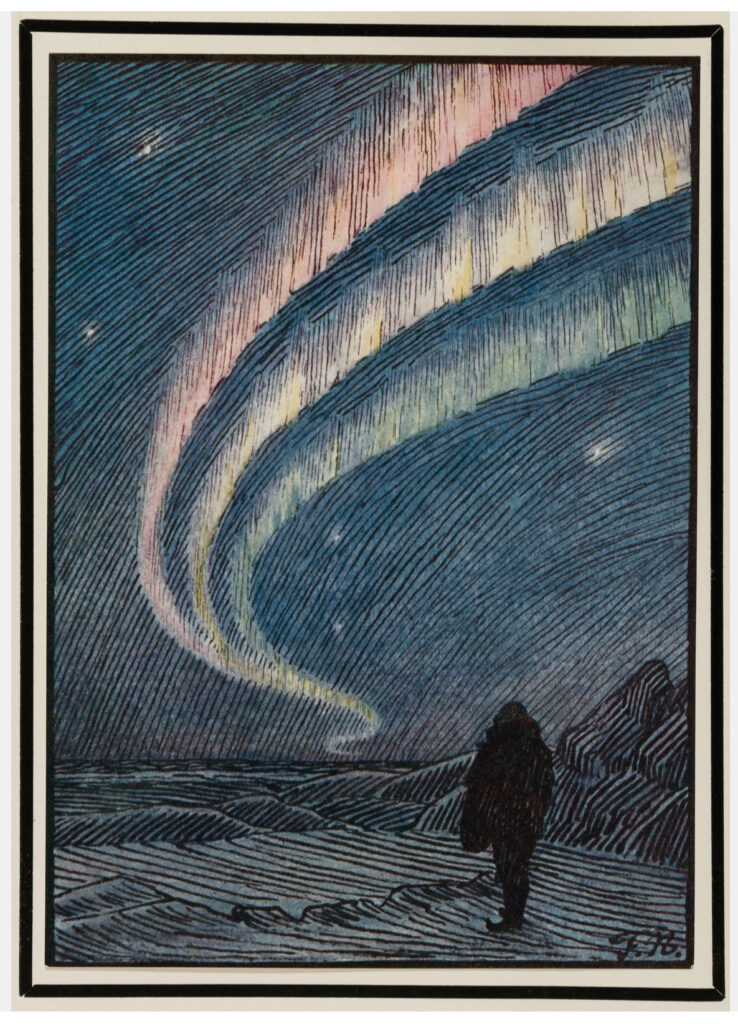

Fridtjof Nansen

After another cycle around the sun, and as the darker days of winter approach, it’s time to look back at what we managed to accomplish this year here at Swan River Press. Along the housing front, the sad answer is not too much. Æon House remains in something of a chaotic state as I continue renovating towards something resembling a grand vision. While most corners of Æon House are still somewhat confused, there are occasional glimpses of hospitable sanity. But enough of that. Onto Swan River . . .

The press was nominated this year for a British Fantasy Award in the “Best Independent Press” category. It’s always an honour to be nominated for an award, and I’ve noticed it’s happening more in recent years. We didn’t win this time around, but I did enjoy spending time in Brighton at the World Fantasy convention in Octobr, where we were sat in the trade hall beside our colleagues from Tartarus Press and Zagava. And our friend Steve J. Shaw, who takes care of Swan River’s typesetting duties, had better luck in Brighton, picking up a World Fantasy Award in the “Special Award—Non-Professional” category for his work with Black Shuck Books. Congratulations, Steve!

I also attended EasterCon in Belfast back in April. I’d not been to Belfast in ages, and had never attended an EasterCon, so this was a new adventure. As always, I couldn’t go to any panels, but I did get to spend a lot of time with both Helen Grant and Lynda E. Rucker, neither of whom I’d seen in a long time. Apparently Belfast will be hosting its own annual convention starting next year . . . should I go? Will you?

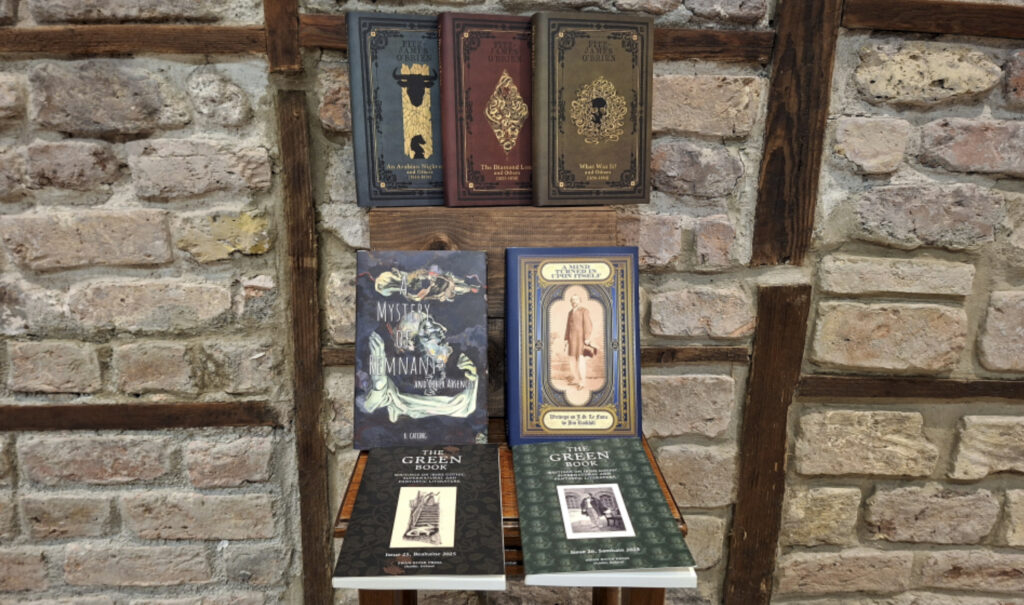

In November we participated in the Dublin Small Press Fair at the Pearse Street Library. We were surrounded by numerous publishers of every stripe and mode; a good reminder of the richness and vibrancy of Ireland’s publishing scene. The event, which included readings and panel discussions, was ably organised by Tom Groenland and Éireann Lorsung, with support from Dublin UNESCO City of Literature. It’s the sort of event that Dublin sorely needs, so kudos to the organisers. With luck, there will be another next year.

And now . . . onto the books!

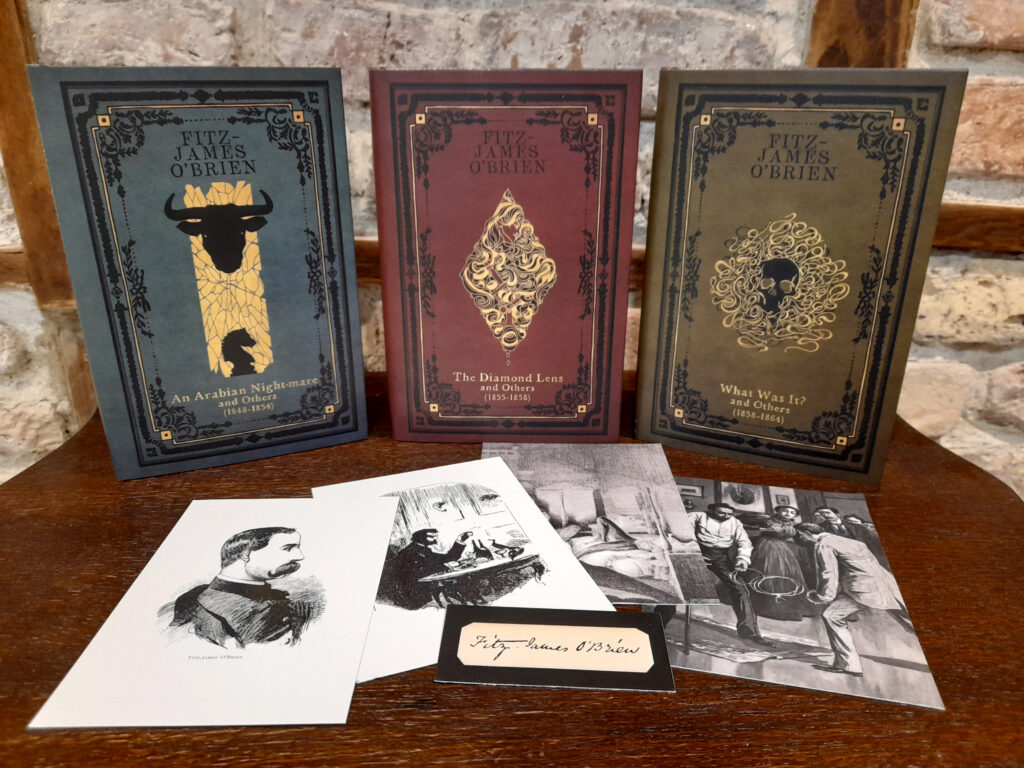

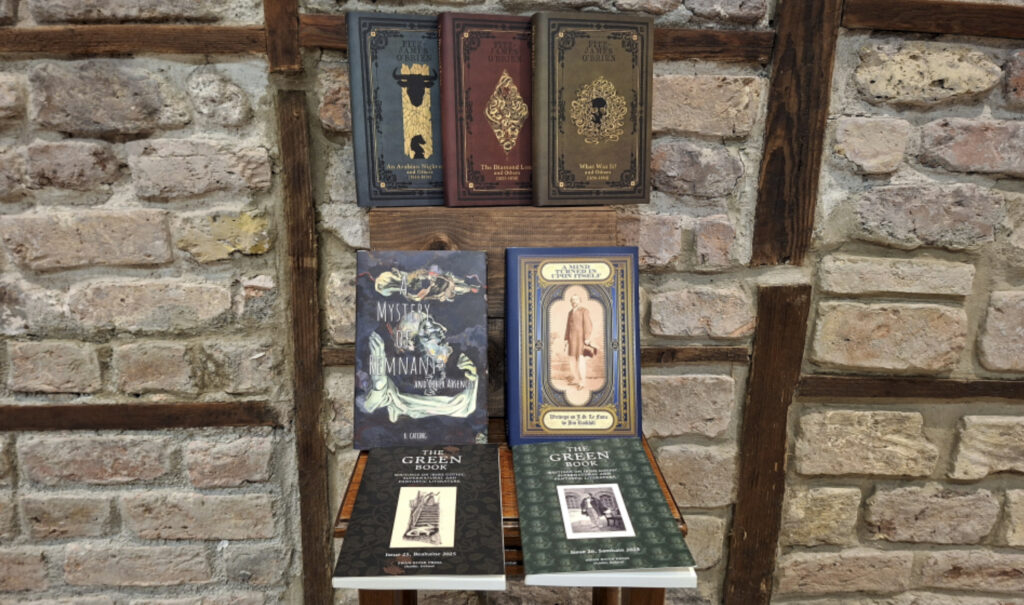

Our first publication this year was an ambitious three-volume Collected Speculative Works by the Cork-born writer Fitz-James O’Brien (1826/8-1862). O’Brien is notable for being at the forefront of genre when it was still in its infancy and the boundaries still blurred: he dabbled in satire, fantasy, horror, science fiction, ghost stories, and more. Pop Matters warmly reviewed the set as “the most comprehensive attempt yet to situate O’Brien firmly within the canon of 19th-century fantastical literature”, while Supernatural Tales wrote, “Quirky humour and darkly imaginative flourishes . . . [O’Brien is] a weaver of visionary images––a writer of reveries.”

Our first publication this year was an ambitious three-volume Collected Speculative Works by the Cork-born writer Fitz-James O’Brien (1826/8-1862). O’Brien is notable for being at the forefront of genre when it was still in its infancy and the boundaries still blurred: he dabbled in satire, fantasy, horror, science fiction, ghost stories, and more. Pop Matters warmly reviewed the set as “the most comprehensive attempt yet to situate O’Brien firmly within the canon of 19th-century fantastical literature”, while Supernatural Tales wrote, “Quirky humour and darkly imaginative flourishes . . . [O’Brien is] a weaver of visionary images––a writer of reveries.”

These three volumes––An Arabian Night-mare (1848-1854), The Diamond Lens (1855-1858), and What Was It? (1858-1864)––were a long time in the making. I’d estimate somewhere in the region of five years, if not longer. The project was originally proposed by editor John P. Irish, who assembled a career-spanning selection of O’Brien’s fantastical output, both prose and poetry. In an interview entitled “An Irish Wondersmith in New York”, John Irish positions O’Brien in both genre and broader literary contexts: “What continues to impress me about O’Brien is his foresight. His literary style was far ahead of its time. His short fiction incorporates modernist elements such as metafiction, unreliable narration, intertextuality, stream of consciousness, autofiction, and hyperreality—long before these techniques became hallmarks of the modernist movement.”

What makes this such an interesting project is the way in which you can track O’Brien’s development as a writer, one whose stories would become touchstones for later genre scribes. Each of the three volumes contains an introduction by Irish that guides us through O’Brien’s life, tragically cut short in the American Civil War; and so, in reading the set you get a full overview of O’Brien’s life and writing. If you want to know more, I wrote a short article “Publishing Fitz-James O’Brien”.

What makes this such an interesting project is the way in which you can track O’Brien’s development as a writer, one whose stories would become touchstones for later genre scribes. Each of the three volumes contains an introduction by Irish that guides us through O’Brien’s life, tragically cut short in the American Civil War; and so, in reading the set you get a full overview of O’Brien’s life and writing. If you want to know more, I wrote a short article “Publishing Fitz-James O’Brien”.

