“Editor’s Note #24”

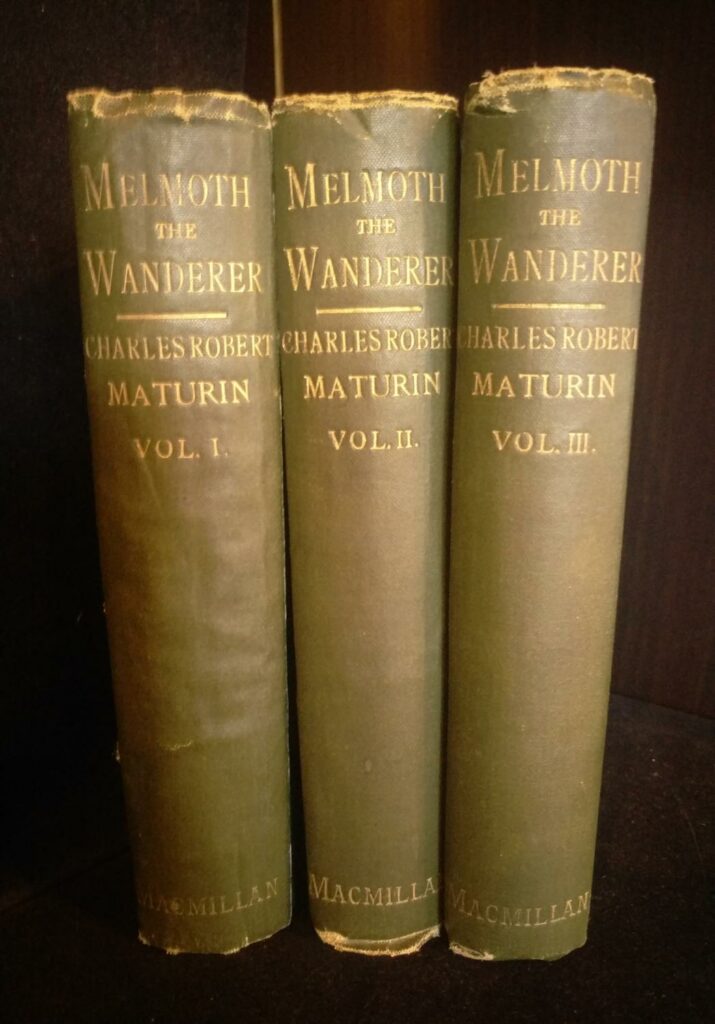

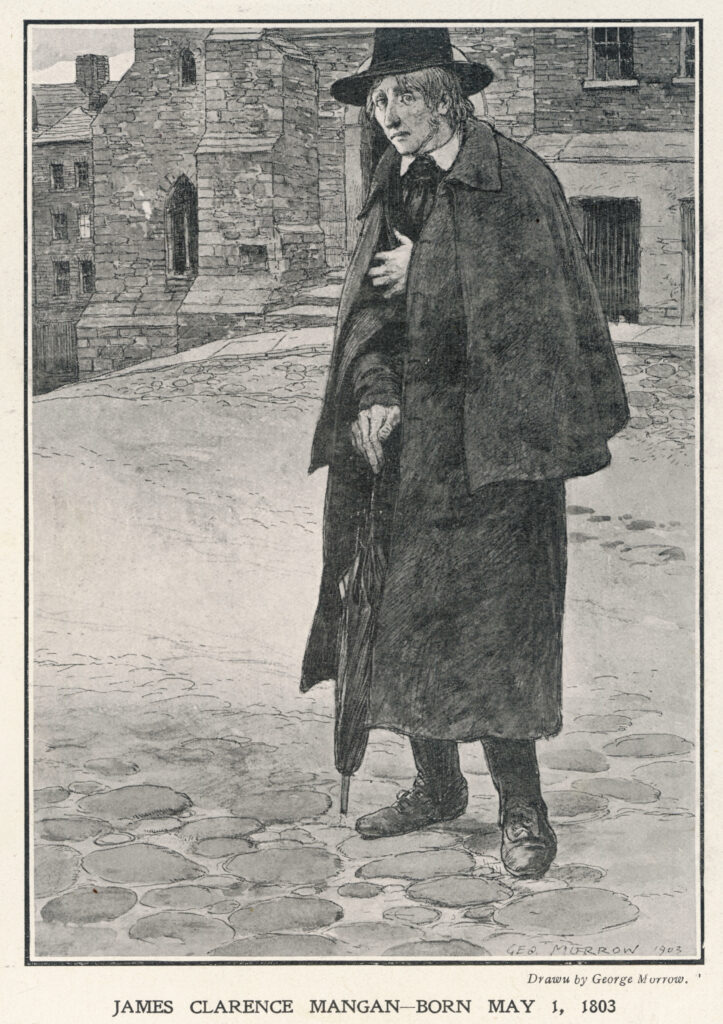

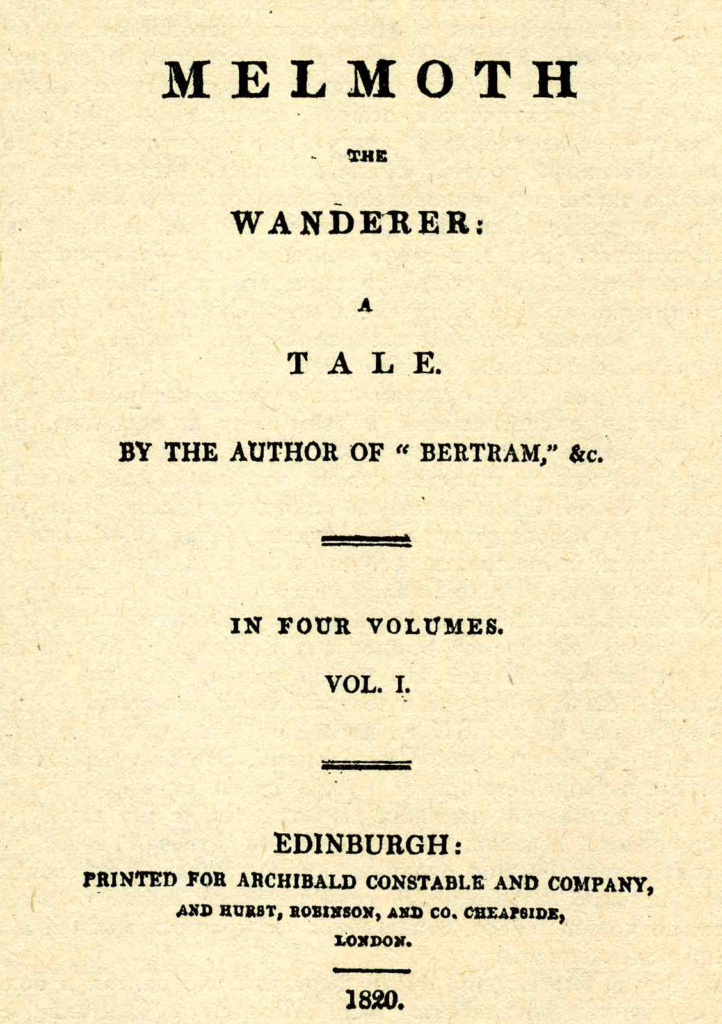

In Issue 23 of The Green Book we featured a sketch of Charles Maturin (1782-1824) penned by James Clarence Mangan, originally published in March 1849. Although we now celebrate Maturin as the author of Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), Mangan identified The Milesian Chief (1812) as his own favourite novel: “the grandest of all Maturin’s productions”. In that essay, Mangan also muses on Maturin’s underappreciated legacy in his native Dublin—“not forgotten because he had never been thought about”. He goes on tell us that the writer William Godwin wished to make a pilgrimage to Maturin’s grave, but Mangan observes, “where the remains of my distinguished countryman repose, I confess I know not”.

