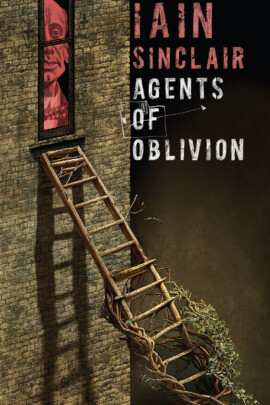

Agents of Oblivion

Iain Sinclair

Availability: In Print – Paperback, Out of Print – Hardback

“How long have things been coming apart in this way?” – The Lure of Silence

“Generally speaking the dead do not return,” pronounced Antonin Artaud. But the dead are permitted to visit those who welcome them. Their spectral, machine-made voices echo in deep tunnels under London. Voices without hosts. Without agency. They make their oracular pronouncements even when nobody is listening on the vast empty platforms of the Elizabeth Line. They have their codes and their secret meanings.

Four stories starting everywhere and finishing in madness. Four acknowledged guides. Four tricksters. Four inspirations. Algernon Blackwood. Arthur Machen. J. G. Ballard. H. P. Lovecraft. They are known as “Agents of Oblivion”. And sometimes, in brighter light, as oblivious angels . . .

As host, as oracle, Iain Sinclair moves through this quartet of tales, through a spectral London that once was, or might never have been.

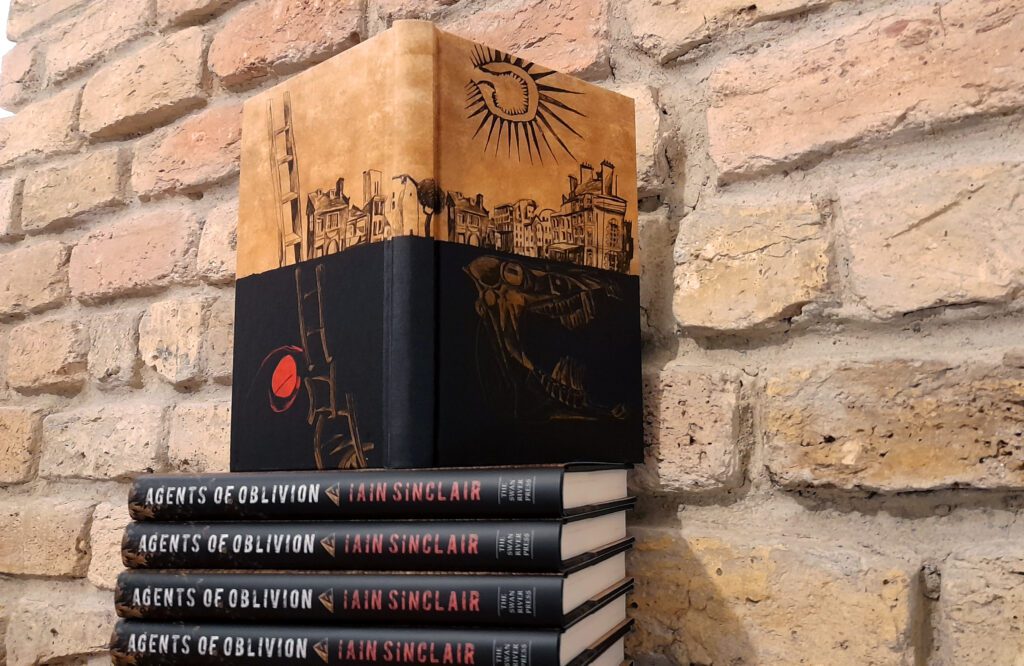

Our limited edition hardback is sold out.

Please check with our Booksellers for remaining copies.

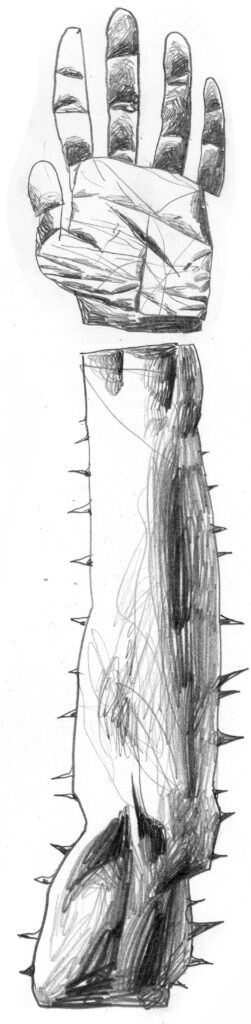

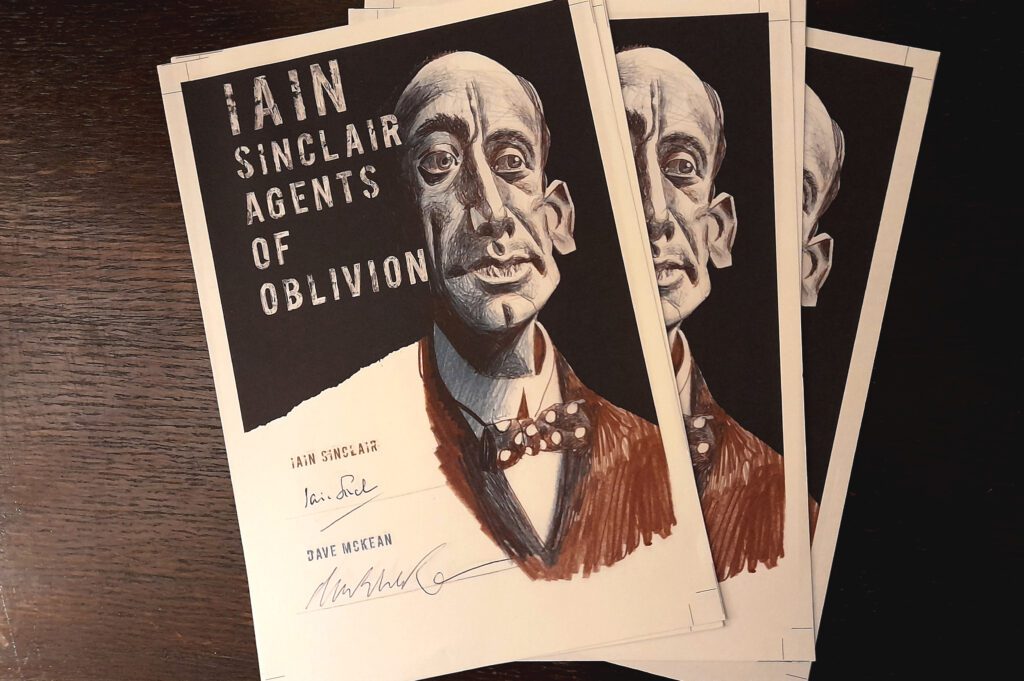

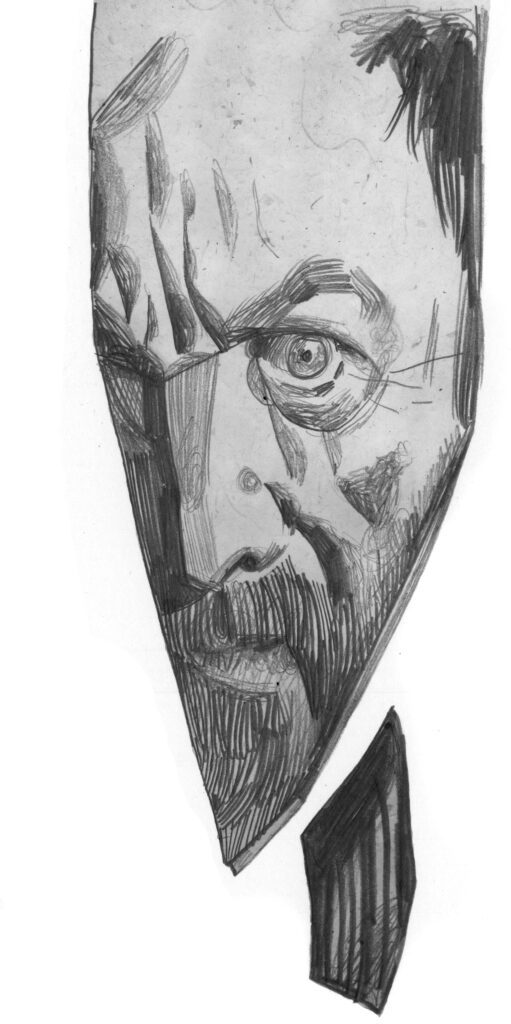

Cover art and illustrations by Dave McKean

ISBN: 978-1-78380-044-5 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-78380-771-0 (pbk)

Contents

“Code 4: Agents of Oblivion”

“The Lure of Silence”

“House of Flies”

“London Spirit”

“At the Mountains of Madness”

“Acknowledgements”

“About the Author”

“About the Illustrator”

“Code 4: Agents of Oblivion”

“Code 4: Agents of Oblivion”

“Generally speaking the dead do not return,” Artaud pronounced in a prose poem called “Electroshock”, composed after his involuntary transit from Dublin to the tender care of French asylums. Lunatic. Straitjacket. No return to any of his earlier selves. Artaud was a seeker but there was nothing economic about his migration. The dead are permitted to visit those who welcome them. Their spectral, machine-made voices echo in deep tunnels under London. Voices without hosts. Without agency. They make their oracular pronouncements even when nobody is listening on the vast empty platforms of the Elizabeth Line. They have their codes and their secret meanings.

Code 4 alerts transport operatives to an unspecified violation: “spillage”. It is not blood or shit or vomit, this time. Narrative spillage. Ghost stories leaking through a permeable membrane between remembered experience and high fiction, between the living dead and the unquiet residents of other dimensions. Sleepwalking voyagers are on the drift, tapped by angels, prodded by demons. They are known as “Agents of Oblivion”. They do not possess badges or guns. And they did not take their inspiration from a defunct swamp rock combo of the last millennium. But there are no coincidences in the city of shadows. Four stories starting everywhere and finishing in madness. Four acknowledged guides. Four tricksters. Four inspirations. Blackwood. Machen. Ballard. Lovecraft. Spillage on the line. God’s face is pressing against a suburban window. We are becalmed in crisis. Phones twitter like starlings. Books are burning.

Iain Sinclair

Iain Sinclair has lived in Hackney since 1968, working at a variously titled London project. He has published widely through mainstream and independent presses. These crimes have been comprehensively collected in a three-volume bibliography/biography by Jeff Johnson. Now published by Test Centre Books. An early prose-poetry trilogy was followed by the novels Downriver and Radon Daughters. The short-story collection, Slow Chocolate Autopsy, was a first collaboration with Dave McKean. Sinclair was formerly a used-book dealer and never quite got over it.

Read more“Classic Sinclair . . . a hugely entertaining addition to his canon.” (starred review) – Fortean Times

“Nobody can do more with a sentence’s cadence, diction and imagery than Sinclair.” – Washington Post

“In his unique, sinewed style. For no-one can write / Like Iain Sinclair on this planet, and indeed, / While reading one detects an empirically alien view” – International Times

“Four original stories, perfectly illustrated by Dave McKean.” – Ellen Datlow

“[Sinclair’s] writing is inspiring, teasing and often revelatory. He explores themes I enjoy: London as Blake saw it, the New Jerusalem shining through in the city’s occult geometry, its history both mundane but primarily of mysticism, of the weird, as told by its writers past and present, of Swedenborg, Machen, Ballard, Blackwood.” – Flapjacks and Coffee