And here’s a nifty unboxing video from Too Many Books.

The cover art was provided by Brian Coldrick, who came up with a design to unify the three books. As always, I’m proud of the work we’ve produced; I believe this set now supersedes all previous volumes of O’Brien’s work. Thank you to everyone who took a chance on this one! Lovecraft observed that, “O’Brien’s early death undoubtedly deprived us of some masterful tales of strangeness and terror.” I think that’s probably true.

(Buy Collected Speculative Works here.)

Our next release this year was as much a collaborative memorial as it is a collection: A Mystery of Remnant and Other Absences by B. Catling. This is our second Catling book, the first being the novella Munky in 2020. After Catling passed away in September 2022, editors Victor Rees and Iain Sinclair set about assembling a volume of texts that would reflect Catling’s personal pantheon.

Our next release this year was as much a collaborative memorial as it is a collection: A Mystery of Remnant and Other Absences by B. Catling. This is our second Catling book, the first being the novella Munky in 2020. After Catling passed away in September 2022, editors Victor Rees and Iain Sinclair set about assembling a volume of texts that would reflect Catling’s personal pantheon.

The stories collected in A Mystery of Remnant are fragments of Catling’s singular imagination, portals into worlds populated by dog-headed giants and reanimated bog bodies, spirits both beastly and mundane. Tales about visionaries and mystics, about the need to venture into blurry territories of sight in which angels, ghosts and memories merge and reform. Together they showcase the distinctive voice underlying the very best of Catling’s work.

The collaborative aspect of this book is perhaps as important as the book itself: Victor Rees, who introduces the volume, is working on a PhD about Catling’s literature and performance art; Iain Sinclair, who provided photographs and an afterword, and Alan Moore, who supplied short prose pieces to accompany those photos, were long-time friends of Catling; while Eleanor Crook, who created the jacket art for the book, was one of Catling’s former students; and finally artist Jack Catling, who penned the foreword, is Brian’s son. Through them, Catling’s imagination continues to seep, saturate, and inspire.

The collaborative aspect of this book is perhaps as important as the book itself: Victor Rees, who introduces the volume, is working on a PhD about Catling’s literature and performance art; Iain Sinclair, who provided photographs and an afterword, and Alan Moore, who supplied short prose pieces to accompany those photos, were long-time friends of Catling; while Eleanor Crook, who created the jacket art for the book, was one of Catling’s former students; and finally artist Jack Catling, who penned the foreword, is Brian’s son. Through them, Catling’s imagination continues to seep, saturate, and inspire.

The reviews for this collection are both receptive and perceptive. The Ancillary Review called A Mystery of Remnant “a delightfully strange formal oddity of a book”, while You’re Reading observed, “This book is a composite picture of a complex and genuine iconoclast, an artist absorbed in an investigation of existence and non-existence, and the border between.” That all sounds about right to me.

“Catling never liked talking about process,” says Rees in a recent talk, “Exploring the Hollows”, “[instead] referring to his books as having written themselves, as though a kind of channelling had taken place in which he was simply there to mediate words that flowed through him into his laptop. Catling suggests the possibility that these words and voices may have reached him from someplace else.” And the stories in A Mystery of Remnant serve as glimpses to that “someplace else”.

A Mystery of Remnant was one of our fastest sellers this year; as I write this, only a handful of hardback copies remain. I’m not sure yet if there will be a paperback edition, so if you’re interested, you’d best pick up a copy now.

(Buy A Mystery of Remnant here.)