The answer to that question in 1849 would have been simple: the churchyard of St. Peter’s on Aungier Street, where Maturin once served as curate. The answer to that same question in 2024, as we approach the bicentenary of Maturin’s death on 30 October, is substantially more complex: St. Peter’s was razed in 1980, the churchyard and its contents removed to make way for urban development. And so what of Maturin’s admirers who, like Mangan, would make that pilgrimage to the Gothic eccentric’s final resting place? Thankfully, opening this issue we have Fergal O’Reilly’s exploration of this literary mystery, taking us on a posthumous odyssey from Aungier Street to various churches and churchyards across Dublin, by way of various archaeological reports, in search of Maturin’s earthly remains—a puzzle worthy of Yeats’s own skeletal jumble. Readers interested in learning more about Charles Maturin will find a full biographical profile written by Albert Power in Issue 12.

In keeping with the forgotten and overlooked, we have another crop of profiles from our “Guide to Irish Writers of the Fantastic and Supernatural” series, although it strikes me that many of these names will hopefully be familiar to most: Maria Edgeworth, Katharine Tynan, and Dorothy Macardle; these writers do, however, rub shoulders with the truly lesser known likes of Filson Young, Shaw Desmond, and Martin Waddell. As always, I hope you will discover new literary paths to explore with these new entries.

In keeping with the forgotten and overlooked, we have another crop of profiles from our “Guide to Irish Writers of the Fantastic and Supernatural” series, although it strikes me that many of these names will hopefully be familiar to most: Maria Edgeworth, Katharine Tynan, and Dorothy Macardle; these writers do, however, rub shoulders with the truly lesser known likes of Filson Young, Shaw Desmond, and Martin Waddell. As always, I hope you will discover new literary paths to explore with these new entries.

And finally, Bernice M. Murphy weighs in on the freshly restored and re-released Irish “folk horror” film The Outcasts (1982), written and directed by Robert Wynne-Simmons—a name some will recognise as the screenwriter of The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971). For some in Ireland, this film is a dim but impressive memory, glimpsed on late-night television during its only broadcast in 1984. The Outcasts over the decades became a piece of Irish cinema legend, less seen and more peppered into conversations revolving around obscure celluloid. The Irish Film Institute describes this film as “folk horror”, a phrase I find too liberally applied these days to just about anything featuring sticks, rocks, and goats or set in the countryside. The Outcasts does not necessarily strive for the ultimate unified effect of horror. Instead, this film is of a rarer breed, more akin to Penda’s Fen (1974) in its otherworldly ruminations. I’ve come to prefer the phrase “folk revelation” as perhaps a more accommodating description for these sorts of stories. Whatever the case, I hope you get to see this remarkable film.

Brian J. Showers

Æon House, Dublin

25 September 2024

A brief side note, albeit a morbid one: Mangan penned an addendum noting that Edgeworth died during the composition of his sketch. Edgeworth died on 22 May 1849; the sketch was published on the 26th of the same month; Mangan himself scarcely survived another month, dying on 20 June 1849. Edgeworth was buried in the churchyard at St. John’s in Edgeworthstown; Mangan rests in Glasnevin Cemetery on the northside of Dublin.

A brief side note, albeit a morbid one: Mangan penned an addendum noting that Edgeworth died during the composition of his sketch. Edgeworth died on 22 May 1849; the sketch was published on the 26th of the same month; Mangan himself scarcely survived another month, dying on 20 June 1849. Edgeworth was buried in the churchyard at St. John’s in Edgeworthstown; Mangan rests in Glasnevin Cemetery on the northside of Dublin.

EDITOR’S NOTE

EDITOR’S NOTE

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

Notable Works

Notable Works

A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier

A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier