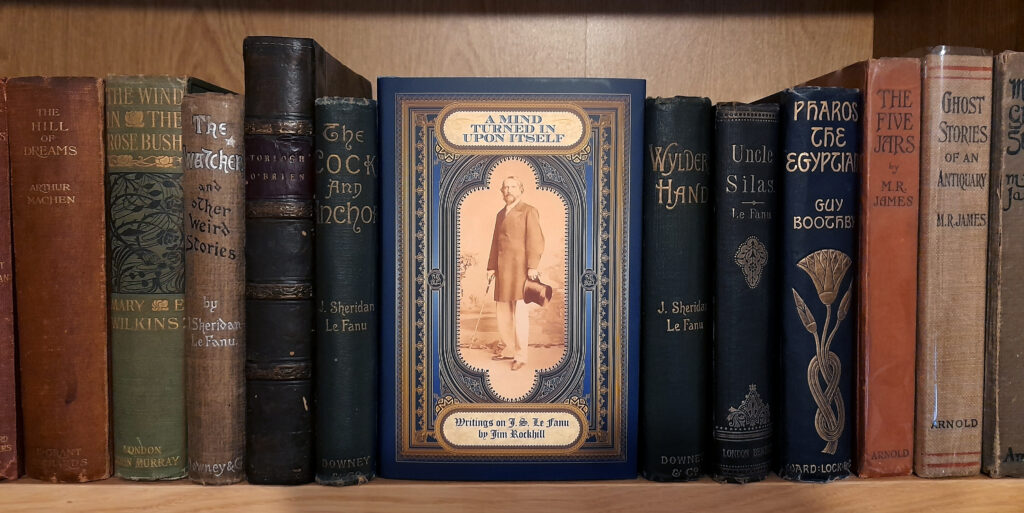

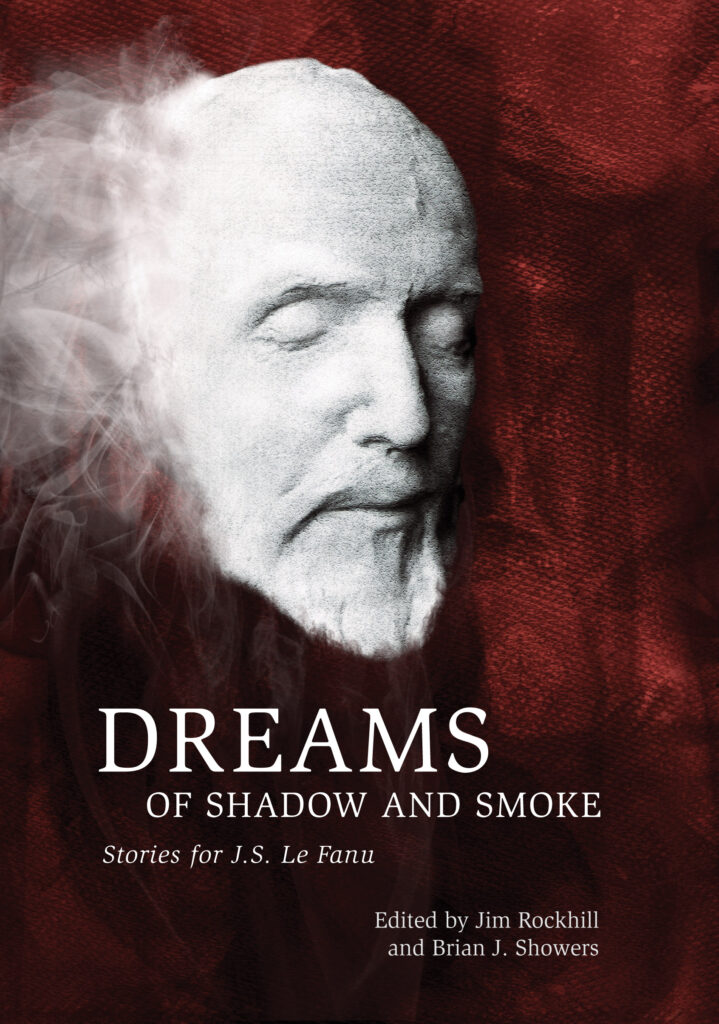

A Mind Turned in Upon Itself

Writings on J. S. Le Fanu

Jim Rockhill

Availability: In Print – Hardback

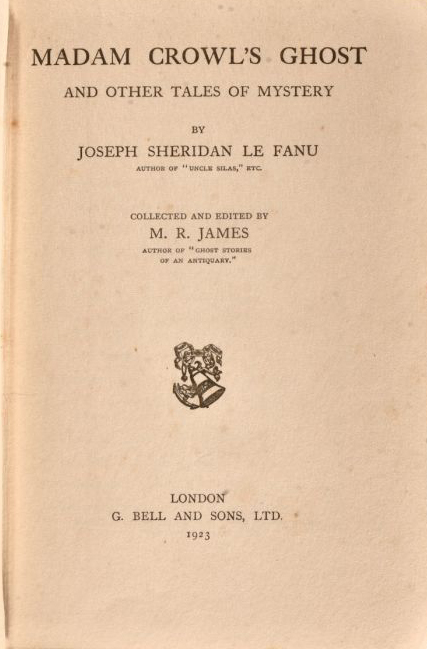

“He stands absolutely in the first rank as a writer of ghost stories.” – M. R. James

A major influence on M. R. James, considered by Henry James “ideal reading for the hours after midnight”, and thought to be one of the inspirations for Bram Stoker’s Dracula through his classic vampire tale “Carmilla”—Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s ghost stories continue to loom large in the Gothic imagination.

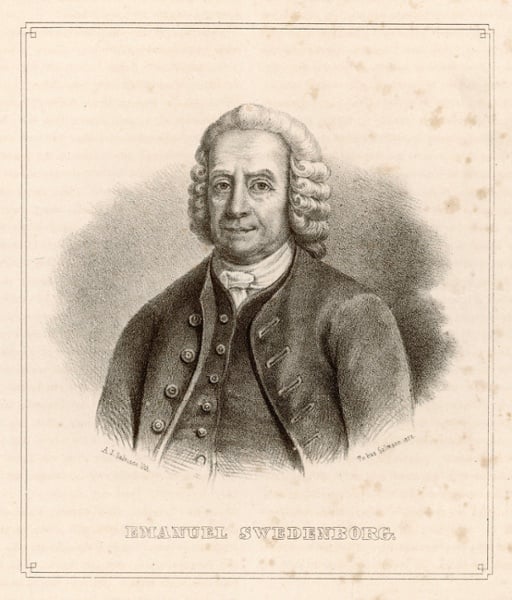

This study considers Le Fanu’s troubled life, his haunting stories, and his continued influence on horror literature by exploring the richness of his imagination, and the finesse with which he expands upon and combines elements of Irish folklore, the mysticism of Swedenborg, and the nascent science of psychology. In this volume, Jim Rockhill goes beyond such classics as “Green Tea” and “Schalken the Painter” by examining the manifold avenues of terror offered throughout the work of Ireland’s master of supernatural terror.

- More on Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu can be found in various issues of The Green Book

Hardback edition limited to 350 copies.

Signed by the author.