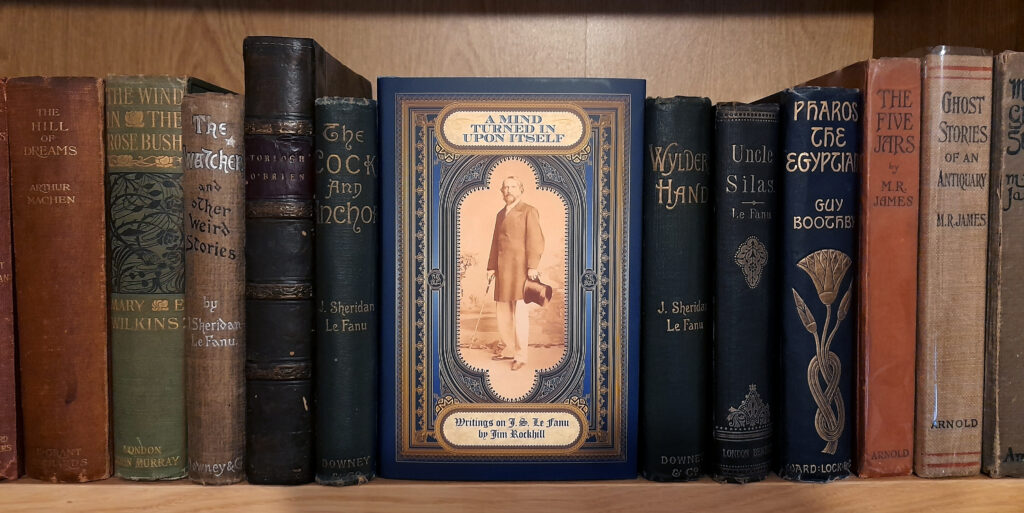

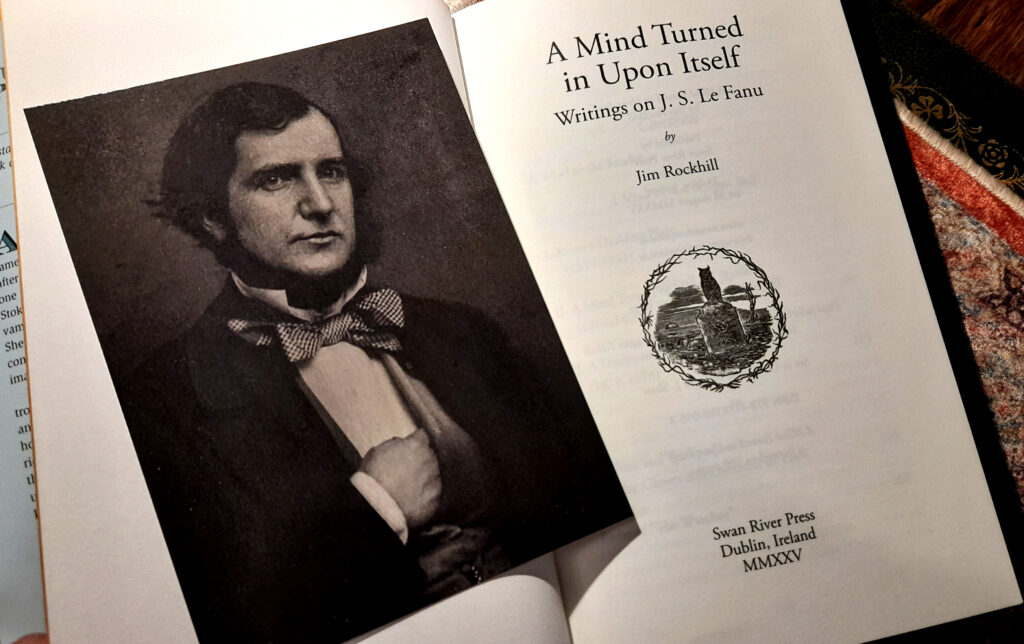

And finally, we have Jim Rockhill’s A Mind Turned in Upon Itself: Writings on J. S. Le Fanu. This is another project long in the making. The core of this volume consists of the introductions Jim wrote for Ash Tree Press’s definitive, but out of print, three-volume ghost stories of Le Fanu. Now collected, revised, and expanded, A Mind Turned in Upon Itself is an excellent overview of Le Fanu’s life and supernatural literature. This non-fiction collection—our first?—is rounded out by a handful of Jim’s other essays on Le Fanu, making this a real treasure trove.

And finally, we have Jim Rockhill’s A Mind Turned in Upon Itself: Writings on J. S. Le Fanu. This is another project long in the making. The core of this volume consists of the introductions Jim wrote for Ash Tree Press’s definitive, but out of print, three-volume ghost stories of Le Fanu. Now collected, revised, and expanded, A Mind Turned in Upon Itself is an excellent overview of Le Fanu’s life and supernatural literature. This non-fiction collection—our first?—is rounded out by a handful of Jim’s other essays on Le Fanu, making this a real treasure trove.

Jim is an ardent admirer of Le Fanu’s work, and in “Dreaming of Shadow and Smoke”, he explains how that came about: “I first encountered Le Fanu through Wise and Fraser’s Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural. Having reached the innocuously-titled “Green Tea” on a pleasant afternoon while visiting my grandparents, I was shocked at the world the story depicted. [It] terrified me on a more fundamental level than anything else I had read in the book.”

You’re Reading gave the book an incredibly kind notice: “In A Mind Turned in Upon Itself, Jim Rockhill abundantly demonstrates his love and appreciation for J. S. Le Fanu’s fiction and presents such an enthusiastic examination of the work as to inspire people to seek out whatever of that work they have not so far read. Highly recommended.”

You’re Reading gave the book an incredibly kind notice: “In A Mind Turned in Upon Itself, Jim Rockhill abundantly demonstrates his love and appreciation for J. S. Le Fanu’s fiction and presents such an enthusiastic examination of the work as to inspire people to seek out whatever of that work they have not so far read. Highly recommended.”

John Coulthart did a great cover for us too, and the eagle-eyed will notice Le Fanu’s monogram embedded in the design. As a bonus, back in September, Jim visited Æon House here in Dublin shortly after the book was published and kindly signed the entire print run. A Mind Turned in Upon Itself is the perfect accompaniment to long-time fans of Le Fanu and those who are exploring his ghostly oeuvre for the first time.

(Buy A Mind Turned in Upon Itself here.)

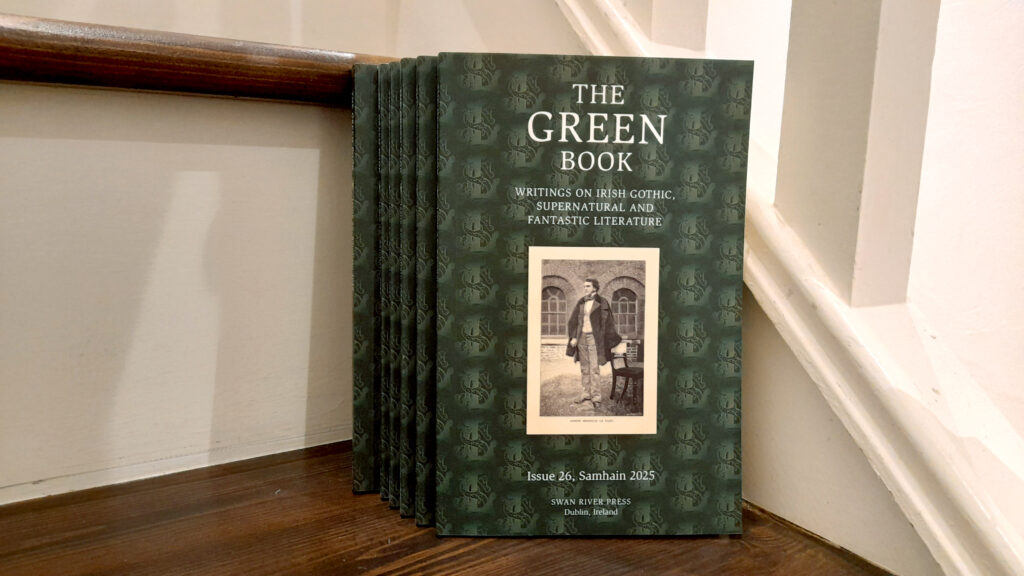

Which brings us to this year’s issues of The Green Book: Writing on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Fiction. And as luck may have it, both issues this year are devoted to Le Fanu.

Which brings us to this year’s issues of The Green Book: Writing on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Fiction. And as luck may have it, both issues this year are devoted to Le Fanu.

Issue 25 boasts several rare Le Fanu items, including a memoir by Le Fanu’s friend and publisher Edmund Downey that had not been reprinted in over one hundred years. We’ve expanded Le Fanu’s bibliography, if only in a minor way, by making a new poetry attribution. You’ll also find rare reprint of Le Fanu’s “Some Gossip About Chapelizod”, as well as commentaries on these aforementioned texts. Finally, there’s the bizarre story of a sequel to “Green Tea” published in 1942 by the German writer O. C. Recht. If you want to know more, check out the Editor’s Note.

Issue 26 was another Le Fanu issue. We reprinted “My Aunt Margaret’s Adventure”, which was first attributed to Le Fanu by M. R. James, but passed over for inclusion in Madam Crowl’s Ghost (1923). There are two contributions from Le Fanu’s siblings, including extracts from William Le Fanu’s Seventy Years of Irish Life, plus the sole short story written by his sister Catherine, reprinted here for the first time. Lastly, you’ll find two pieces concerning Le Fanu passing: the first being a collection of obituaries, and the second an attempt at deciphering the capstone of Le Fanu’s vault. An absolute wealth for Le Fanu aficionados. Again, read the Editor’s Note if you’re curious.

was another Le Fanu issue. We reprinted “My Aunt Margaret’s Adventure”, which was first attributed to Le Fanu by M. R. James, but passed over for inclusion in Madam Crowl’s Ghost (1923). There are two contributions from Le Fanu’s siblings, including extracts from William Le Fanu’s Seventy Years of Irish Life, plus the sole short story written by his sister Catherine, reprinted here for the first time. Lastly, you’ll find two pieces concerning Le Fanu passing: the first being a collection of obituaries, and the second an attempt at deciphering the capstone of Le Fanu’s vault. An absolute wealth for Le Fanu aficionados. Again, read the Editor’s Note if you’re curious.