“In Agents of Oblivion Iain Sinclair offers four stories riffing off writers who have always worked, like himself, on the borderlands of our consciousness. Unfamiliar with two of these—Lovecraft and Blackwood—I was persuaded, through Sinclair’s oracular references, to try them again. His interpretations of Ballard and Machen are as illuminating as we might expect from a highly original author whose extraordinary prose offers biography, reminiscence, autobiography, and his own idiosyncratic insights. He blends urban mythology with criticism, and fiction with memoir, re-introducing a now-familiar pantheon which includes writer/shaman Alan Moore, the late multi-talented Brian Catling (Vorrh) and legendary bookselling rock guitarist Martin Stone, all of whom, under their own names as well as earlier pseudonyms, have graced Sinclair’s personal mythology since White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings and Radon Daughter first appeared. With his lensman’s eye and his poet’s gift for glowing, precise language, Sinclair illuminates and sometimes terrifies the soul! Augmented by a profusion of images by his old partner Dave McKean, Agents of Oblivion is probably one of the best collections of fiction I have read. I expect it to bear many fresh insights in years to come.” – Michael Moorcock

Agents of Oblivion by Iain Sinclair; cover art and interior illustrations by Dave McKean; jacket production by Meggan Kehrli; edited by Brian J. Showers and Timothy J. Jarvis; copyedited by Jim Rockhill; typeset by Steve J. Shaw; published by Swan River Press at Æon House.

Hardback: Published on 3 May 2023; limited to 550 copies of which 100 were embossed and hand numbered; signed by Iain Sinclair and Dave McKean; 191 pages; lithographically printed on 90 gsm paper; dust jacketed; illustrated Wibalin boards; sewn binding; head- and tail-bands; ISBN: 978-1-78380-044-5.

Paperback: Published on 31 August 2023; no limitation; print on demand paperback; 191 pages; ISBN: 978-1-78380-771-0.

“About the Illustrator”

“About the Illustrator”

Dave McKean has illustrated and designed many ground breaking books and graphic novels including The Magic of Reality (Richard Dawkins), The Homecoming (Ray Bradbury), The Savage (David Almond), What’s Welsh for Zen (John Cale), Arkham Asylum (Grant Morrison) and Mr. Punch, Wolves in the Walls, Coraline, and The Graveyard Book (Neil Gaiman). He wrote and illustrated Pictures That Tick, Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash, and the multi-award winning Cages. He has created hundreds of CD and comic covers including the entire run of Gaiman’s Sandman. He has directed five short and three feature films, MirrorMask, Luna, and The Gospel of Us with Michael Sheen.

“Excavating Oblivion”:

“Excavating Oblivion”:

In Conversation with Iain Sinclair

Conducted by Matthew Stocker, June 2023

Matthew Stocker: I honestly didn’t know how to open this interview, then yesterday I was in a restaurant with my children and wife and I spotted beside many bits of Joyce paraphernalia a quote;

“I want to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book.”

In Agents of Oblivion, Dublin is mentioned once or twice in passing, but with regards London do you see yourself undertaking the same type of project as Joyce attempted for Dublin?

Iain Sinclair: Dublin wrote Joyce into existence. The city identified its ideal scribe at the optimum moment when the solid structures and achievements of nineteenth-century fiction were ready to be absorbed into the permissions of high modernism. Those special theories of everything hovering over the sweat and stink and chatter. Joyce, as the chosen instrument, had to be expelled, forced to carry out his epic sequence of masterworks at a safe distance. Whatever the cost. Whatever the collateral rewards. Poverty, vanity, a Swiss grave. He gave everything to become—the horror of it!—a cultural resource. A brand. Municipal real estate pimped for cultural tourism. But he links very neatly with the Protestant austerity of Beckett. The one who could revise and refine the task, strip it down, and carry it away from the choking rituals, the provincialism, and the heady particulars of a mesmerising and Oedipal port city.

Living for four years in Dublin was the best possible preparation for appreciating that London could never be excavated in that way. London was not a project for me. It was the curse that never stops giving. A Faustian contract to be worked out through fortunate collaborations, in poetry, film, performance, pilgrimage. Pulling away from London gravity was never successful. Those books were barely noticed or permitted. The point was to live there, to begin with the first step outside my Hackney door. To dig in, to stay. To honour characters who presented themselves and demanded a cameo.

Living for four years in Dublin was the best possible preparation for appreciating that London could never be excavated in that way. London was not a project for me. It was the curse that never stops giving. A Faustian contract to be worked out through fortunate collaborations, in poetry, film, performance, pilgrimage. Pulling away from London gravity was never successful. Those books were barely noticed or permitted. The point was to live there, to begin with the first step outside my Hackney door. To dig in, to stay. To honour characters who presented themselves and demanded a cameo.

Stocker: The book, Agents of Oblivion, is dedicated to B. Catling and he appears within the text alongside a plethora of other literary giants. I was saddened to read of his passing, I really enjoyed The Vorrh trilogy and Munky (published by Swan River Press, also illustrated by McKean); it makes a lovely companion with Agents.

Why Blackwood, Machen, Ballard, and Lovecraft? Writers/characters such as Brian and Alan Moore and Steve Moore (no relation) play almost a bigger role as travellers through the textuality.

Sinclair: Again, it felt as if those writers, with their own haunting characteristics—writers much more implicated in generic tropes than Joyce—were authentic witnesses and contributors to the weave of London mythology. Reading them, they nudge the pen. They whisper.

They have laid out the model. But it is not finished, never finished. Their words remain contemporary. They are our psychic landscape as much as Woolwich or Farringdon Road or Northolt.

The characters from our own times, like Alan Moore, Brian Catling, and Steve Moore, have doubled identities. They shape worlds, they mine extraordinary language reserves—and they also share experiences that I can subvert or celebrate. As ever: “The living can assist the imaginations of the dead.” And vice versa. Those writers know how to take the dictation and how to exploit it. They pass on the obligations of attentive readership. They pilot the future.

Stocker: Does the book serve a double purpose, on one side to be read/enjoyed/absorbed in its own right, but also as a reading list for the initiate to dive into? As a syllabus, I have been racking my mind as to what the course would be called.

Sinclair: It is my reading list at the time of writing these stories, a period of a few months. It is not a pitch for an established academic discipline. Nobody is required to locate and absorb every referenced figure. I haven’t read those books at an examination pitch. I dipped and pecked and reached out for the shelves when things were flagging.

I should say that the stories were put together in a posthumous dialogue with Brian Catling. And as a companion piece to Munky, the novella he published with Swan River. That also came with perfectly sympathetic drawings by Dave McKean. It was Catling who pointed me towards Blackwood and the John Silence stories the first time I visited his family home, off the Old Kent Road. He was also, in the late 1960s, a devourer of Lovecraft. I heard many stories of Ballard and the era of New Worlds from Mike Moorcock. I appreciated that lineage, what passed down from Moorcock, Ballard, Angela Carter to Alan Moore and Catling. They tapped the fabric of London as London prodded them.

I should say that the stories were put together in a posthumous dialogue with Brian Catling. And as a companion piece to Munky, the novella he published with Swan River. That also came with perfectly sympathetic drawings by Dave McKean. It was Catling who pointed me towards Blackwood and the John Silence stories the first time I visited his family home, off the Old Kent Road. He was also, in the late 1960s, a devourer of Lovecraft. I heard many stories of Ballard and the era of New Worlds from Mike Moorcock. I appreciated that lineage, what passed down from Moorcock, Ballard, Angela Carter to Alan Moore and Catling. They tapped the fabric of London as London prodded them.

Brian was responding, to his last breath. He projected a fourth volume of The Vorrh, in parallel with Surreycide, a questing return to the mythology of a rubbled childhood among the tenements and canals of Camberwell. That city, that time. The museums lying in wait as he rode in a London bus alongside his adopted father. Because it was always the boy who chose his parent. Who recognised and teased the inheritance from William Blake.