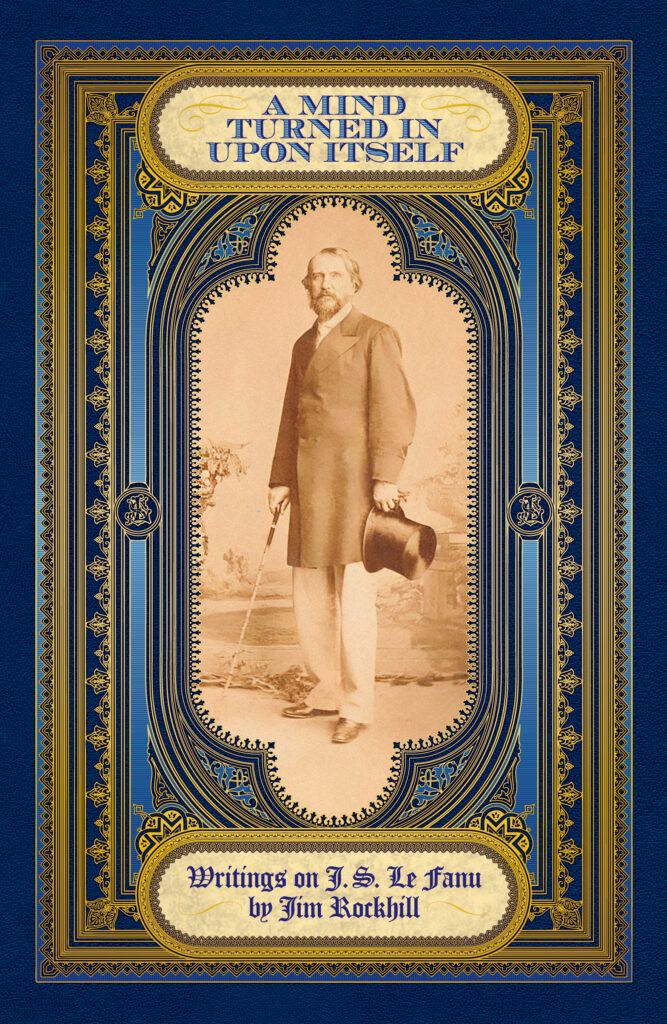

Cover art by John Coulthart

ISBN: 978-1-78380-056-8 (hbk)

Contents

A Word to the Reader

A Mind Turned in Upon Itself

I. As on a Darkling Plain (1814-1861)

II. A Mind Turned in Upon Itself (1862-1870)

III. A Dream of Shadow and Smoke (1870-1873)

The Faux and the Spurious: False Ghosts and Doubtful Le Fanu

Paths of “The Watcher”

Textual Issues in “Ghost Stories of the Tiled House”

Aunt Margaret’s Terribly Strange Bedfellow

Exterior Visions: Assessments of “Green Tea” by Le Fanu’s Contemporaries

“A Little Rift Within the Lute”: Le Fanu’s Loved and Lost

Lovecraft’s Response to the Work of Le Fanu

Works Cited

Sources

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Jim Rockhill

Jim Rockhill has edited volumes collecting Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Bob Leman, and E.T.A. Hoffmann; he is also the co-editor of Jane Rice’s collected fiction, the essay collection Reflections in a Glass Darkly, and the anthology Dreams of Shadow and Smoke; and has contributed essays and reviews to Supernatural Literature of the World, The Freedom of Fantastic Things, Warnings to the Curious, The Green Book, Dead Reckonings, and a variety of other encyclopaedias and journals.

Read more“Essential for anyone who loves the works of Sheridan Le Fanu . . . an absorbing read, a book to dip into and come back to.” – Supernatural Tales

“In A Mind Turned in Upon Itself, Jim Rockhill abundantly demonstrates his love and appreciation for J. S. Le Fanu’s fiction and presents such an enthusiastic examination of the work as to inspire people to seek out whatever of that work they have not so far read. Highly recommended.” – You’re Reading

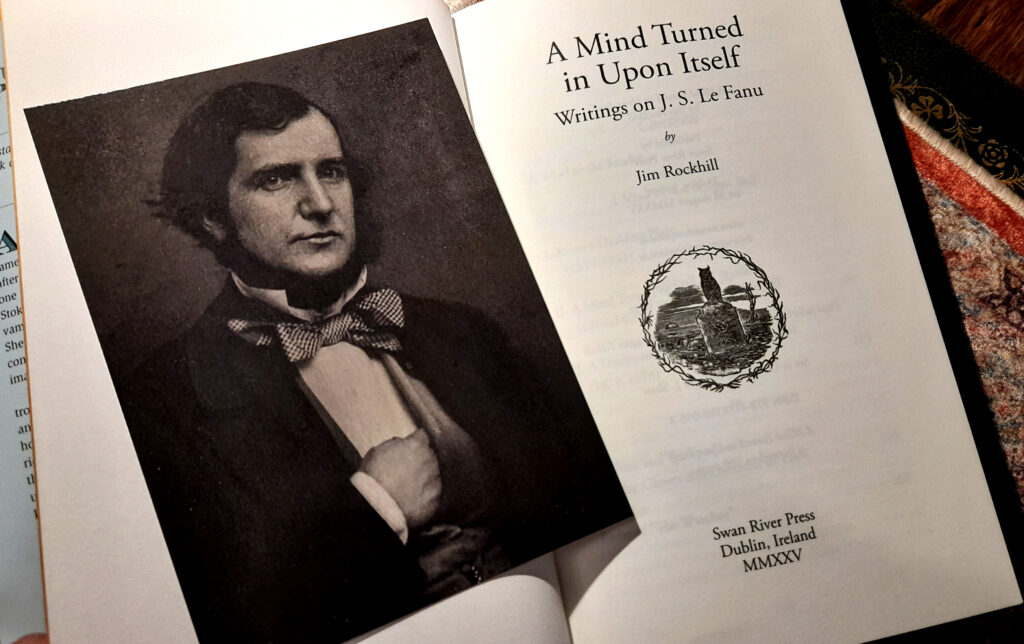

A Mind Turned in Upon Itself: Writings on J. S. Le Fanu by Jim Rockhill; cover design by John Coulthart; cover production by Meggan Kehrli; edited by Brian J. Showers and Helen Grant; copyedited by John Kenny; typeset by Steve J. Shaw; published by Swan River Press at Æon House.