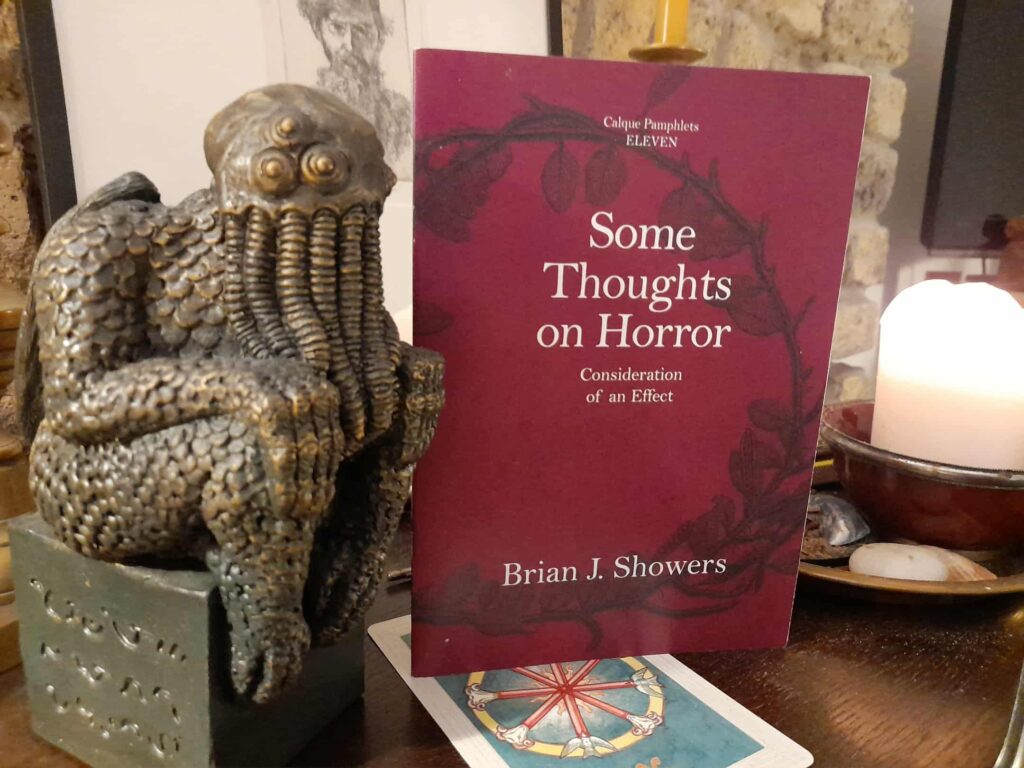

Although not a Swan River Press publication, I’d like to draw your attention to a short monograph I wrote for our friends at Calque Press entitled Some Thoughts on Horror: Consideration of an Effect. It’s a three-part essay, the first part of which some of you will recognise as my musings from the introduction to the now out of print Uncertainties 5. It turned out I had more to say on the subject of how we approach and appreciate horror, so if you like reading that sort of thing, do pick up a copy of this limited edition pamphlet.

Although not a Swan River Press publication, I’d like to draw your attention to a short monograph I wrote for our friends at Calque Press entitled Some Thoughts on Horror: Consideration of an Effect. It’s a three-part essay, the first part of which some of you will recognise as my musings from the introduction to the now out of print Uncertainties 5. It turned out I had more to say on the subject of how we approach and appreciate horror, so if you like reading that sort of thing, do pick up a copy of this limited edition pamphlet.

(Buy Some Thoughts on Horror here.)

For those interested in statistics, we published 7 new titles this year, totalling 1,480 pages; 2,250 copies; and 392,613 words. That includes this year’s issues of The Green Book.

If you’re looking to keep tabs on what we get up to throughout the year, the best way is probably to sign up for our newsletter. Apart from that, we can be found on Instagram, Facebook, Bluesky, and Threads. So if you don’t want to miss out on any announcements or exciting books, do give us a follow.

And just to draw everyone’s attention to it, you can use the filters on our Titles page to see which books are on the Low Stock Report—the ones that might not be around much longer. The filter menus are a handy tool, I use them quite a bit myself. There are a few titles now in short supply, which you’re better off picking up now while they’re still at cover price.