Stocker: You appear to take the reader on a journey linking author after author and their works, it goes beyond intertextuality. It feels like a ghost story, the writers you write about haunt the places and live on in both their writing and the landscape (I should note not all the characters are dead—Alan Moore for one).

While the literary/film characters of the book fill the pages, it is the peppering in of people like William Lyttle that add an extra dimension to your writing. (Less of a question and more calling out an aspect I loved. On second reading, I sat with Google by my side and fell down many enjoyable/educational rabbit holes, was that your intention?) That kind of interplay between a text and the digital world didn’t exist twenty years ago—what, if any, impact do you think that has had on your writing?

While the literary/film characters of the book fill the pages, it is the peppering in of people like William Lyttle that add an extra dimension to your writing. (Less of a question and more calling out an aspect I loved. On second reading, I sat with Google by my side and fell down many enjoyable/educational rabbit holes, was that your intention?) That kind of interplay between a text and the digital world didn’t exist twenty years ago—what, if any, impact do you think that has had on your writing?

Sinclair: Not much. Beyond the convenience of checking dates and facts, with frequently unreliable results. Sometimes—as with the walking films of John Rogers on YouTube—I find inspiration, confirmation. In general, the digital world is a swamp. Easier to drown than swim.

Stocker: As you write, do you start with a map to the journey you take the reader on both with regards the physical places you bring them and the writers that inhabit them? Or is it a chain of events, one naturally leading to the other as you wrote?

Sinclair: I don’t know how “natural” the process is. But there is no pecking order: maps are usually involved, but I might not consult them until the walks are done. And those maps tend to be so old that they have the charm of fiction. Key buildings and sites have vanished. The latest interventions are not yet admitted. The Secret State redacts inconvenient military installations, pharmaceutical and “experimental” facilities. London documentation has to ooze through the cracks in forbidden zones. There is a perpetual struggle to outperform CGI boasts and projections. Writing is a dangerous negotiation. You pay a price to be admitted to the game.

Sinclair: I don’t know how “natural” the process is. But there is no pecking order: maps are usually involved, but I might not consult them until the walks are done. And those maps tend to be so old that they have the charm of fiction. Key buildings and sites have vanished. The latest interventions are not yet admitted. The Secret State redacts inconvenient military installations, pharmaceutical and “experimental” facilities. London documentation has to ooze through the cracks in forbidden zones. There is a perpetual struggle to outperform CGI boasts and projections. Writing is a dangerous negotiation. You pay a price to be admitted to the game.

Stocker: The artwork in the book is phenomenal, I am an avid fan of Dave McKean. (Loved your previous collaboration, Slow Chocolate Autopsy) How does that process work, how does the end product gel with the imagery in your head as you write?

Sinclair: Dave has a preternatural gift for fine-tuning his imagery to the extravagant conceits of my prose. In practical terms, as I discovered from the start, with Slow Chocolate Autopsy and London Orbital, the best way forward was to send Dave a bunch of my research snapshots—places, characters, and incidents from which the fiction took off. Dave has that classic Victorian or Edwardian gift of catching the lineaments of character and exaggerating them to achieve a higher truth.

He would do what you wanted, what you pre-imagine—and then much more. I did not for a moment conceive of the range of illustrations he would extract from Agents of Oblivion. What he delivered made it a different and richer book, a graphic novella.

Dave’s animated interventions boosted the films I made for Channel 4 with Chris Petit. There was an unforgettable moment in The Falconer when he finessed a vampiric Hammer Films seizure out of an overheated television interview Peter Whitehead conducted with a Norwegian woman, when he talked about cohabiting with raptors.

Matthew Stocker, a graduate of the English Department of Trinity College Dublin and occasional storyteller, lives under the kitchen table and tells stories for food.