First Hardback Edition: Published on 28 August 2025; limited to 350 copies, the first 100 of which are embossed and hand-numbered; dust jacketed; illustrated cloth-printed boards; endpapers (Wibalin Old Gold WBN507); xii + 237 pages; lithographically printed on 80 gsm cream paper; sewn binding; head- and tail-bands (Winterband 441 gold); issued with one postcard; printed by CPI Antony Rowe; ISBN: 978-1-78380-056-8.

“Dreaming of Shadows and Smoke”

“Dreaming of Shadows and Smoke”

A Talk with Jim Rockhill

Conducted by John Kenny, June 2025

Jim Rockhill has edited collections of fiction by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Bob Leman, and E.T.A. Hoffmann; he is also the co-editor of Jane Dixon Rice’s collected fiction, the essay collection Reflections in a Glass Darkly, and the anthology Dreams of Shadow and Smoke; and has contributed essays and reviews to Supernatural Literature of the World, The Freedom of Fantastic Things, Warnings to the Curious, The Green Book, Dead Reckonings, and a variety of other encyclopaedias and journals.

John Kenny: When did you first encounter Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s work and what impact did it have on you?

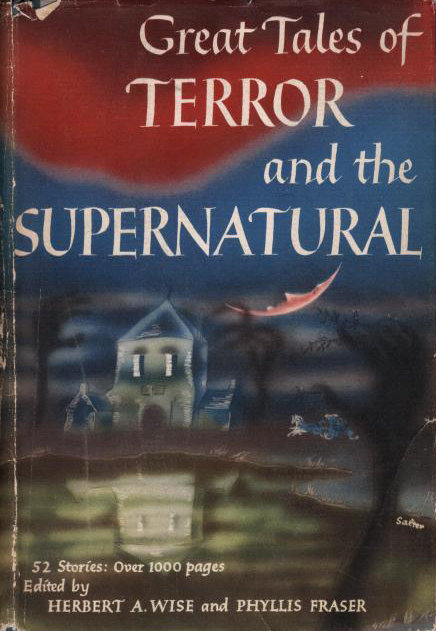

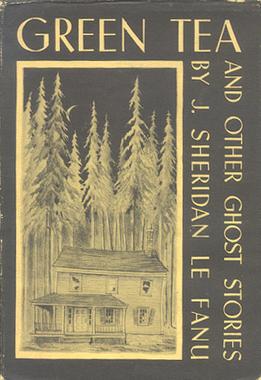

Jim Rockhill: I first encountered Le Fanu through Wise and Fraser’s Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, which I had received as a Christmas present at about the age of eleven. I had not been reading the book cover-to-cover, but choosing stories based on how much reading time I had and how interesting the editors’ description made them sound. Having reached the innocuously-titled “Green Tea” on a pleasant afternoon while visiting my grandparents, I was shocked at the world the story depicted. Here was a man, a clergyman no less, plagued by an infernal creature simply because they had suddenly become cognizant of one another’s presence. The thought that an entire world of spirits walked beside us every day unseen, which might notice us with malicious intent at any moment, terrified me on a more fundamental level than anything else I had read in the book.

JK: I’m assuming at least some of the other stories in that anthology were written by contemporaries of Le Fanu’s. What qualities do you think marked him out from the others writing at that time?

JK: I’m assuming at least some of the other stories in that anthology were written by contemporaries of Le Fanu’s. What qualities do you think marked him out from the others writing at that time?

JR: As M. R. James noted, “It is partly, I think, owing to the very skillful use of a crescendo, so to speak. The gradual removal of one safeguard after another, the victim’s dim forebodings of what is to happen gradually growing clearer; these are the processes which generally increase the strain of excitement.” His use of atmosphere and a certain chiaroscuro in limning his scenes is also exceptional. Too many of Le Fanu’s contemporaries relied upon a plot in which the ghost appears merely to ensure its body is found for proper burial and its murderer brought to justice. On the rare occasions when Le Fanu does employ elements of such a plot, he turns them inside out as in “An Authentic Narrative of a Haunted House” and “Madam Crowl’s Ghost”. In the first of these, one or more restless spirits reveal that something terrible happened in the house, but although relics of a death are discovered, we are never told what, why, or even when this occurred. In the second story, rather than seeing the victim calling for vengeance from beyond the grave, it is the guilty spirit of the grotesque Madam Crowl who reveals the crime.

This guilt is a key element in Le Fanu, and is often forced upon characters. It might have a personal source (“The Familiar”, “The Evil Guest”, “Squire Toby’s Will”, “Mr. Justice Harbottle”), but also have been lying in wait within the family’s history (“Ultor de Lacy” and “The Haunted Baronet”) or may even have an ontological source barely understood by the victim of the haunting (“Green Tea”). And this brings up the matter of “mechanism” in many of his stories—“the enormous machinery of hell” that not only draws in the Reverend Jennings (“Green Tea”), but generates the elaborate variety of supernatural events that occur in many of the titles I have listed. I believe Swedenborg’s cosmology affected not only those works of Le Fanu like Uncle Silas and “Green Tea”, where it is quoted directly, but many of his other supernatural works as well.

His creative use of folklore as a foundational, but protean element, rather than a merely cosmetic one, is another point that separates him from most of his contemporaries, anticipating Arthur Machen and inspiring M. R. James.

His creative use of folklore as a foundational, but protean element, rather than a merely cosmetic one, is another point that separates him from most of his contemporaries, anticipating Arthur Machen and inspiring M. R. James.

JK: In A Mind Turned in Upon Itself, you highlight Swedenborg’s philosophical investigations as a key influence on Le Fanu’s work. Do you think that may have been because Swedenborg seems to have had a major impact on Victorian sensibilities in general?

JR: Yes, I think so. We see his first significant cultural impact in the Romantic era with William Blake, but he also influenced not only Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Butler Yeats, but also writers in other languages such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Honoré de Balzac, Charles Baudelaire, and August Strindberg. There is even a brilliant supernatural novella based on Swedenborgian concepts by the late A. S. Byatt titled “The Conjugial Angel”. In this story, Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s sister is haunted by a being that turns out to be the angel formed by the perfect union of male and female after marriage, left hideously incomplete by the death of her fiancé, Arthur Henry Hallam, whose death also inspired Tennyson’s In Memoriam.

JK: You also mention Le Fanu’s creative use of folklore in his work. What kind of access would he have had to this wellspring of mythic tradition?

JR: Joseph and his brother William roamed far and wide during their time in Co. Limerick while their father was Dean of Emly and Rector of Abington, and became well-known as experts not only in the area’s geography, but also its folklore. Years after Samuel Carter Hall and his wife Anna Maria Hall published their three-volume, profusely illustrated guidebook to Ireland, Samuel Carter Hall wrote in his memoirs:

“I knew the brothers Joseph and William Le Fanu when they were youths at Castle Connell, on the Shannon . . . They were my guides throughout the beautiful district around Castle Connell, and I found them full of anecdote and antiquarian lore, with thorough knowledge of Irish peculiarities. They aided us largely in the preparation of our book, Ireland: Its Scenery and Character.”

“I knew the brothers Joseph and William Le Fanu when they were youths at Castle Connell, on the Shannon . . . They were my guides throughout the beautiful district around Castle Connell, and I found them full of anecdote and antiquarian lore, with thorough knowledge of Irish peculiarities. They aided us largely in the preparation of our book, Ireland: Its Scenery and Character.”

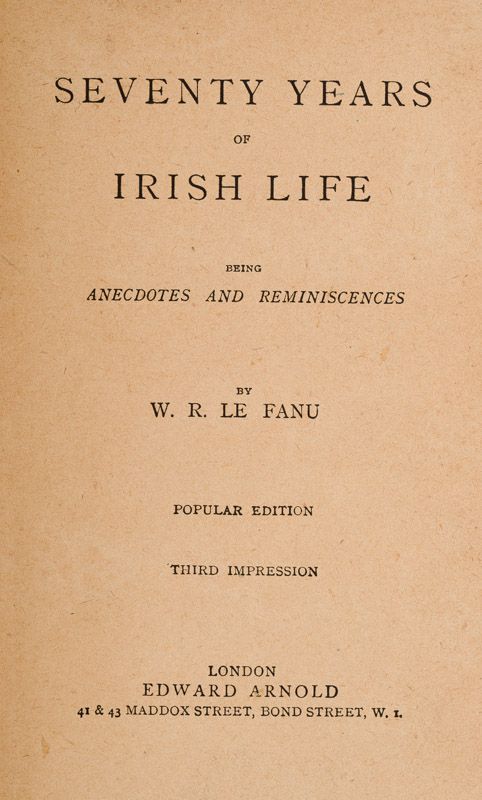

You see further evidence of folkways in Co. Limerick and other areas of Ireland in both Joseph’s fiction and William’s memoir Seventy Years of Irish Life.

JK: Le Fanu clearly loved Ireland and was sympathetic to the plight of the Irish peasantry. But he was also very much in favour of a continued union with Britain. I wonder if the tension caused by this dichotomy found its way into his fiction?

JR: Le Fanu’s maternal grandfather had been confessor to at least one of the rebels executed following the rebellion of 1798, and his mother regaled her children with tales about the nobility of that lost cause and its leaders; but his own position, as with the Protestant Ascendancy in general, was thought to depend upon preservation of the Union with England. Thus, his journalism is strictly pro-Unionist, and his verse is split between poems that are sympathetic to the Catholic Irish population, such as those in “Scraps of Hibernian Ballads” and “Shamus O’Brien” (some of which even regard participants in the rebellion of 1798 heroically) and the tub-thumping Union do-or-die ballads published collectively as “Songs of the True Blue”. His first two novels, The Cock and Anchor and Torlogh O’Brien depict Catholics and Protestants attempting, if not always succeeding, in living together harmoniously, and shorter works including the stories later collected into the Purcell Papers and “Ultor de Lacy” feature Catholics as sympathetic central characters.

JK: I note that Le Fanu rewrote several short stories, and even a novel or two, in the latter years of his life. Do you think this was because of financial necessity, the need to keep a regular supply of work hitting the market, or was he dissatisfied with the original versions?

JK: I note that Le Fanu rewrote several short stories, and even a novel or two, in the latter years of his life. Do you think this was because of financial necessity, the need to keep a regular supply of work hitting the market, or was he dissatisfied with the original versions?

JR: I believe it may have been financial necessity in some cases, but we also see him finding new, more expressive ways to use the material, and you see this throughout his career.

He certainly revised his first novel, The Cock and Anchor of 1845 as his last, Morley Court, published the year he died, but he tinkered with “The Watcher” from its first appearance in 1847, its slight revision for Ghost Stories and Tales of Mystery in 1851, and its final appearance with a series Prologue as “The Familiar” in 1872.

His revision of “Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter” (May 1839) as “Schalken the Painter” (1851) occurred fairly early and retained most of the original text, with a new opening and the removal of some garish details from the Minheer’s appearance.

Other reworkings are much more extensive, and involve considerable elaboration; thus “The Murdered Cousin” of 1851 becomes the triple-decker novel Uncle Silas of 1864, and he keeps re-examining what the events in “Some Account of the Latter Days of the Hon. Richard Marston, of Dunoran” (1848) mean, first in the slightly different “The Evil Guest” in Ghost Stories and Tales of Mystery (1851) and finally in the triple-decker novel A Lost Name, serialized between 1867 and 1868.

The metamorphosis of Le Fanu’s second published story, “The Fortunes of Sir Robert Ardagh” (1838), is a particularly fascinating case, because following the statement “So says tradition”, he begins the story anew with a second interpretation of events:

This story, as I have mentioned, was current among the dealers in such lore; but the principal facts are so dissimilar in all but the name of the principal person mentioned . . . and the fact that his death was accompanied with circumstances of extraordinary mystery, that the two narratives are totally irreconcilable, (even allowing the utmost for the exaggerating influence of tradition), except by supposing report to have combined and blended together the fabulous histories of several distinct heroes . . .

This story, as I have mentioned, was current among the dealers in such lore; but the principal facts are so dissimilar in all but the name of the principal person mentioned . . . and the fact that his death was accompanied with circumstances of extraordinary mystery, that the two narratives are totally irreconcilable, (even allowing the utmost for the exaggerating influence of tradition), except by supposing report to have combined and blended together the fabulous histories of several distinct heroes . . .

When he revisits the theme more than thirty years later in the short novel “The Haunted Baronet” (1870), he enriches the story with deepened characterization and a wide variety of interrelated supernatural and onomastic elements. The two versions of the Faustian tale encountered in the first version assumes the weight of mythology in the second.

JK: Le Fanu’s own death seems to have gathered its share of extraordinary mystery. In fact, the generally accepted account reads almost like a story he would have written. Is it possible at this stage to separate fact from fiction?

JR: There now happens to be evidence supporting both versions of Le Fanu’s death, though the contradictions remain unresolved. S. M. Ellis’s famous account, a version of which was first printed in 1916, makes Le Fanu’s final moments sound like the fate of one of his own Gothic protagonists:

But he was not permitted to have this peaceful passing. Horrible dreams troubled him to the last, one of the most recurrent and persistent being a vision of a vast and direly foreboding old mansion (such as he had so often depicted in his romances), in a state of ruin and threatening imminently to fall upon and crush the dreamer rooted to the spot. So painful was this repeated horror that he would struggle and cry out in his sleep. He mentioned this trouble to his doctor. When the end came, and the doctor stood by the bedside of Le Fanu and looked in the terror-stricken eyes of the dead man, he said: “I feared this—that house fell at last.”

I think Le Fanu might have been proud of that, had he written it himself; however, it came into doubt when William Mc Cormack quoted a letter written by Le Fanu’s younger daughter, Emma, only two days after the event, in which she states:

I think Le Fanu might have been proud of that, had he written it himself; however, it came into doubt when William Mc Cormack quoted a letter written by Le Fanu’s younger daughter, Emma, only two days after the event, in which she states:

. . . he sank very quickly & died in his sleep. His face looks so happy with a beautiful smile on it.

The plaster mask of Le Fanu at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, if it is a death mask, and not one taken earlier, also seems to support Emma’s account. However, Gavin Selerie discovered a monograph written by Edmund Downey in 1910, based on information given him directly and in letters from the author’s elder daughter, Eleanor, and youngest son, Brinsley, which offers an account less dramatic, but otherwise very close to Ellis’s:

Especially did he dream of a vast crazy old mansion ever tottering to its fall, and when the full horror of the dream was upon him he would struggle in his sleep, and sometimes it was deemed necessary to awake him rudely. I have been told that when the doctor was summoned for the last time to the bedside of Sheridan Le Fanu he looked at the face of the dead man and said: “I feared this—that house fell at last.”

How do we reconcile these? Did Emma, at least when setting down what occurred on paper for another person, succumb to wishful thinking? In that case, was the plaster mask a life mask, rather than a death mask? Other specimens of life masks have survived. Or did the memories of Eleanor and Brinsley exaggerate what happened over the intervening decades? We will probably never know.

JK: What are your personal favourites of Le Fanu’s work and what is it about them that work for you?

JR: I am glad that you asked for my favourites, because it is impossible for me to choose only one. “Green Tea” was the first story of his I read, and the impact, as I mentioned earlier, was tremendous. It shook the ground beneath this lapsed Catholic’s feet. I also love both “Ultor de Lacy” and “The Haunted Baronet” for the elaborateness of their supernatural phenomena and the beautiful description of settings and events behind the horror in these and “The Child that Went with the Fairies”. “Carmilla” has been adapted to death, and would seem to be overly familiar, but the story and Carmilla herself are much richer than most of her adaptaters would suggest.

JR: I am glad that you asked for my favourites, because it is impossible for me to choose only one. “Green Tea” was the first story of his I read, and the impact, as I mentioned earlier, was tremendous. It shook the ground beneath this lapsed Catholic’s feet. I also love both “Ultor de Lacy” and “The Haunted Baronet” for the elaborateness of their supernatural phenomena and the beautiful description of settings and events behind the horror in these and “The Child that Went with the Fairies”. “Carmilla” has been adapted to death, and would seem to be overly familiar, but the story and Carmilla herself are much richer than most of her adaptaters would suggest.

JK: Le Fanu’s work lives on, of course, in continued reprintings of his novels and short stories, but he has also been a very definite influence on or inspiration to many other writers. You’ve mentioned M. R. James’ admiration of Le Fanu’s work earlier. Who else do you think has been influenced or inspired by his fiction?

JR: The most famous influence Le Fanu had on another writer appears to be James Joyce, who alludes to The House by the Churchyard in Finnegans Wake. Le Fanu’s novella “A Chapter in the History of a Tyrone Family” (1839) also seems to have anticipated the mad woman in the attic in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) prior to his own expansion of the motif in The Wyvern Mystery twenty-two years later. In an excised chapter from Dracula, published posthumously as “Dracula’s Guest”, Bram Stoker brings the reader to the tomb of a Countess in Styria, which appears to have been inspired by “Carmilla”, and his short story “The Judge’s House” (1891) incorporates many elements from Le Fanu’s “An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in an Old House in Aungier Street” (1853). E. F. Benson, Henry James, and V. S. Pritchett all wrote admiringly of Le Fanu’s work, but if their own ghost stories bear any resemblance to his it is merely in learning from him how to manage a crescendo and following the precept first acknowledged by M. R. James to introduce:

the actors in a placid way; . . . see them going about their ordinary business, undisturbed by forebodings, pleased with their surroundings; and into this calm environment let the ominous thing put out its head, unobtrusively at first, and then more insistently, until it holds the stage.

Marjorie Bowen turns elements borrowed from Uncle Silas to her own account in the poignant short story “A Plaster Saint” (1933), and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film Vampyr (1932) was inspired by the entire collection In a Glass Darkly, rather than any one story, with the memorable scene of the protagonist being carried conscious but incapable of movement deriving from the only non-supernatural story, “The Room in the Dragon Volant”.

Marjorie Bowen turns elements borrowed from Uncle Silas to her own account in the poignant short story “A Plaster Saint” (1933), and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film Vampyr (1932) was inspired by the entire collection In a Glass Darkly, rather than any one story, with the memorable scene of the protagonist being carried conscious but incapable of movement deriving from the only non-supernatural story, “The Room in the Dragon Volant”.

Most of the other identifiable influences spring from “Green Tea”. A German writer, O. C. Recht, produced a translation and “sequel” to the story in 1942. [see The Green Book 25 – Ed.] And there are many haunting animals that nod in the direction of the Reverend Jennings’ simian persecutor, including the hyaena in H. R. Wakefield’s “Death of a Poacher” (1935), Gerald Heard’s “The Cat ‘I Am’” (1944) and The Black Fox (1950), the twisted apish familiar just beginning to speak at the end of Ramsey Campbell’s “The Trick” (1976), the shining bottle caps associated with the ghost in the same author’s “Macintosh Willy” (1977), the otherworldly persecutors in Terry Lamsley’s “Walking the Dog” (1996), some of the stages leading up to the appearance of A. S. Byatt’s “The Conjugial Angel” (1992), and the mischievous monkeys emerging at intervals in both Mike Mignola’s Hellboy and television’s Family Guy.

“The Watcher” also doubtlessly spawned a significant number of stories, though these are less easy to identify, and have been filtered down to our time to the point that direct influence is probably no longer possible. For instance, although they also owe a debt to Lafcadio Hearn’s Japanese tale “The Mujina” (1904), the persecutory aspect and culminating structure in Cynthia Asquith’s “The Follower” (1935) and Stephen King’s “The Boogeyman” (1973) clearly point back to Le Fanu’s tale.

“The Watcher” also doubtlessly spawned a significant number of stories, though these are less easy to identify, and have been filtered down to our time to the point that direct influence is probably no longer possible. For instance, although they also owe a debt to Lafcadio Hearn’s Japanese tale “The Mujina” (1904), the persecutory aspect and culminating structure in Cynthia Asquith’s “The Follower” (1935) and Stephen King’s “The Boogeyman” (1973) clearly point back to Le Fanu’s tale.

And, of course, there are the numerous contemporary writers who contributed to the anthology Dreams of Shadow and Smoke, which Brian J. Showers and I edited for the bicentenary of Le Fanu’s birth.

JK: Finally, I understand you will be visiting Dublin when A Mind Turned in Upon Itself is officially released. What is it about Dublin that resonates with you? And will you be visiting Le Fanu’s grave in Mount Jerome Cemetery?

JR: This will be my fourth visit. Ireland is a wonderful country, with a rich history, particularly Dublin, which feels like a long-lost home to me. The family has wanted to visit Ireland together for years, and want to visit several areas of the country, which will be new to me as well. During the days I will remain in Dublin after the rest of my family returns to the United States, I expect to visit Le Fanu’s grave again and spend time with friends I have not seen since 2014 (thank goodness for the internet for helping to bridge the gap during the interim).