And just to draw everyone’s attention to it, you can use the filters on our Titles page to see which books are on the Low Stock Report—the ones that might not be around much longer. The filter menus are a handy tool, I use them quite a bit myself. There are a few titles now in short supply, which you’re better off picking up now while they’re still at cover price.

Of course, as always, I am grateful to the Swan River Press team: Meggan Kehrli, Jim Rockhill, Steve J. Shaw, Timothy J. Jarvis, and John Kenny. I don’t think I could have assembled a more dedicated and talented group, each of whom helps to keep Swan River Press running smoothly and at the calibre you’ve come to expect.

If you’ve read this far, you might be curious what we’ve got in store for next year. Well, there will be another two issues of The Green Book, I know that much. And we’ve a full roster of hardbacks for 2026. In fact, I’ve probably more titles than I’ll be able to publish, which I guess means we’re also lining up for 2027. While I don’t like to announce titles in advance, I will say that I’ve got two lined up for early in the new year, which I hope you’ll like.

Thank you again to everyone who has bought and read our books this year, or otherwise shown us support and encouragement. I particularly enjoyed getting to conventions and fairs to meet people, so with luck there will be more of that over the coming twelve months. Until then, please stay healthy, take care of each other, support your public services, vote, and be sure to keep your communities fascist free.

And may your festive season be filled with shadows, wonderment, and joy!

Brian J. Showers

Æon House, Dublin

2 December 2025

Conducted by Brian J. Showers

Conducted by Brian J. Showers Alison Moore (“Where Are They Now?”)

Alison Moore (“Where Are They Now?”) Méabh de Brún (“Consumed as in Obsessed”)

Méabh de Brún (“Consumed as in Obsessed”)

Living for four years in Dublin was the best possible preparation for appreciating that London could never be excavated in that way. London was not a project for me. It was the curse that never stops giving. A Faustian contract to be worked out through fortunate collaborations, in poetry, film, performance, pilgrimage. Pulling away from London gravity was never successful. Those books were barely noticed or permitted. The point was to live there, to begin with the first step outside my Hackney door. To dig in, to stay. To honour characters who presented themselves and demanded a cameo.

Living for four years in Dublin was the best possible preparation for appreciating that London could never be excavated in that way. London was not a project for me. It was the curse that never stops giving. A Faustian contract to be worked out through fortunate collaborations, in poetry, film, performance, pilgrimage. Pulling away from London gravity was never successful. Those books were barely noticed or permitted. The point was to live there, to begin with the first step outside my Hackney door. To dig in, to stay. To honour characters who presented themselves and demanded a cameo.

I should say that the stories were put together in a posthumous dialogue with Brian Catling. And as a companion piece to

I should say that the stories were put together in a posthumous dialogue with Brian Catling. And as a companion piece to  While the literary/film characters of the book fill the pages, it is the peppering in of people like William Lyttle that add an extra dimension to your writing. (Less of a question and more calling out an aspect I loved. On second reading, I sat with Google by my side and fell down many enjoyable/educational rabbit holes, was that your intention?) That kind of interplay between a text and the digital world didn’t exist twenty years ago—what, if any, impact do you think that has had on your writing?

While the literary/film characters of the book fill the pages, it is the peppering in of people like William Lyttle that add an extra dimension to your writing. (Less of a question and more calling out an aspect I loved. On second reading, I sat with Google by my side and fell down many enjoyable/educational rabbit holes, was that your intention?) That kind of interplay between a text and the digital world didn’t exist twenty years ago—what, if any, impact do you think that has had on your writing? Sinclair: I don’t know how “natural” the process is. But there is no pecking order: maps are usually involved, but I might not consult them until the walks are done. And those maps tend to be so old that they have the charm of fiction. Key buildings and sites have vanished. The latest interventions are not yet admitted. The Secret State redacts inconvenient military installations, pharmaceutical and “experimental” facilities. London documentation has to ooze through the cracks in forbidden zones. There is a perpetual struggle to outperform CGI boasts and projections. Writing is a dangerous negotiation. You pay a price to be admitted to the game.

Sinclair: I don’t know how “natural” the process is. But there is no pecking order: maps are usually involved, but I might not consult them until the walks are done. And those maps tend to be so old that they have the charm of fiction. Key buildings and sites have vanished. The latest interventions are not yet admitted. The Secret State redacts inconvenient military installations, pharmaceutical and “experimental” facilities. London documentation has to ooze through the cracks in forbidden zones. There is a perpetual struggle to outperform CGI boasts and projections. Writing is a dangerous negotiation. You pay a price to be admitted to the game.