the river, the major streets, the railway etc. That helps me to maintain consistency, but doesn’t prevent me from adding things and places as and when I think of them.

I have read quite a bit of Romanian history, so when I write I am confident about the background—but when necessary I always double-check dates and the chronology of events. I read up a little on the airship programmes of Germany and the Soviet Union, but as my airships were made-up I did pretty much as I liked. I have been fascinated by the colossal rigid airships of the interwar years since childhood, and was glad to be able to use them in a story.

I’m somewhat wary of research. I think it can be used as a tactic, an excuse, for not getting on and writing the story. So I tend to jump in and get started after minimal (if any) research. I will check facts as I go (as I think I need to) or as part of the revision process. Most times when I begin a story I’m not at all sure how it will end. I trust that the ideas will continue to come.

FS: How important is visual thinking to your writing process? Do you imagine scenes in visual terms, rather than through language?

JH: The visual is highly important. In the first instance at least, a scene or incident or object often comes to mind visually, as a sort of mental snapshot or film clip, and I then have to try to use and build around it in terms of language.

FS: Do you prefer writing about cities and places with which you are very familiar (such as Berlin, in the case of this collection), or places you’ve only come into passing contact with, and whose description makes more demands on your writerly imagination?

JH: If I’m writing about real places, I tend to prefer those I’m familiar with (or think I am). If I’m using a certain location there may well be facts to get right – for example, St. Paul’s Cathedral has a dome, not a spire—and I dread making factual errors. Otherwise it’s a case of writing in general terms—letting the imagination run free. Not making any definite “commitments”, but just the intention to create a sense of a real and definite place.

As a reader, if someone writes a story set in a city I don’t know, or hardly know, as long as it feels right, they’re safe from me. But if I spot an error, that will throw me off-balance for a moment, and I’d be wondering why the author didn’t do a little more research or double-check what they thought they already knew.

FS: Which are your favourite cities to write about? Are they the same as your favourite cities to be in?

JH: I’ve set many stories in London and Berlinand I’m sure I will continue to do so. London will always be first in my heart, if I can put it that way! And I like being there: I know my way around, speak the language(!) and understand the Tube. I feel at home in London.

In many ways Berlin reminds me of London. It’s a collection of separate places grown and stuck together, it sprawls, a river runs through it, it has a train system with a colourful map as complex as the Tube (but which is really quite simple to use). It’s been some years since I was last there, so even though English is widely spoken I’d want to hope that my German would return!

Steaua de Munte is largely based on aspects of Sibiu and Sighișoara, and those are two cities which, together with Bucharest, made a strong impression on me. Unfortunately time in them was limited, so I was not able to see and explore very much. I would love to return and linger in all three.

Otherwise, unfortunately, I’m not at all well-travelled. In England my favourite cities to be in are places such as Liverpool, Lincoln, Norwich, Oxford, Shrewsbury . . . In particular, Liverpool is always a pleasure to go to. It’s lively and refreshing, and its setting is magnificent.

FS: The stories in A Flowering Wound all amble along a similar path, one evocative of loneli-ness, difficult communication, sensory distortion, and obsession (with buildings, with people, with patterns). Do you feel that the first and last stories are start and end points of a journey, spanning several decades and countries?

JH: I feel that publishers and editors are better than I am at discerning links and themes. Readers too. The publisher suggested that those particular stories lead-off and conclude the book, and I was happy to agree. I think the notion of reading a collection of stories as also being a journey is a valid one—and am glad that in this instance particular stories helped to create and sustain that idea.

Florence Sunnen was born in Luxembourg City and has lived and studied in Germany and the UK. Her academic background is in philosophy and creative writing. Her stories and collages have appeared in The Learned Pig, Mud Season Review, a glimpse of, Datableed, and Brixton Review of Books. Her story “The Hook” was published by Nightjar Press in 2018. She blogs at interiordasein.wordpress.com.